Introduction

As technology has become increasingly essential to the average person’s day-to-day life, it is important to understand some of the consequences of some of these technological instruments. One technological device that has become gradually dangerous in daily routines is personal audio devices. Headphones are increasingly being used in the gym, libraries, and many other day-to-day activities. These devices are used so much they are now even used as a fashion accessories and are essential to relaxation periods.1 We are now discovering the effects of daily excessive noise and how damaging unsafe usage can become. This issue is mainly targeting the youth, and it is only in time we see the rippling effects that come with this device.

How we hear

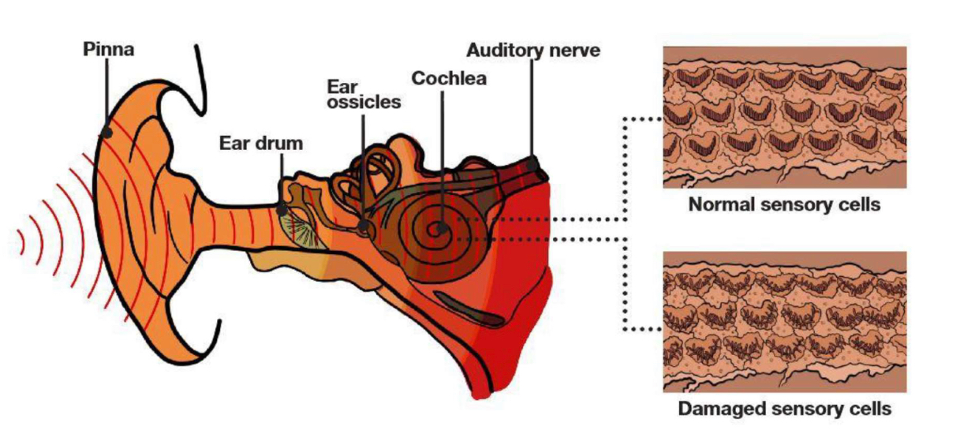

The ear is part of the body that allows the brain to understand the noise from the environment around us. Hearing is our perception of the energy carried by sound waves. Sound is how the brain interprets the frequency, amplitude, and duration of what we are hearing. Sound waves begin by striking the tympanic membrane which creates vibrations in the ear. Wave energy is then passed through three bones of the middle ear called the malleus, incus, and stapes which vibrate. Stapes is connected to the membrane of the oval window. In the oval window, vibrations create fluid waves that travel within the cochlea. These fluid waves push on the flexible membranes of the cochlear duct. Hair cells then bend, and ion channels open. This then makes an electrical signal that creates a neurotransmitter release. A release of the neurotransmitter onto sensory neurons generates action potentials that travel through the cochlear nerves to the brain. The energy travels across the cochlear duct into the tympanic duct and back into the middle ear at the round window. This process is how auditory information can be transcribed to the brain through nerve electrical impulses.2

How hearing loss occurs

There are three forms of hearing loss: conductive, central, and sensorineural. The damage to the structures of the inner ear, including the death of hair cells as a result of loud noises such as those created by personal audio devices, is an example of sensorineural hearing loss. One thing that is crucial to understand about the ear is that the number of hair cells that make up the ear is fixed and present at birth. This means that once they have been damaged, they cannot be regenerated.3 This specific type of sensorineural hearing loss through hair cell damage mainly occurs due to excessive exposure to loud sounds. In the United States, roughly 15% (26 million) of people between the ages of 20 to 69 years have high-frequency hearing loss from overexposure to loud noise at work or during leisure activities.4 This can be caused by long-term repeated exposure to loud volumes or short-term intense sounds. It is then characterized by the combination of intensity, duration, and frequency. Presently OSHA mandates that levels do not exceed 90 dB for eight hours, and for each 5 dB above the eight hours, standard OSHA recommends halving the exposure time. For example, a worker should not be exposed to 95 dB for more than four hours.3

