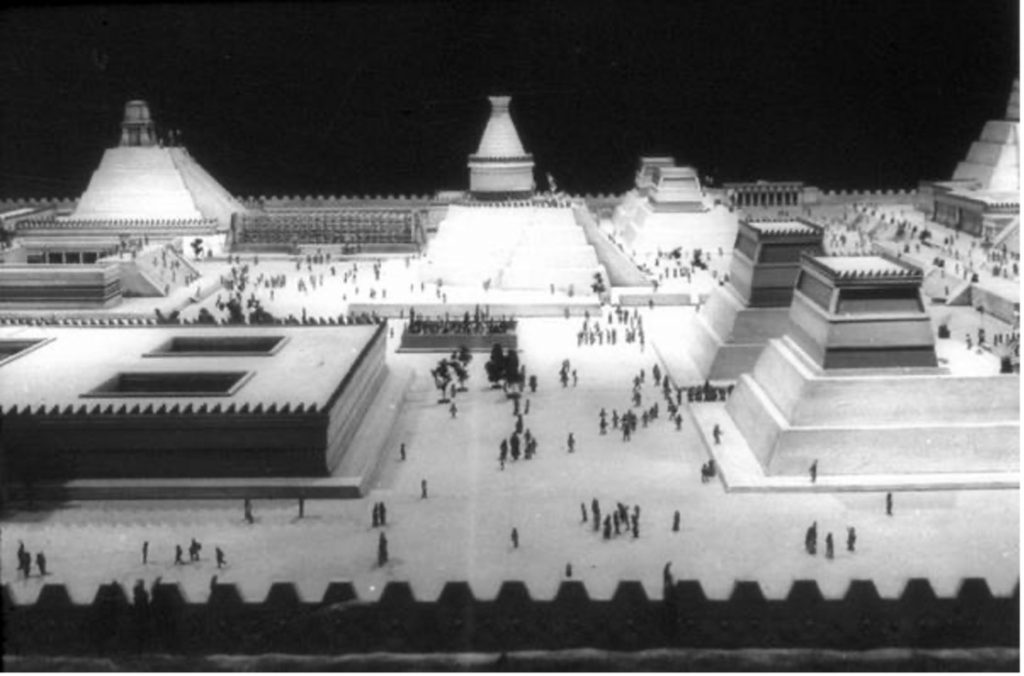

Many have heard of the indigenous Aztec empire and its power over most of central Mexico. Most people know of their pyramids or the gory stories of human sacrifice. However, not all know where these people came from or how their empire began. The origin story for the capital city of the Aztec empire, Tenochtitlan, gives insight into who the Aztecs were and from where they originated. At the time of its birth in 1325, Tenochtitlan was on an island centered in the middle of the Mexican valley. It is said to have had an estimated population of 200,000 during its peak years before its conquest.1 Tenochtitlan was so impressive in size to Spanish conquistadors that it was compared to ancient and medieval European cities like Paris, Naples, and Rome. Colonization by the Spaniards eventually brought genocide, political destruction, and erasure. In addition, the native name Tenochtitlan, coming from the Nahuatl language, was also changed.2 Today, we know this city as the Mexican capital of Mexico City.

The story of the Aztecs and the rise of Tenochtitlan begins before this group of people were even identified as Mexica. Their origins begin with an indigenous group in the land of Aztlan. With the hierarchy of this indigenous group, shamans or priests dominated social power, often leading the group and making big decisions. This social class was referred to as Pipiltin, which consisted of priests, warriors, and government leaders. Not only did priests guide worship and their religion, but they were also in charge of the development of knowledge. This meant priests played direct roles in forming sciences, calendars, education, and mythology. Priests and shamans even served as political/government advisers.3 So, it is evident the power that religious and mythological beliefs had among the people of Aztlan, and later on, among the Aztecs.

