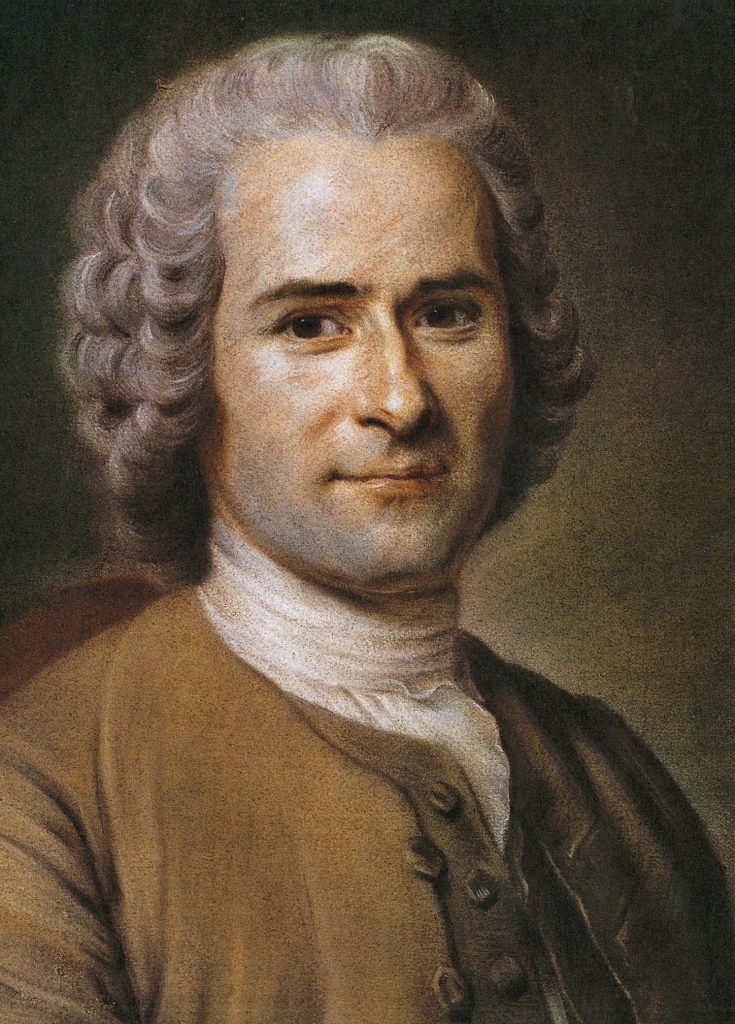

“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” -Jean-Jacques Rousseau1

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in the independent Calvinist city-state of Geneva on June 28, 1712. His mother, Suzanne Bernard, died exactly nine days after his birth, and as a result his father, Isaac Rousseau, was responsible for raising and educating Jean-Jacques, which he did until he was ten years old.2

When Rousseau was ten, his father fled Geneva to avoid imprisonment. Rousseau was left to live with his aunt and uncle. While living there, he acquired a passion for music from his aunt, but no one would have thought that he would ever be able to make a living from music; after all, he was the son of a watchmaker. By thirteen, Rousseau was sent to work as a notary, which did not last long, because again he was only seen as the son of a watchmaker.3 His only option was to work as a watchmaker, so he spent three years of his life there, which in his autobiography, Confessions, he describes as his “miserable years.”4 He spent the next twenty years of his life working in various menial jobs in order to make a living. But then in 1750, when he was thirty-seven years old, his life took a radical turn.

Rousseau wrote music for one of the operas that he composed, Le Devin du village (“The Village Soothsayer”).5 This opera was so successful that it caught the attention of King Louis XV. Many say that Rousseau could have lived an easy life thereafter, but his Calvinist blood would not let him live with that worldly glory.6 When Rousseau was thirty-seven, he had what he called a “terrible flash” (an illumination), that modern progress had corrupted people instead of improving them.7 So, he started writing his first important work, an essay called Discours sur les sciences et les arts, or Discourse on the Sciences and Arts, also known as his First Discourse; and he entered it in a contest at the Dijon Academy of Science in 1750, in which his essay won.8 He had already started writing articles for Diderot’s Encyclopedie, but his Discourse rejected the main idea of the Enlightenment, which was that technology and science would gradually make the world a better place for all of humanity. Rousseau argued that all advances of knowledge were harmful and would take men into further corruption.

Rousseau’s First Discourse surprised everyone; no one would have ever thought that a person who fled his hometown of Geneva with only the shirt on his back would have been able to challenge the intellectual establishment of mid-eighteenth-century Europe. But Rousseau knew that his First Discourse was going to create a storm, with his open hostility to prevailing opinions. He knew that there was not going to be many people that would agree with him, but he felt that it was necessary to challenge civilization itself. This was the start of his fame as one of the most influential but controversial writers in the Enlightenment period. Unlike the rest of the Enlightenment thinkers, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was different. For example, unlike Montesquieu and Voltaire, Rousseau had not received a formal education; instead, he was self-taught. But knowing that he was not as educated as the rest of the Enlightenment thinkers did not stop him from writing what he felt had to be written. He continued to write and to change the way everyone thought in the eighteenth century.

In 1755, Rousseau published his Second Discourse, or Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men. This was a followup to his First Discourse, and it argued many new points, one of them being that the best political system is that of a small city-state in which the body of patriotic citizens is sovereign. In this discourse he also contradicted Thomas Hobbes, an English philosopher. Rousseau stated that Hobbes was wrong in supposing that a natural state of war ever existed among men. He also stated that Hobbes’ “war of all against all” was rather the product of historical development and not a theoretical state of nature among men. Rousseau raised the question of whether or not society itself is good for the human species. He then states that at earlier points in humanity’s natural development, humans were good, but as society developed, human nature became corrupted.9 Rousseau’s Second Discourse did not receive very positive criticism from his fellow Enlightenment thinkers, but there is evidence of letters that were exchanged back and forth between Voltaire and Rousseau, Philopis and Rousseau, and he responded to the observations made by Charles-George LeRoy. In those letters and responses Rousseau defended his point of view with his typical wit.

