As one walks into school on their first day, feeling nervous is normal to most. But in 1960, walking into a newly integrated school as a black student meant extreme danger and numerous threats. There would be crowds of dozens, maybe hundreds of people yelling obscenities in your face from all directions. There would be death threats, and people even trying to spit on you. Such a horrific state of entering school was a reality to many young black students, especially to Ruby Bridges, who, on November 14, 1960, was the first black student to attend the all-white William Frantz Public School in New Orleans, Louisiana. This is what the United States of America looked like in the early 1960’s. It was full of hate and intolerance. But before Ruby had the opportunity of attending an integrated school, it was the work of the NAACP and numerous lawyers that brought about the end of school segregation in the country permanently. In 1954, a leap towards granting a form of equality was enacted. The Supreme Court ruling in The Brown v Board of Education decision was a catalyst for bringing about a new country for people of color.

“We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does… We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”1

T he Brown v. Board of Education decision allowing integration in schools began a surge and kept the fire blazing in the long-lasting fight for equal rights for the entire black community. The Brown v. Board decision revoked the previous case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which, in 1896, introduced the separate but equal principle. The separate but equal idea was not just, as it emphasized segregation and did in fact not guarantee anything equal. Signs throughout the South emphasized the segregation by establishing “white only” or “no colored” criteria. This separation between white people and black people was found everywhere, including restaurants, movie theaters, water fountains, rest rooms, and schools.2Through the legal fighting of attorney Thurgood Marshall and many others, the Supreme Court was faced with the legal decision of formally integrating public schools nationally. On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Warren and the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously voted that the separate but equal doctrine was in full violation with the Fourteenth Amendment in accordance to education, and that black students were entitled to the full and equal protection of the law that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed. But what this court decision did not have was exact instructions for how schools were to begin the process of integrating their schools. In the following year of 1955, Brown II was reviewed by the Supreme Court because of the lack of progress schools had shown in integrating their schools. Because of this, Chief Justice Warren stated that following Brown II, it was mandatory that all comply with the ruling of “Brown v. Board of Education” in a quick and speedy manner. It was decided that lower courts were responsible for making the school authorities take the action needed in order to desegregate. But, there was also recognition that it would take time to fully integrate schools because of the known backlash that the white community would broadcast.3

Of course, the school board and white citizens did not want to allow the mixing of children to take place so easily. In Virginia, Prince Edward County closed their public schools through the years 1959 and 1964 for the sole purpose of preventing school integration. Even by 1965, the highly segregated South had only two percent of black children integrated into their school systems, and seventy-five percent of the schools remained segregated.4

But in New Orleans, there was one little girl who did not back down in the face of hate. Ruby Nell Bridges was born September 8, 1954, in Tylertown, Mississippi, the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court had made the Brown v. Board of Education decision. This is a remarkable coincidence, as Ruby Bridges proves to be one of the strongest advocates and faces for the integration of schools in the United States of America.5

At the age of four, Ruby’s parents, Abon and Lucielle Bridges, moved their family to New Orleans, Louisiana in hopes of making a better life for themselves. By the time Ruby was in Kindergarten she was chosen to take a test that would determine who would be allowed to attend an all-white school. The test was made to be difficult in order to set up the black students to fail, and if all black students failed, then this gave the school district the only justification they thought they needed to keep their schools segregated. Avon Bridges, Ruby’s father, was apprehensive at allowing Ruby to even take the test. He knew that if she passed, she would have a spot in a white school, and this could introduce her to a wide array of dangers. Ruby’s mother, Lucille Bridges, on the other hand saw the opportunity Ruby was being offered. Lucille was aware that the white school would offer a better education for her child, and she eventually convinced her husband to allow Ruby to take the test.6

Ruby, despite the difficult test put before her, showed how bright she truly was, and was one of only six other black students who had passed. This meant that Ruby Bridges would now attend William Frantz Public School, which was only five blocks from her house. Previously, Ruby attended kindergarten at a segregated all-black school several miles away. The summer before school began, the Louisiana State Legislature had been fighting the federal court order in hopes to put a halt or slow down the integration process. But after months of trying to fight a court order, the designated schools were allowed to integrate in November.7

It was November 14, 1960, and Ruby Bridges was the first black student to attend an all-white school in the South. The danger Ruby was about to encounter was obvious, and it was expected that civil disturbances would take place. For Ruby’s safety, a judge from the federal district court had the U.S. government send federal marshals down to New Orleans to be at Ruby’s side.