This story starts out with leader Tenoch from Aztlan having a vision of the deity Huitzilopochtli. According to Tenoch, they were commanded by Huitzilopochtli to abandon their home. He and his people were ordered to begin a pilgrimage to find a promised land. Tenoch belonged to another prestigious social class of the indigenous people that settled in Tenochtitlan known as the Tlatoque. This group of men administered religion, managed the state, planned war, and collected tribute. Leaders of these men were the Tlatoani. Throughout the time of Tenochtitlan, only twelve of these men existed. Tenoch is recognized as the first Tlatoani to guide the group from Aztlan. The indigenous name roughly translates to “prickly pear cactus of stone.”4 So, when Tenoch told the people that their God Huitzilopochtli commanded them to leave and search for a new home, they listened. The indigenous people that left Aztlan were given the new name Mexica by Huitzilopochtli. This new name served as the base for the later name “Mexicans.”5

Huitzilopochtli is known as the Aztec god of war and god of the sun. Sometimes called by the name Mexitli, this deity was deemed the protector of the Mexica people. Inherently as the sun god, Huitzilopochtli was the recurring winner that triumphed against the dark nights. As mentioned before, this is the deity that served as the driving force for the pilgrimage of the Aztecs.6 This deity played a major role in the lives of the Aztecs and played a crucial role in the foundation of Tenochtitlan, as will be made clear.

Aside from being given the new name, the people from Aztlan were bestowed three gifts that would guide and define their new way of life. Huitzilopochtli was said to have given the Mexicas the arrow, the bow, and the net. With these new tools, they were able to fight and hunt, ensuring their survival throughout their journey. As their pilgrimage in search of a new home continued, they honed their skills as military strategists, fishermen, and farmers.7 Each of these tools and skills would also show up in the great city of Tenochtitlan. Things seemed to start off perfect and without question. However, no one knew how long the journey would take. Was it going to be months, years, or centuries? They wondered how they would know they had arrived at the promised land.