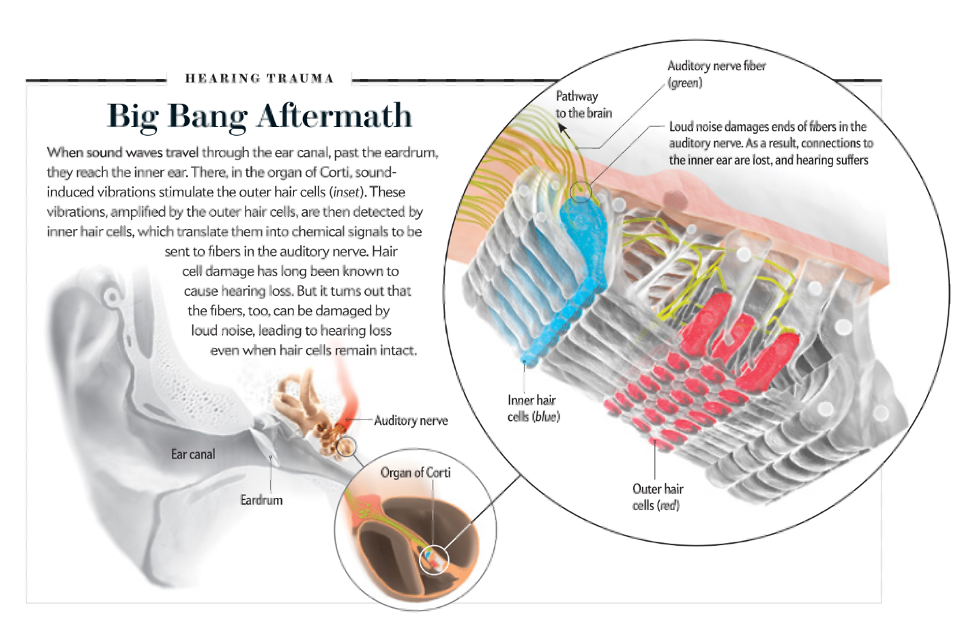

These loud sounds cause immediate and irreversible damage to fibers in the auditory nerve, which is what conveys the sound information to the brain. Tinnitus is the term for the ringing sensation in the ear and is classified as a temporary threshold shift that results in temporary loss of hearing.6 This typically occurs after attending a concert, sporting event, or any other loud environment. Hearing thresholds typically return to normal hours to days after exposure. However, permanent damage could occur with regular noise exposure and damage to the sensory cells. These instances occur in events such as long-term exposure to loud noises, such as in personal audio devices. If these unhealthy listening habits continue for years, this will result in the threshold being raised forever.7 This means the volume of the music, TV, and any other communication must be louder so that the person can hear clearly. This is commonly seen in the elderly when they cup their hands around their ears to hear better due to their hearing thresholds being elevated.

Permanent damage

Frequent exposure to loud sounds causes hair cells to lose their rigidity and their ability to work properly. For the cochlea to work effectively during long periods of loud sound, the hair cells need a high amount of energy. Noise trauma involves an increase in oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS), causing an imbalance in antioxidant defenses. Antioxidants have been demonstrated to protect the cochlea by restoring the redox balance.8 These oxidants are initiators for intracellular cell death signaling.9 By increasing oxygen levels to support the need for high energy, the ear cannot handle the number of free radicals, thus causing apoptosis (cell death).9 Damage to the bundles of stereocilia is irreversible, and once these cells are lost, they can never regenerate. Not only does this affect the hair cells, but as exposure continues can damage the auditory nerve fibers. These nerve fibers are where they form synapses with hair cells. By overstimulating these hair cells, an excess of the signaling molecule glutamine is released, causing swelling and eventual rupture of the terminals. 11

In the lab conducted by M. Charles Lieberman, he tested how damaged synapses could regenerate in the adult ear. With animal studies, he was able to study the relationship between hair cells and auditory nerve fibers. What he found is that the loss of the auditory nerve fibers without the loss of hair cells does not affect the audiogram until the loss is greater than 80 percent. Even so, twenty-five years later, his colleague Sharon G. Kujawa and Lieberman experimented on if young mice could accelerate the onset of age-related hearing loss. The sounds they used were elevated past the threshold for only a temporary period which created no damage to hair cells. However, what they discovered was that from six months to two years later, they saw a cumulating loss of auditory nerve fibers. When the threshold returned to normal, as many as half of the auditory nerve synapses were gone, and this damage was irreversible.3

Early onset hearing loss

This issue is mainly affecting the younger generation as the usage of headphones is becoming more frequent. WHO estimates that 1.1 billion young people could be at risk for hearing loss due to unsafe noise hearing.3 The problem is not so much listening to music at a high volume but listening to it for a long period. This is especially dangerous in earbuds which it is placed inside the ear. When listening to music, if someone else around you can hear the music, this is an indication that it is causing ear damage.14 It is important to listen to music for short durations if the music is going to be at a higher volume. In a study conducted by B Aishwarya Reddy and Thenmozhi M S, where they surveyed 20 college students, they discovered that 59.7% of their students listen to music for more than two hours a day. About 75.6% used headphones to listen to music, and 43.3% of those who did listen to music tended to be in a noisy setting. However, the survey also showed that about 50% of the students are aware of the precautions and prevalence of hearing loss.15

