After midnight, on the morning of September 19, 1910, Clarence Halsted was awakened by a man entering his ground-floor bedroom window on Church Street in the Englewood section of Chicago. The intruder was seated on the windowsill and lit a match. Mr. Halsted rose from his bed and tried to grab the intruder, but the intruder went back out the window and fled, but Mr. Halsted caught hold of the man’s coat pocket, tearing it. At 2.00 a.m. the same night, someone entered the McNabb house, which was around the corner from Mr. Halsted’s house. The man, described as “tall, broad shouldered, and very dark,” approached Mrs. McNabb’s bed and put his hand under her clothes against her bare body.1 The intruder fled down the stairs after Mrs. McNabb pushed his hand away and cried out. A few minutes later, the Hiller Family also discovered an intruder in their house when he was seen in fifteen-year-old Clarice Hiller’s room. Clarice Hiller was awakened by a man holding a lighted match in her bedroom doorway. Then he entered the thirteen-year-old Florence’s bedroom and pushed up her nightgown and touched her bare body. He left the room and came face to face with the girls’ father, Clarence Hiller. The two men grappled and rolled down the stairs. When they reached the bottom, the intruder pulled out a gun and shot Mr. Hiller once in the neck and once in the chest, killing him almost instantly.2

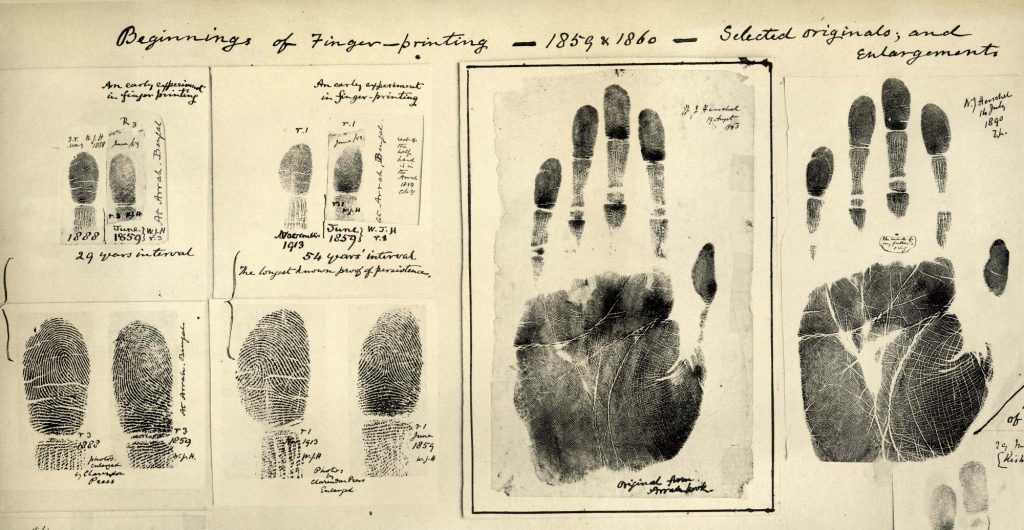

Cases like these have been crucial to the need of forensic science to aid in crime scene investigation. Forensic science has been in the process of development, advancing in technology and techniques over the years. However, the most innovative technique that became the turning point in Forensic Science was the development of fingerprint identification. A murder case in South London, known as The Farrow Case, which happened in 1905, was the first case ever to use fingerprint analysis to aid in identifying a criminal in court.3 In consequence, there was a case in the United States that was able to use fingerprint evidence in court for the first time. This case was the Clarence Hiller Case, People v. Jennings. These two cases are related because the United States needed help to identify the fingerprint evidence in the murder of Clarence Hiller, and Scotland Yard was their best bet in recovering the evidence left at the scene of the crime.