Ruby and her mother were driven by federal marshals five blocks down the road to her new school. During the ride, one federal marshal explained that Ruby was to walk behind two marshals and two more would be behind her. Upon arrival there was a large group of people, policemen, and barricades all around. Ruby faced the yelling of horrible words by dozens of people who did not want her attending the school, and even objects were thrown her way. She eventually made it through the doors of the school where she went to the principal’s office, where she spent the entire day. This was because nearly all of the white parents had taken their children out of school in protest, so no classes were being held because of the lack of students.8

Ruby was not afraid and defied the ignorance that gathered around the school, and she returned the next day. The circumstances were proving to be the same, and no one was stepping up to take Ruby into their classroom. Finally, a new teacher, Barbara Henry, from Boston, openly agreed to teach Ruby. Mrs. Henry was not like the other closed minded and hateful teachers that taught at William Frantz Public School. She took Ruby in with nothing less than open arms. But because of the frantic white parents threatening to permanently pull their children from the school if placed in the same classroom as Ruby, she was the only student in her classroom. For the duration of the school year, Ruby and Mrs. Henry sat, side by side, working at two desks on Ruby’s lessons.9

What Ruby faced for weeks when entering school by white adults and their children is nothing less than disgusting. After Ruby’s second day, federal marshals only allowed her to eat food from home after one woman had threatened to poison her. Later, another woman had brought a black doll in a wooden coffin to the school and waved it in Ruby’s view. With Ruby’s encouragement from home, she never let her head down, but held it high in pride. Ruby’s mother kept reminding Ruby to be strong, and even encouraged her to pray while she entered school, and Ruby did. With words of prayer, Ruby felt courage and a shield was brought before her that ricocheted all of the vile things being yelled her way. Charles Burks, one of the federal marshal escorts, pridefully commented that Ruby was the epitome of courage. “She never cried or whimpered. She just marched along like a little soldier.”10 Ruby was not allowed to leave her classroom during the day, even for lunch, or to go play at recess. Even during her bathroom breaks, she had to be escorted by the federal marshals down the hallway to the restroom.11

Sadly, the negativity that Ruby was facing was also being directed at her entire family. Ruby’s father lost his job due to the controversy, and her grandparents were sent off of the land they had sharecropped for nearly three decades. The neighborhood grocery store that the family had used banned them from even entering. But, people in their community began to show them love and support, despite the negativity they were facing. A neighbor offered Ruby’s father a new job, many volunteered to babysit Ruby and her siblings if need be, others watched their house in order to protect it, and others walked behind the federal marshals when taking Ruby to school. With Ruby being so young, and the great amount of negative attention she was receiving, she started to show signs of stress. She would wake her mother during the middle of the night because of nightmares, and Ruby desired her mother’s comfort. Ruby ate lunch alone in her classroom, but she eventually stopped eating the food her mother would pack for her. She turned to hiding the uneaten food in cabinets of the classroom. When mice and cockroaches began to emerge, the janitor made the discovery of the food hidden by Ruby. This pushed Mrs. Henry to begin eating lunch everyday with Ruby in the same classroom.12 In regards to Ruby, Mrs. Henry stated, “Ruby was an extraordinary little girl. She was a child who exuded, I think, courage. To think that every day she would come to class knowing that she would not have any children to play with, to be with, to talk to, and yet continually she came to school happily, and interested to learn whatever could be offered to her.”[ 12. Carol Brennan, Contemporary Black Biography (Michigan: Gale, 2010), 28-30.]

