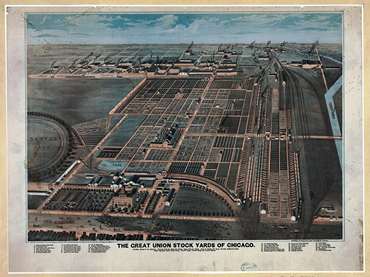

Upton Sinclair wanted more people to read his work. He needed something interesting enough to get the general population upset. After Sinclair’s semi-success with his novel Manassas, he wanted more praise. But it had only sold less than two-thousand copies. Sinclair had portrayed slavery, its struggles, and its effects in Manassas. Sinclair later said of this, “Nevertheless, Manassas was the means of leading me out of the woods.”1 His first socialist commentary on society would be the platform for Sinclair to write the largest exposé of the era. After its mild success in socialist circles, Sinclair was approached by the editor of a socialist magazine, Appeal to Reason, in 1904. He was asked by Fred Warren to write about the wage slavery problem in immigrant communities. Chicago had one of the largest Beef Trusts in the country, and Upton set his sights on it.

Upton Sinclair was born on September 20, 1878, in Baltimore, Maryland. His family had fallen on hard times after the Civil War. His father, Upton Sinclair Sr., was an alcoholic salesman, while his mother, Priscilla Sinclair, was a house maker who tutored young Upton until the age of ten. After moving to New York in 1888, he began school despite concern for his physical health. In 1892, at the age of fourteen, he entered city college to study literature and philosophy, and then he went to Columbia University. To help his family make ends meet, he wrote under pseudonyms in newspapers and “dime novels” for young boys to read. In 1900, he married a family friend, Meta Fuller, and had a son soon after. He only wished to write, so they lived in extreme poverty, hopping between houses of friends and family. In 1903, he moved his wife and young son to Princeton, New Jersey, to be closer to Civil War archives. He needed these to work on his upcoming book, Manassas, a novel about a Civil War soldier.

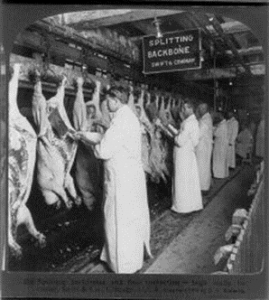

In 1904, Sinclair set his sights on another writing project. “In October 1904, I set out for Chicago, and for seven weeks lived among the wage slaves of the Beef Trust. I sat at night in the homes of the workers, foreign-born and native, and they told me their stories, one after one, and I made notes of everything.”2 Sinclair stayed with different immigrant families for seven weeks, listening to horror after horror. Many of these immigrant families could not afford to stop working, because their wages were so low. The only money they brought in was spent on food, rent, and any other expenses, meaning that they were wage slaves. The stories they told Sinclair shook him to the bone, rattling him, but he continued on though the weeks, writing down everything he heard. Stories of rats falling in the meat processing machines, and mixing spoiled meat with healthy meat so as not waste any product, were told by these workers. Sinclair was hesitant about all of the stories he had collected, so he went to Adolphe Smith, a founder of the Social-Democratic Federation in England. Smith told Sinclair, “These are not packing plants at all, these are packing boxes crammed with wage slaves.”3

After this interaction, Sinclair knew he had to continue writing these horrific stories, to end this cycle of wage slavery and abuse. He knew that it was his job to bring this wage slavery to the public’s eye. Upton not only talked to the workers in the stockyards, but also to anyone in the neighborhoods he canvased. He talked to healthcare workers and how the horrible injuries from the stockyard never healed right, and often put workers out of their job. He made friends with other progressives and writers of the era, with Jack London, and Jane Addams of Hull House, and Mary MacDowell, who told him more stories of the horrific lives of the workers in Chicago. Sinclair stopped everyone on the streets and asked for their stories. He remembers, “When the book appeared, they were a little shocked to find how bad it seemed to the outside world.”3

Upton Sinclair had the base for a tell-all story, but how should he deliver it? There was no way he could think of how to deliver such gruesome stories in just an informative book or essay. As he pondered this one evening while walking, Sinclair came across a wedding party. Watching them from afar, he followed them. He heard the loud music from the dance hall and slipped in, watching the family party from a back corner. As he watched them, he created the characters of The Jungle. While writing, Sinclair thought of his own family’s experiences, and how starkly different they were from the families in the Chicago stockyards, even while still being poor throughout most of his adult life. The winter that Sinclair was writing, his son became so sick with Pneumonia, that he almost died. Sinclair used his grief of almost loosing his son, he wrote of the experience, “Our little boy was down with pneumonia that winter, and nearly died, and the grief of that went into the book.”5 He wrote the novel over a three month period, in his family cabin.