Before fingerprint evidence became the new way of identifying a criminal, there was a system called the Bertillon System, created by a man named Alphonse Bertillon. Alphonse Bertillon, born in 1853, was a rebellious man who tried a variety of careers before his family’s influence secured a position for him with the Prefecture of the Paris Police on March 15, 1879. It was at this time that Bertillon began taking measurements of certain bony portions of the body, among them the skull width, foot length, cubit, trunk and left middle finger. These measurements, along with hair color, eye color, and front and side view photographs, were recorded on cardboard forms measuring six and a half inches tall by five and a half inches wide. This process became known as the Bertillon System. Standardization of the Bertillon System throughout the civilized world meant that, for the first time in recorded history, any individual, once properly classified, could be positively identified later.4

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The benefit to police agencies was incalculable. However, claims that this system would deplete the ranks of the professional criminals were somewhat overly-optimistic and premature. Bertillon devised a method to document and study the victim’s body and circumstances of death. Using a camera on a high tripod, lens facing the ground, a police photographer made top-down views of the crime scene to record all the details in the immediate vicinity of a victim’s body. Early in the twentieth century, police departments began to use Bertillon’s method to photograph murder scenes.5 Bertillon died on Feb. 13, 1914, in Paris. His anthropometric method of identifying recidivists represented a first step toward scientific criminology. It is said that his work played an important role in inspiring greater confidence in police authorities and in establishing a more favorable sense of justice toward the end of the nineteenth century.6 In 1903, the Bertillon System took a bad turn when it was used on the Will West Case. A reporter named Don Whitehead said, “It was this incident that caused the Bertillon System to fall flat on its face.”7

On May 1, 1903, an African American man named Will West entered the United States Penitentiary at Leavenworth. West was subjected to the standard admission procedure: prison clerks took photographs, a physical description, and eleven anthropometric measurements. When taking West’s measurements and description, identification clerks matched him to the record of another William West, who had a previous conviction for murder. Not surprisingly, through the clerks’ view, West denied that he was this man. The discovery of Will West’s past conviction must have seemed routine in the Leavenworth clerks’ view: once again, the world-famous Bertillon System of identification had prevented a criminal from escaping his past. The incident suddenly deviated from the usual, however, when the clerks discovered to their amazement that this same William West was already incarcerated at Leavenworth. The second West was summoned, and he looked startlingly like the first. Their faith in anthropometry shaken, the clerks fingerprinted the two men, and their fingerprints were completely different. 8

As the Bertillon System began to decline, the use of fingerprints in identifying and classifying individuals began to rise. After 1903, many prison systems began to use fingerprints as the primary way to identify a suspect.9 Bertillon measurements are difficult to take with uniform exactness, and physical dimensions can change as a result of growth or surgery. For these reasons, fingerprinting and other methods have, for the most part, superseded the Bertillon system as the principal means of identification in American and European police systems.10

Thomas Jennings, an ex-convict, a Negro “laboring man,” was apprehended three-quarters of a mile from the Hillers’ house thirteen minutes after the shooting by four off-duty police officers who, unaware of the murder, saw blood on his shirt and found a .38 caliber revolver in his pocket.11 The revolver contained cartridges which matched those found at the crime scene of Mr. Hiller, and residue of gunshots of recent firing, Jennings’ coat pocket was torn in a manner consistent with that described by Halsted, and he had fresh cuts that may have been defensive wounds. Jennings contended that he had torn his coat at work, had injured his hand by falling off a streetcar, and had never fired his revolver. Neither of the witnesses saw the intruder’s face in the dark; they were only able to describe his build and said he was a colored man. Clarence Halsted, Mrs. McNabb, and her daughter Jessie testified that Jennings looked like the man that broke into their houses that night. The three break-ins plus the murder case were found to be connected since they all were in the same area and the times matched from Jennings starting with Halsted’s house after about 1:30 a.m., then going to Mrs. McNabb’s house at about 2 a.m. and shortly after 2 a.m. Jennings was at the Hiller’s home. Additionally, the first two break-ins had similar descriptions and Clarence Hiller murderer was already identified after the police saw Jennings plus the blood and gun that had residue. In a matter reminiscent of the West case, the Chicago Police Department called in its fingerprint examiners to individualize a “colored” man, whom witnesses could not identify except to say that he was colored.12 William Evans worked for his father Michael Evans at the Chicago Police Department’s Bureau of Identification and he found finger impressions in the recently dried paint on Hiller’s porch railing, and he matched the prints to inked prints taken from Jennings.