A child psychologist, Dr. Robert Coles, volunteered to start seeing Ruby while she was at William Frantz Public School. He, among others, was concerned for her well being and how she was coping with being at this new school and the terrible pressure she was under at such a young age. He visited Ruby once a week to check on how she was doing. They would talk about her experiences, how she was feeling, and would even color pictures together. Towards the end of the school year, the angry crowds began to settle down. Small amounts of children in Ruby’s grade had returned, and on rare occasions, Ruby got to interact with them. Ruby was not aware of the extent of the roaring racism around her until children rejected her friendship strictly due to her race. When it was Ruby’s second year of school at William Frantz, there had been some changes. Ruby walked herself to school everyday without federal marshals. Mrs. Henry’s contract had not been renewed and she had returned to Boston. Ruby also had other students in her class and the school began to actually fill up to full enrollment again.13

“Our Ruby taught us a lot. She became someone who helped change our country. She was part of history, just like generals and presidents are part of history. They’re leaders and so was Ruby. She led us away from hate, and she led us nearer to knowing each other, the white folks and the black folks.”14 —Ruby’s Mother

After finishing grade school, Ruby Bridges graduated from Francis T. Nicholls High School in New Orleans. She later went to Kansas City business school and studied travel and tourism. She worked as a world travel agent for American Express and was married in 1984 to Malcolm Hall. She had four sons and became a full time parent. Malcolm Bridges, Ruby’s youngest bother, was murdered in 1993 and Ruby took in Malcolm’s four children who were then going to attend William Frantz Public School, the same school Ruby had attended when she was young. She became an active volunteer in the very school where she had made history decades earlier. In 1999, Ruby formed the Ruby Bridges Foundation that is headquartered in New Orleans. The foundation promotes the appreciation of all differences, and highlights the importance of respect and overall tolerance. They hope to spread the importance of education, inspire children, and see the end of all prejudice and racism. The foundation states, “Racism is a grown up disease and we must stop using our children to spread it.”15

Ruby Nell Bridges was only six years old when she walked bravely into a new school and faced a cruel world she had barely known. What she did at such a young age with pure valor and dedication makes her a hero to this nation and the catalyst of a country that needed to see change. What Ruby did was pave the way for that change, and her story will continue to inspire all of us for generations to come.

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Brown v. Board of Education,” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Brown v. Board of Education,” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Brown v. Board of Education,” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Brown v. Board of Education,” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- “Ruby Bridges Biography.com,” A&E Television Networks (April 27, 2017). ↵

- Carol Brennan, Contemporary Black Biography (Michigan: Gale, 2010), 28-30. ↵

- Carol Brennan, Contemporary Black Biography (Michigan: Gale, 2010), 28-30. ↵

- “Ruby Bridges Biography .com,” A&E Television Networks (April 27, 2017). ↵

- “Ruby Bridges Biography .com,” A&E Television Networks (April 27, 2017). ↵

- Carol Brennan, Contemporary Black Biography (Michigan: Gale, 2010), 28-30. ↵

- Carol Brennan, Contemporary Black Biography (Michigan: Gale, 2010), 28-30. ↵

- “Ruby Bridges Biography.com,” A&E Television Networks (April 27, 2017). ↵

- Carol Brennan, Contemporary Black Biography (Michigan: Gale, 2010), 28-30. ↵

- Robert Coles, The Story of Ruby Bridges (New York: Scholastic, 1995), 1. ↵

- “Ruby Bridges Biography .com,” A&E Television Networks (April 27, 2017). ↵

82 comments

Cherice Leach

Segregation is something that I, luckily, have never had the chance to experience. Reading about Ruby’s situation, and how scary it must be was harrowing for me. I’ve changed schools several times as a child living with a father in the military, but I can only imagine that the nervousness I always faced each time as the “new kid”, was only a fraction of what Ruby persevered through in her life.

Samman Tyata

I really liked the way you have structured you article. This is my second time reading this article and I really loved reading it once again. It is always tough to look back at the times of segregation in America. I am really glad that this doesn’t exist now. It is inspiring that being so small she faced and coped will all the changes. In closing, it was a good read once again.

Megan Barnett

The struggles Ruby Bridges had to go through were terrible, but her way of approaching them was exceptional. Who would have thought that at such a young age a little girl could make history and change the views people had towards others with a different race? The strength Ruby showed as well as her family is outstanding and it is sad to hear that others were so cruel to them.

Karina Nanez

What an incredible story to read. How awful that Ruby had to face such open discrimination and hatred just because she was African American, even more incredible is that she was able to face it all head on at the young age of six. You did a truly wonderful job narrating this story and describing how she overcame this hatred.

Erik Shannon

This is a very interesting article. Before reading this article, I knew allot about Ruby Bridges and her many, many accomplishments. She has an amazing story behind her life. This article did an amazing job and showing us the story of her life more than telling us. It is crazy she went through so much at such a young age. Thanks to her, allot has changed in our history. Overall, very good article.