Various long-term difficulties come with noise-induced hearing loss. One effect that comes with noise-induced hearing loss is difficulty communicating with others and distinguishing between speech consonant sounds. Sounds such as “fish” and “fist” would be more difficult to understand with this type of damage. This is especially important to note when looking at its effects on young children where headphones and other personal audio devices are becoming more common in educational practices. Research has shown that in young children, this can impair language acquisition and lead to anxiety, attention-seeking behaviors, and learning disabilities. Children who also listened to loud sounds had lower academic performance and less motivation than those who did not. It has also been found that students who use personal audio devices struggle with self-isolation and communication. This affects the individual’s potential at an early age and increases psychological distress leading adolescents to become less attentive, unsocial, and less active.16 Some schools have taken action and prohibited personal audio devices to promote socialization among students.11

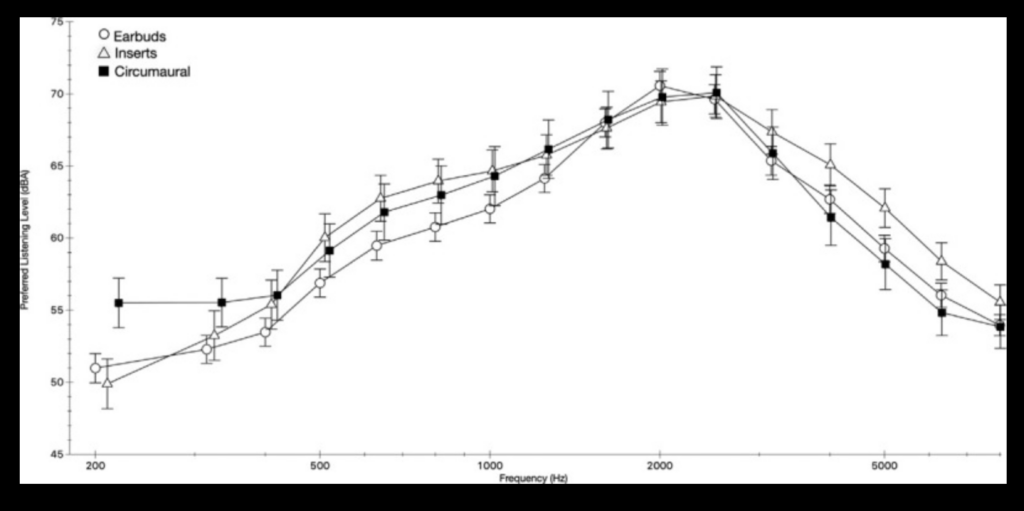

Furthermore, listening to loud sounds has also been connected to the abuse of alcohol and other controlled substances. In a study conducted by John Parsons, Mark B Reed, and Peter Tore at Diego State University they examined the relationship between preferred headphone type, listening levels, and other health risk behaviors. For the experiment, each student got to choose their headphone type and proceeded to listen to music for an hour at their preferred level. What they discovered was that men prefer to listen to music at a higher level than women. Students who had higher drinking activity had louder listening sounds as opposed to those who did not drink. Lastly, students who reported marijuana users also reported higher volume levels when listening to music. 6

Looking ahead

Research has shown that loud noises can be more damaging to the cochlea than natural aging. Noise exposure can also make the ears more susceptible to natural aging hearing loss than others who have not been exposed to higher volumes. Due to limited research on this part of the body, it is unclear if hearing loss is unavoidable with aging or if it is a product of overexposure to loud noises being that they are hard to differentiate. A research study was conducted where researchers gathered groups of people in the Mabaan tribe in the Sudanese desert, which is relatively quiet and has little to no exposure to damaging noises. What they found was that the Mabaan men who were 70-79 years had significantly better hearing than a group of American men of the same age.3

Treatment and prevention

Unfortunately, there has been no cure for noise-induced hearing loss. There currently is a treatment to help reduce destruction, including hyperbaric oxygen therapy, but this has to be treated immediately after exposure to the incident to halt further damage. Antioxidant and pharmacological therapy have been shown to stop damage to sensory cells. However, at the moment, there are no meditative methods available for the reversal of noise-damaged hearing loss. Looking on, there has been a more scientific exploration into gene and stem therapies. 6 It has been hypothesized that we may be able to reverse degradation by treating surviving neurons with growth-promoting fibers that could reconnect inner hair cells.