Fingerprinting was new enough to warrant an extended debate over its validity as a forensic technique in the trial. Five fingerprint examiners testified as expert witnesses: Michael and William Evans; another Evans son, Edward, formerly of the Bureau of identification, who had taken prints from Jennings upon earlier arrest; Edward Foster, chief of the Bureau of Identification of the Canada Dominion Police; and Mary Holland, head of the U.S. Navy Bureau of Identification. All five had been trained in the fingerprint identification by Detective John Ferrier of Scotland Yard at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Foster and Holland testified that they had subsequently traveled to London for further instruction and they had passed proficiency tests at the Yard.13 All five of them agreed that the print found in the paint of the porch railing matched Jennings’ print. Foster testified that he had never seen two fingerprints with ridge characteristics so “exactly alike.”14 He portrayed the identity of the two prints as a matter of fact rather than interpretation.

At Jennings’ May 1911 trial, there were two Chicago Police Department fingerprint examiners, a fingerprint technician from the police department in Ottawa, Canada, and a private expert who had studied fingerprint science at Scotland Yard in Victoria, London, who testified that the impressions on the porch rail matched the ridges on four of the defendant’s fingers, placing him at the scene of the murder. While fingerprints had been around for about twenty years, this was the first U.S. jury to be presented with this form of impression evidence. The chance of convicting Jennings was difficult due to the defendant’s arrest one mile from the house, his injuries, his possession of a recently fired gun, and his murder scene fingerprints, all being circumstantial evidence. In those days, and to some extent today, jurors prefer direct evidence in the form of confessions and eyewitness identifications.15

Thomas Jennings went to trial charged with the murder of Clarence Hiller. Thomas’ lawyer insisted that the fingerprint evidence was not recognized by the laws of Illinois and shouldn’t be admissible in court. However, the judge disagreed and allowed the evidence, Jennings was subsequently convicted of the murder of Clarence Hiller, and sentenced to death. This was good news for forensic science, and bad news for Thomas Jennings, who died in 1912 at the end of a rope.16

In order to understand the modern-day importance of fingerprint evidence in the United States legal system, one must be familiar with important early legal cases. One such case is People v. Jennings (1911).17 People v. Jennings laid the groundwork for forensic fingerprint identification in America. By 1925, virtually every court in the United States accepted this form of impression evidence as proof of guilt. In medicine, illness leads to cures, and in law enforcement, murders produce advances in forensic science.18

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 177. ↵

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 178. ↵

- “Fingerprint Evidence Is Used to Solve a British Murder Case,” History.com (blog). November 13, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fingerprint-evidence-is-used-to-solve-a-british-murder-case. ↵

- “Identification Systems in New York State: The Bertillon System,” NYS Division of Criminal Services, (1997). ↵

- “Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body: Galleries: Technologies: The Bertillon System.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 05, 2014. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/visibleproofs/galleries/technologies/bertillon.html. ↵

- In Encyclopedia of World Biography 2004, s.v. “Alphonse Bertillon.” ↵

- David Love, “For Black People, Fingerprinting Is a Double-Edged Sword, Sweeping Up the Innocent,” Atlanta Black Star (website), April 10, 2016. https://atlantablackstar.com/2016/04/10/for-black-people-fingerprinting-is-a-double-edged-sword-sweeping-up-the-innocent/ ↵

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 140-145. ↵

- “History of Fingerprints,” Crime Scene Forensics, LLC, 2015. http://www.crimescene-forensics.com/Crime_Scene_Forensics/History_of_Fingerprints.html ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, January 1, 2018, s.v. “Bertillon System.” ↵

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 178. ↵

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 178. ↵

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 178-179. ↵

- Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identifies: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 179. ↵