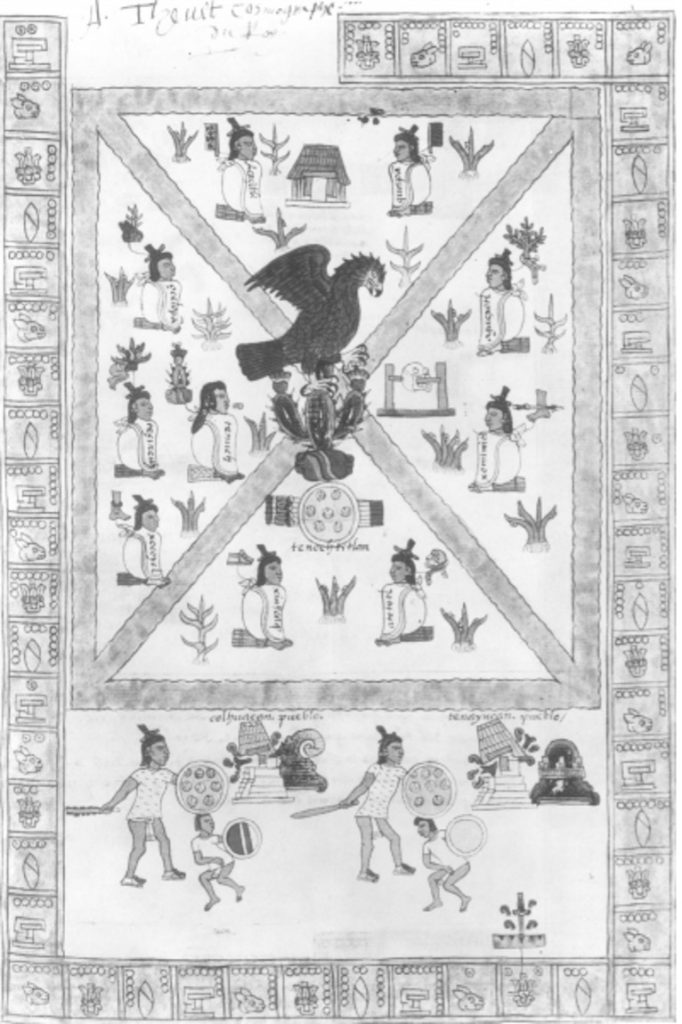

Their long journey had a defining moment when they encountered Coatepetl, also known as the serpent mountain. Although they were far from their soon-to-be Tenochtitlan, the Mexica settled. Getting comfortable, they built a home that resembled Aztlan and served as a blueprint for Tenochtitlan. This temporary home was built to reach out in each direction of the universe: north, west, east, and south. The Mexica people even built a dam to create a lagoon teeming with life, allowing them to survive off the vegetation and fish. Despite their efforts to build a home, this was not the promised land that Huitzilopochtli had spoken of. The sun god and devout followers knew they had to keep moving to find their new home. It is said that this led to a conflict between followers of Huitzilopochtli and those who were following a woman warrior named Coyolxuahqui. She and her followers refused to keep moving. As the two groups feuded and became hostile, the followers of Huitzilopochtli attacked and sacrificed Coyolxuahqui.8 This meant that the rest of the Mexica people who continued the journey were either devout followers of the sun god or knew better than to object.

This defining moment for the Mexica pilgrimage has been depicted in historical sculpture and indigenous texts. This part of the story represents two political groups fighting for power. In Aztec history, this moment is known as a celestial battle between the sun and the moon, where Huitzilopochtli (the sun god) is victorious. In some stories or other variations, this battle is represented by a solar eclipse.9