Although damage created on hair cells is irreversible, there are ways to prevent further harm. It is important to take all the precautions for the safety of ears to ensure that they can be able to function properly going forward. Leslie Nicolau, a physician from the Otorhinolaryngology Service of the Posadas Hospital, recommends that the volume should not exceed more than 50-60% of the total volume and to limit exposure to noises greater than 85 dB. Researchers encourage students to be cautious of the volume and cumulative exposure they are listening to music.11

Avoiding loud sounds will stop the damage from worsening. Nicolau also advises not to be in an environment with different sounds at the same time and to take a 10-minute break per hour the headphones are used.22 It is also important to go to annual checkups and note any difficulties that may be occurring.22 This organ is not only responsible for the sole purpose of hearing but can cause many other irreversible consequences that disrupt the cognitive processes that flow through our brains. It is essential to take all safety measures to keep this irreplaceable organ working properly and fully functional.

- Liberman, M. C. (2015). HIDDEN HEARING LOSS. Scientific American, 313(2), 48–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26046106 ↵

- Purves, D. (2018). Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates ↵

- Liberman, M. C. (2015). HIDDEN HEARING LOSS. Scientific American, 313(2), 48–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26046106 ↵

- Gupta, A., Bakshi, S. S., & Kakkar, R. (2022). Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Hearing Damage Among Adults Using Headphones via Mobile Applications. Cureus, 14(5), e25532. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25532 ↵

- Liberman, M. C. (2015). HIDDEN HEARING LOSS. Scientific American, 313(2), 48–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26046106 ↵

- Parsons, J., Reed, M. B., & Torre Iii, P. (2019). Headphones and other risk factors for hearing in young adults. Noise & health, 21(100), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/nah.NAH_35_19 ↵

- Engdahl, B., & Aarhus, L. (2021). Personal Music Players and Hearing Loss: The HUNT Cohort Study. Trends in hearing, 25, 23312165211015881. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165211015881 ↵

- noise-induced cochlear inflammation – researchgate. (n.d.). Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257200935_Noise-induced_cochlear_inflammation ↵

- Sendowski, I., Holy, X., Raffin, F., & Cazals, Y. (2011). Magnesium and hearing loss. In R. VINK & M. NECHIFOR (Eds.), Magnesium in the Central Nervous System (pp. 145–156). University of Adelaide Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1t3055m.14 ↵

- Sendowski, I., Holy, X., Raffin, F., & Cazals, Y. (2011). Magnesium and hearing loss. In R. VINK & M. NECHIFOR (Eds.), Magnesium in the Central Nervous System (pp. 145–156). University of Adelaide Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1t3055m.14 ↵

- Kris Chesky. (2008). Preventing Music-Induced Hearing Loss. Music Educators Journal, 94(3), 36–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4623689 ↵

- Liberman, M. C. (2015). HIDDEN HEARING LOSS. Scientific American, 313(2), 48–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26046106 ↵

- Liberman, M. C. (2015). HIDDEN HEARING LOSS. Scientific American, 313(2), 48–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26046106 ↵

- Krug, E., Cieza, A., Chadha, S., Sminkey, L., Martinez, R., Stevens, G., White, K., Neumann, K., Olusanya, B., Stringer, P., Kameswaran, M., Vaughan, G., Warick, R., Bohnert, A., Henderson, L., Basanez, I., LeGeoff, M., Fougner, V., Bright, T., & Brown, S. (2016). What causes hearing loss in children? In CHILDHOOD HEARING LOSS: Strategies for prevention and care (pp. 6–8). World Health Organization. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep33171.4 ↵

- AlQahtani, A. S., Alshammari, A. N., Khalifah, E. M., Alnabri, A. A., Aldarwish, H. A., Alshammari, K. F., Alshammari, H. F., & Almudayni, A. M. (2021). Awareness about the relation of noise-induced hearing loss and use of headphones at Hail region. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012), 73, 103113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.103113 ↵

- Gupta, A., Bakshi, S. S., & Kakkar, R. (2022). Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Hearing Damage Among Adults Using Headphones via Mobile Applications. Cureus, 14(5), e25532. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25532 ↵

- Kris Chesky. (2008). Preventing Music-Induced Hearing Loss. Music Educators Journal, 94(3), 36–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4623689 ↵