Brianda Gomez

It truly is heartbreaking to know how people can be so heartless and say horrible things to people, especially such a young girl like Ruby Bridges. Before reading this article, I did not know that some students had to take an exam to attend an all-white school and that these tests were also set up to make the students fail. It is truly amazing to learn about Ruby and learn how she broke the rules and lead the way for many other students just like herself. This was such a well-written article!

Christine Sackey

This article was very informative. Ruby Nell Bridges was a brave little girl and I can not imagine the amount of pressure she must have felt. It was a major opportunity for her and her family and it made history. She broke the walls down for African Americans to get the proper education that they deserve. Her teacher seemed like a nice lady and it shows that are great teachers who are really concerned about their students. Racism is a nasty thing that should occur because we are all humans with the same needs and wants. Courageous people like Ruby show that change can occur if you work for it.

Tyler Sleeter

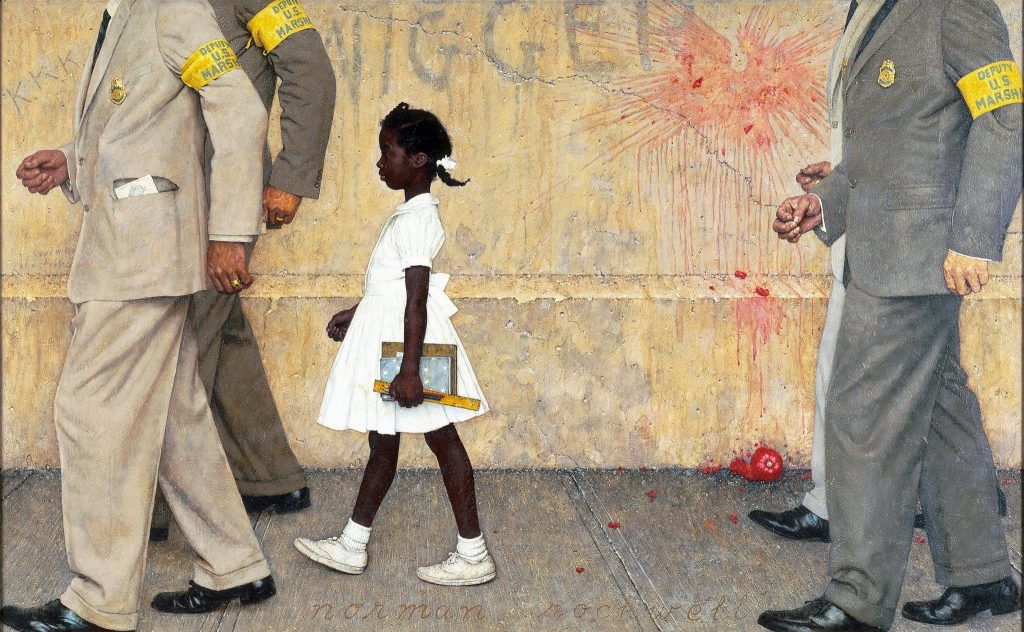

Really great story, loved it! Like most students I am familiar with the desegregation of the public school by the Supreme Court. I am also aware that most southern whites did not embrace this decision. However, I have never heard of Ruby Bridges although I have seen the Norman Rockwall painting. I was so glad to hear that Ruby got some counseling help for all the stress this had to have had upon her. I cannot imagine how much hate it would take to throw things at a small little girl who was only trying to walk to school. I was surprised to hear that her grandchildren now go to the same school she attended so long ago.

Maria Callejas

GREAT FEATURE IMAGE, the cool thing is that it is a painting of the event, so it adds more significance to it. I knew little about Ruby Bridges, I had seen the famous picture of her with the two officers at the school steps. But you did a great job providing information about what went down in Ruby’s school. At such a young age, Ruby became an inspiration for many. It is amazing to see how much America has progressed since the highly segregated 60’s. Great article!

Mario Sosa

Very powerful imagery all throughout the article, especially the featured image. It is incredibly hard to imagine today that around 50 years ago, many people strongly wanted to preserve segregation. I do admire Ruby Bridges for being brave and courageous during those hard times, and also her parents who gave her the strength to do so. Nicely structured and well made article; great job!