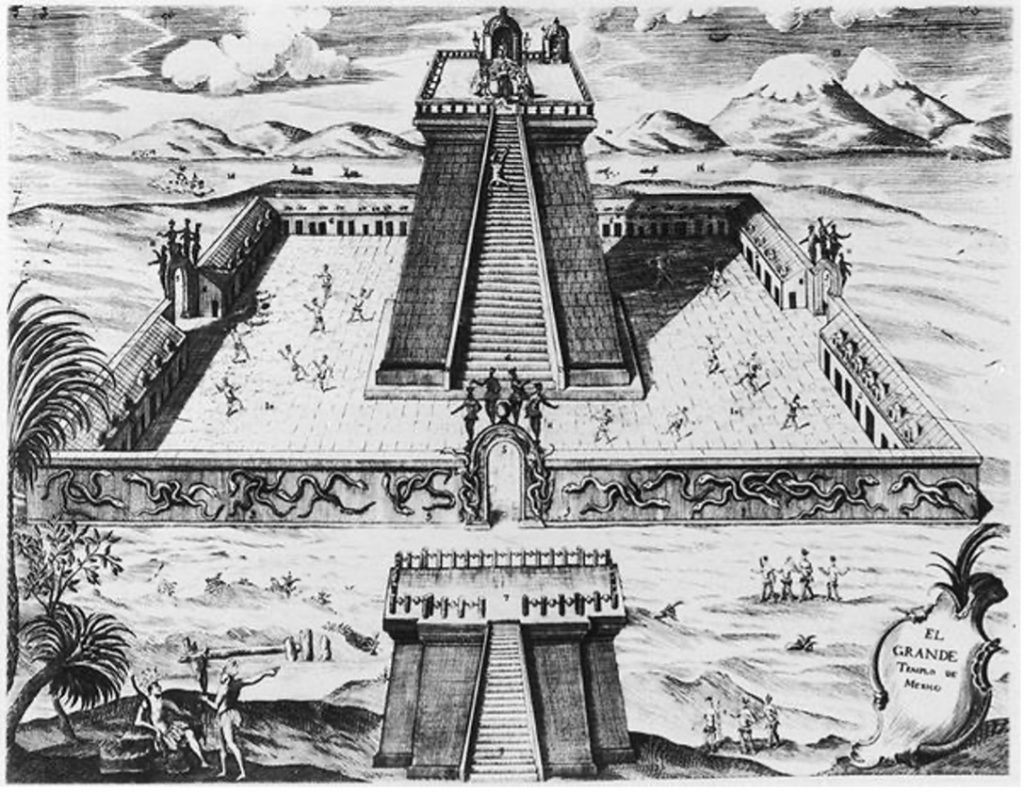

After setting the example, they were able to continue their journey to the promised land. Tired yet eager to please their god, the Mexicas finally received a sign from Huitzilopochtli that they were at their new home. It is said that Tenoch and his tribe spotted a mighty eagle on top of a prickly pear cactus devouring a snake out on lake Tezcoco.10 This was the official sign that they had arrived. That same spot would be where the first temple to Huitzilopochtli was built. This would later be known as the famous Templo Mayor. The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, would be built as a floating city on an island in the middle of the lake reaching out to the north, west, east, and south directions of the universe.

That is the story of how Tenochtitlan came to be. This is a story that has survived centuries. It is a mix of history and indigenous mythology. It is amazing that this origin story has been able to survive time, conquest, and colonization. Today, we can even see the eagle devouring the snake on the Mexican flag. The capital of Mexico is what used to be Tenochtitlan. Mexico City’s Metropolitan Cathedral is built over Tenochtitlan’s Templo Mayor. With different variations in some of the details of the story, it is up to readers to determine what they believe. One of the biggest struggles for this origin story is trying to identify where Aztlan or their original home was. Some scholars suggest it was near modern-day Guanajuato, Nayarit, or further north in Mexico.11 Whether you believe it is fiction, historical, mythological, or a mixture, it is a story that will continue to live on.

- Los Aztecas y la gran Tenochtitlan. Vol. 9. La manera de conocer el pasado mesoamericano a través de su arte (Mexico D.F.: Fundación Cultural Armella Spitalier, 2008), 3. ↵

- Barbara Mundy, The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2015), 1. ↵

- Los Aztecas y la gran Tenochtitlan. Vol. 9. La manera de conocer el pasado mesoamericano a través de su arte (Mexico D.F.: Fundación Cultural Armella Spitalier, 2008), 18-20. ↵

- Los Aztecas y la gran Tenochtitlan. Vol. 9. La manera de conocer el pasado mesoamericano a través de su arte (Mexico D.F.: Fundación Cultural Armella Spitalier, 2008), 4, 19. ↵

- David Carrasco, The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction. Vol. 296. Very Short Introductions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 18. ↵

- Los Aztecas y la gran Tenochtitlan. Vol. 9. La manera de conocer el pasado mesoamericano a través de su arte (Mexico D.F.: Fundación Cultural Armella Spitalier, 2008), 8. ↵

- David Carrasco, The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction. Vol. 296. Very Short Introductions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 18-19. ↵

- David Carrasco, The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction. Vol. 296. Very Short Introductions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 19. ↵

- David Carrasco, The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction. Vol. 296. Very Short Introductions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 19. ↵

- Barbara Mundy, The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2015); Los Aztecas y la gran Tenochtitlan. Vol. 9. La manera de conocer el pasado mesoamericano a través de su arte (Mexico D.F.: Fundación Cultural Armella Spitalier, 2008), 4. ↵

- Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, Tenochtitlan (México, D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2006), 23. ↵

3 comments

Helena Griffith

What a fascinating article, especially for a Latino whose nation shares a lot of cultural similarities with Mexico. Before reading your well-written post, I really had no idea what this subject was about. The sources you cited were incredibly solid and reliable, which contributed to the credibility of your post. Additionally, you employed some excellent graphics that aided my reading. Overall, I think you did a great job.

Mauricio Rebaza Figueroa

Excellent article! What a really interesting article, especially reading it as a latino whose country shares a lot of culture with Mexico. I really had no clue about this topic before reading your well-written article. The sources you used were really good and strong to help with the trust-worthiness of your article. You also used used really good images that helped me while reading. Overall, you did a really good job.

Carlos Hinojosa

What always got me thinking is that what if the Americas had the exact same resources as the rest of the World? How different would they be? Would they still have been easily dominated or would they have equals or even superiors to their European counterparts. I personally believe that if the Americas had that access the course of history would be completely different. I don’t know how their culture would be, but it would be interesting. A very good article.