- Jim Fisher, “The Historic Fingerprint: The Jennings Murder Case,” Jim Fisher True Crime (blog), January 01, 1970. http://jimfishertruecrime.blogspot.com/2012/03/historic-fingerprint-jennings-case.html. ↵

- Jim Fisher, “The Historic Fingerprint: The Jennings Murder Case,” Jim Fisher True Crime (blog), January 01, 1970. http://jimfishertruecrime.blogspot.com/2012/03/historic-fingerprint-jennings-case.html. ↵

- Mark A. Acree, “People v. Jennings: A significant case for fingerprint science in America,” Journal of Forensic Identification, (Jul/Aug 1999): 455. ↵

- Jim Fisher, “The Historic Fingerprint: The Jennings Murder Case,” Jim Fisher True Crime (blog), January 01, 1970. http://jimfishertruecrime.blogspot.com/2012/03/historic-fingerprint-jennings-case.html. ↵

78 comments

Katherine

Wow, this article is pretty good! Really helped me learn about a topic I didn’t previously know about! But I think you got Clarence Hiller’s name wrong—you wrote “Clarence Halsted.”

Kristina Heerdegen

Hi Diamond! I literally could not stop reading this article, especially with the opener I just had to know where you were going to go with it! I literally had goosebumps in the first paragraph! It is so interesting to see the way that technology has advanced so much and has allowed us to get so much more information out of crime scenes like you discussed! Thank you for this!

Lyzette Flores

Hi Diamond! Good job on your article. I like the way it was structured from introducing a few cases, to introducing the finger print system, following up with the old structure: Bertillon system. I never knew how police would identify criminals before the finger system came into play. You’re right; it is important to be familiar with the early cases in order to understand how the finger print system was developed. Your article was very interesting to read.

Diego Oviedo

This article was very intriguing. I enjoyed how it kept the reader wanting to read more and used the cases in detail about what happened. I don’t really know much about forensics but it was very interesting how they utilize what they have to solve cases, especially ones like these. It’s amazing how fingerprints have made it easier to catch people and to solve cases.

Margaret Cavazos

This article was an interesting read! I liked how it gave the history of identification while including a criminal court case for emphasis and to keep the reader captivated. It seems almost unbelievable that courts went from full body measurements as a means of identification to something as small and simple as fingerprints and handprints. I understand why the court may have a hard time adjusting to the new system of identification but I imagine this made it easier for them to identify people.

Davis Nickle

It’s a good thing that we began to utilize peoples fingerprints to trace criminals. From what was spoken of the Bertillon Stem makes me think that it was very complicated and required many measurements to be taken, and even then it was not all to reliable. I imagine without the use of fingerprints many cases today would be left unsolved. And it was mold breaking cases like these that showed the importance of fingerprints in forensic science.

Aracely Beltran

Well written article! All I have to say is, I am grateful for fingerprints. Those do not lie, they are all so similar yet so different. Also thank God the police keep a record of everything or else they probably would not have anything on this man. That poor woman and girl that went through that! I would probably die.

Melanie Fraire

I had no knowledge on this case prior to reading this article however I found the case to be very interesting. Forensics has always interested me as well and learning about the many advancements it has made over the years is really cool since it’s come so far to the point that our current method of using fingerprints is pretty reliable when it comes to convicting someone.

Brandon Torres

Prior to reading this article, I never knew about this case, or even this monumental system (the Bertillon), however thanks to this article, I now understand how its effective nature eventually paved the way for modern forensic fingerprinting! Along with being blown away by the details of the system, I was also very impressed with the explanation that went behind its usage and eventual aid as a trailblazer! The author really did their research in this writing and thankfully, it is shown off from both the emphasis from this case to the future ones that came at its inevitable evolution!

Amanda Shoemaker

I never knew that finger printing was around in the early 1900’s. Fingerprinting is used for so much now that it’s weird to think about a time that it wasn’t used, This article does a great job of showing how important the discovery of fingerprinting was. It was vital to the advancement of law enforcement and modern criminology. Overall, this article was very interesting and really gave insight to the importance of fingerprinting.