- Parsons, J., Reed, M. B., & Torre Iii, P. (2019). Headphones and other risk factors for hearing in young adults. Noise & health, 21(100), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/nah.NAH_35_19 ↵

- Liberman, M. C. (2015). HIDDEN HEARING LOSS. Scientific American, 313(2), 48–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26046106 ↵

- Parsons, J., Reed, M. B., & Torre Iii, P. (2019). Headphones and other risk factors for hearing in young adults. Noise & health, 21(100), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/nah.NAH_35_19 ↵

- Kris Chesky. (2008). Preventing Music-Induced Hearing Loss. Music Educators Journal, 94(3), 36–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4623689 ↵

- Use of headphones: rest periods and controls recommended to avoid hearing loss. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.blume.stmarytx.edu/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:67P1-2BH1-JCG7-84T4-00000-00&context=1516831 ↵

- Use of headphones: rest periods and controls recommended to avoid hearing loss. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.blume.stmarytx.edu/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:67P1-2BH1-JCG7-84T4-00000-00&context=1516831 ↵

16 comments

Karicia Gallegos

Congrats on your nomination! This article is very interesting and helpful. I was aware that headphones can harm hearing, but I didn’t know how much. I never sat there while using headphones and consider how it might affect my hearing. I am now more mindful of what it might eventually do to my hearing after reading this article. Overall, wonderful job!

Maximillian Morise

This is a very well thought out article on the issue of hearing loss and how it is increasing throughout our society with the usages of new and advanced earphones and headphones. Congratulations on your nomination!

Osondra Fournier-Colon

I am guilty of blasting my earbuds, especially in the gym, and this article makes me more self-aware of that. I like how you but the biology of the ears to give the reader a better sense of how earbuds can become harmful over time. Also, it is terrific to include the biology of ear loss and what causes it through periods. This is a great article, spreading awareness and educating people on the harm of blasting earbuds.

Jared Sherer

Good job, after reading your article I have learned so much. I actually turned down the volume on my headphones a little bit. I enjoyed reading about hearing and how we could avoid hearing loss at a rapid pace. You did a great job being informative and keeping the reader interested. The article was well written and fun to read. Good job!

Abbey Stiffler

Sara, congrats on your article for being nominated! In contrast to popular belief, headphones have a much greater impact on hearing loss. Everybody uses headphones at least once per day without realizing the harm it does to the head. Although I was already aware of the risks associated with listening to loud music, the article’s excellent facts really helped me grasp the situation.

Karah Renfroe

Congrats on your nomination! This article was very informative and descriptive! I think this article topic is really unique and something I have not considered much previously, however upon reading it it definitely made me think about the issue. I feel like I personally have become less likely to interact as I am walking to class, due to having my AirPods in. Headphones do have the ability to allow you to tune out and thus potentially become less social and interactive. This can have long-term effects on our communication and social skills, in a way that I do not think my generation is realizing. As headphone usage continues I would like to see studies showing more stats and research on this issue!

Isabel Soto

Sandra, this is a very interesting and informative article! I knew that headphones can damage hearing, but never knew to what extent. There is conductive hearing loss, central hearing loss, and sensorineural hearing loss. When using headphones I never sit there and think about any of the effects on my hearing. After reading this article I am now more aware of what it may do to my hearing as time goes on.

Alanna Hernandez

Usually we see studies on the effects on eyes from looking at screens that are too close to our eyes from looking at our phones. it wasn’t until recently that I saw a research paper that the human eyes actually growing longer and that is actually the reason why eyesight is getting worse. I never thought about our other senses also worsening as technology advances but maybe it’s the same thing we’re in five years we realize the human body is just evolving, In a weird way just like our eyes.

Andrea Tapia

Hi Sara, congratulations on getting your article published! Outstanding article on speaking about what headphones and earphones have taken control of people’s lives. It is so easy now to put them on and block out everything that may be happening in the world. A lot of people use them to be able to forget about their problems or even feel the comfort music holds in them. Now people are less aware of their surroundings and have a hard time appreciating nature because of technology.

Nnamdi Onwuzurike

Congratulations on your nomination! This article provides a thought-provoking exploration of what our world might look like if we continue on our current path of environmental destruction and climate change. The author presents a bleak picture of a future where human activity has caused irreparable damage to the planet, resulting in catastrophic consequences for both human civilization and the natural world. The article serves as a powerful call to action, urging readers to take responsibility for the future of our planet and work together to ensure a sustainable and livable world for generations to come.