Another interesting and controversial work of Rousseau’s was The Social Contract (1762), in which he talks about how everyone is born free, but that freedom is taken away when one enters into civil society. He suggests that legitimate authority comes from a social contract agreed upon by all citizens for their mutual preservation. He calls the grouping of all citizens the “sovereign,” and suggests that it should be considered as a person, with a general will. This was by far one of the most controversial but open-minded works by Rousseau.10

Rousseau was one of the most incredible writers and thinkers of his time. He proposed a different way of thinking, and although he knew that his thinking was not going to be liked by a lot of people, he went on. He also helped invent modern anthropology, as well as an approach toward education that remains challenging and inspiring to this day.11 Jean-Jacques Rousseau passed away on July 2, 1778 in Ermenonville, France, but will always live in history.

- Jean-Jacque Rousseau, Social Contract & Discourses (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1913), 2. ↵

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, November 2012, s.v. “Jean-Jacques Rousseau,” by Christopher Bertram. ↵

- Maurice Cranston, Jean-Jacques: The Early Life and Work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), 23. ↵

- Maurice Cranston, The Noble Savage: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1754–1762 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.), 22. ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, June 2015, s.v. “Jean-Jacques Rousseau”, by Maurice Cranston. ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, June 2015, s.v. “Jean-Jacques Rousseau,” by Maurice Cranston. ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, June 2015, s.v. “Jean-Jacques Rousseau,” by Maurice Cranston. ↵

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (New York: Random House, 1945), 45, 48, 57. ↵

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality Polemics, and Political Economy, transl. Rodger D. Masters and Christopher Kelly (New York: St. Martin’s Press , 1964), 21, 27, 40, 42. ↵

- David Lay Williams, Rousseau’s Social Contract: An Introduction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 14, 17. ↵

- Leopold Damrosch, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005), 33. ↵

42 comments

Ruben Basaldu

Probably like many I had no idea who this Jean-Jacques Rousseau guy was before reading this article. However, this article was very well written and also very interesting to read. His thinking was not like others in his time and I actually think that was a good thing. He believed that all men are equal during a time when that was not thought by most. Rousseau has helped shape the way that philosophy is looked at today just by how he saw things back in the day.

Danielle Slaughter

Rousseau is one of my favorite Englightenment philosophers. While I do not agree with every one of his stances – I personally believe that scientific progress and an increase in knowledge is immensely beneficial to humanity – I admire him for daring to be a maverick at a time when going against the grain was usually frowned upon. That, and the fact that he was self-taught, are a testament to his character and resolve.

Diego Terrazas

The fact that Rousseau was self-taught is amazing to me. I feel as if because he is self-taught his philosophy is void of bias due to a lack of influence from an academy or teachers that thought a certain way. Perhaps he was influenced by the Greek city-states and Ancient Greece in general hence his heavily democratic reasoning. His social contract was definitely revolutionary.

Victoria Rodriguez

Rousseau’s ideas were well ahead of his time. I have heard of his philosophies plenty of times in philosophy and in everyday conversation with politics. His ideas were applicable to everyday life and proved that the society in which one lives in sets standards. It is ironic that his philosophy was on society and that in turn society judged his work. Overall great article. A job well done!

Roman Olivera

Jean-Jacques Rousseau is someone that I had never heard of prior to this article. He seemed to be one of the greatest minds of his generation. The issue that he brought up in a time where he was greatly criticized for his views and not given recognition due to his social status or him being only the son of a watch maker. His recognition and social status could have been greatly altered by the attention he was given by the king. He did not want that, he wanted people to be treated like people with equal ability to prove themselves as capable of becoming as great as the next person given the opportunity.

Stephanie Silvola

Rousseau may have acted like the kid that was unpopular but he in fact was ahead of everyone of his time. He described society’s way of thinking between the statuses of the people. Jean would’ve been liked by the people of this generation. He describes how a man is free until he is chained by society in particular situations which I think is true. This article described Jean in a way I can understand since I have never really learned about Jean in the Enlightenment era where in this era ideas and individualism were emphasized more rather than tradition.

Caden Floyd

I had no idea who Jean-Jacques Rousseau was before reading this article, but now I know how much of an impact he had on societies way of thinking. During the time I’m sure his way of thinking was very odd and unpopular. He claimed that all people were born equal until you make yourself be controlled or contained. His way of thinking was way ahead of his time. The enlightenment era now seems like one of the most important eras to me. Rousseau’s mind was simply to complex to just be a watch maker.

Marina Castro

Great article! Rosseau was a man who was revolutionary in his time. Not many people were claiming that every man was equal or born good. During his time people, and society as a whole, had a lot of double-standards. Also, people were divided into classes. For him to claim such a thing had a great impact on the minds of others.

Anna Guaderrama

This was such an interesting article. I never had heard of Jean-Jacques Rousseau before. I loved reading this article because it clearly described who he was and what he did. I can only imagine the pressure of being ‘woke’ and having nobody agree with you. But, then again I can see how shocking it must have been to read it first hand and basically be told things you had never generally thought or would dare to think. I find it fascinating however how even in the midst of such opinion, he challenged the time period and became this controversial writer.

Samuel Ruiz

It never ceases to amaze me when unexpected people write fascinating works. It must have been tough for Rousseau to overcome the pressure to be a watchmaker especially with his passionate and ongoing mind. It was interesting to find that he created a series of writings to tell that the philosophies and advancement of thinking of the time would doom humanity.