Appeal to Reason published the first chapters of The Jungle, and it was praised by the readers. They wrote Sinclair, telling him how shocked and horrified they were. One reader, David Graham Phillips, wrote to Sinclair, “I am afraid to trust myself to tell you how it affects me.”6 The editor for the publishing company Macmillian had read the first chapters and wanted to publish the novel in its entirety. Sinclair was given an advance of $500 to finish the novel. By that time, however, most of his money had run out, and he could not make a second trip to Chicago. And on top of that, he had started to have serious health problems. Sinclair wrote the last chapters of the book trying to wrap up all the loose ends and “solve all the problems of America,” but those chapters received poor reviews from the Macmillian editors.7

George P. Brett, one of those editors, went to visit Sinclair in person while he was finishing the book, to ask him to cut out some of the goriest parts of the book. They were worried that Sinclair had written false stories to embellish his novel. “I have embellished nothing,” Sinclair insisted; “I have invented incidents. I have simply dramatized and interpreted but I have not invented the smallest detail.” Macmillian, not believing Sinclair, declined to publish the novel in full, and so Sinclair kept looking for a publisher. Sinclair asked five different publishers to publish The Jungle and was rejected every time. Finally, a newspaper, Doubleday, sent a lawyer to the Chicago stockyards to investigate the validity of Sinclair’s writing. The stories of rats falling into the meat grinders, selling rotten meat, and locking workers inside the factories were all true. After the lawyer returned and the storied were confirmed, The Jungle was published by Doubleday in February 1906. After it was approved to be published, Sinclair said, “the controversy started at once.”8

The book was condemned by the owners of the stockyards, saying it was an “unscrupulous attacks upon his great business.” 9 Sinclair’s response was an eight-thousand-word essay titled “The Condemned Meat Industry.” He then took a train the very next day to New York to have it published in Everybody’s Magazine. After meeting with the editor-in-chief, he read his article to the entire staff at the magazine. They immediately stopped printing their edition for the next day to put his article in the next edition. Sinclair met with two lawyers and had to go line by line and explain every single statement. But, Sinclair was very unlucky, as the day it was published, San Francisco had one of the worst earthquakes in history. Even though first impressions of the novel had been less popular than Sinclair had hoped, one event made the book explode with popularity. In March of 1906, a press manager from Doubleday and Sinclair both sent copies of the book to President Roosevelt. Sinclair later found out that Roosevelt had been receiving hundreds of letters about the book and they were asking why the government was letting this happen. Roosevelt had written to Sinclair saying he would have the Department of Agriculture investigate the matter in Chicago. Sinclair responded by saying “that was like asking a burglar to determine his own guilt.”9

Only weeks later, Roosevelt delivered a speech denouncing muckrakers and their writing. Roosevelt did, however, call upon the Bureau of Animal Industry to investigate the meatpacking plants, but news of this plan spread quickly. The stockyards had time to clean up and put in temporary regulations when government inspectors came. In 1906, Senator A. J. Beveridge read The Jungle and decided to act. Alongside three other senators, he drafted the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906. “It was passed within weeks by the Senate… as a direct result of disclosures made in Sinclair’s novel.”2 The act prohibited the sale of any food that had been tampered with, any food that included other ingredients not listed, and any spoiled or rotten food. It also included any food that had been changed, colored, or blended to hide impurities. This act helped to start a national standard for food that was priced in the United States.

Upton Sinclair was made extremely wealthy by the popularity of The Jungle. Although the public had rejected his ideas for a socialist solution to the wage slavery problem, they had instead focused on the meat industry. In 1915, Sinclair moved to California where he wrote three more socialist commentary novels: Oil, King Coal, and Boston. All three had dismal public support compared to The Jungle, but he was making waves within the small socialist communities in the country. In the 1930’s, at the peak of the depression, Sinclair ran for Governor of California. He abandoned the socialist party and registered as a Democrat. He lost the race, but his opponent, Frank Mirriam, wrote several pieces of legislation that mirrored Sinclair’s ideas for wage laws and regulations. Sinclair wrote fiction books for the remainder of his life before dying in 1968. His writing affected how meat and other foods were processed in the United States, saving countless lives. Although his initial thoughts were to end wage slavery, The Jungle still made an impact.

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 99. ↵

- Arlene Finger Kantor, “Upton Sinclair and the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906,” American Journal of Public Health 66, no. 12 (December 1976): 1202–5. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 99. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 99. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 115. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 116. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 118. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 120. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 120. ↵

- Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World,1962), 120. ↵

- Arlene Finger Kantor, “Upton Sinclair and the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906,” American Journal of Public Health 66, no. 12 (December 1976): 1202–5. ↵

8 comments

Ben Kruck

This is a good article. I only heard about The Jungle and Upton Sinclair only once, but that was a long time ago, so I got to relearn it all. I liked the overall structure of the article; it went into a lot of detail about what work was like back then, and the use of images was spot on. We have Sinclair and The Jungle to thank for beginning the change of overall work.

Madeline Chandler

This was an extremely well-written article, and it was so detailed. It was so interesting because I do not have much knowledge of the story of Upton Sinclair and his beliefs. This article was very intriguing because it shows how one man tried so hard to make his works known and solve social issues. Even though his works were not as famous, his beliefs on the abuse of immigrants and slave labor have opened the eyes of many people.

Mauricio Rebaza Figueroa

Hi, Lily, this is such a good article. I really didn’t have a previous knowledge about Upton Sinclair before reading your article I could learn more about his story. It is really detailed on these events and I really learned from it. You also used really good images that helped me reading the article and different sources that made it trustworthy. Overall, you did a really good job.

Paula Ferradas Hiraoka

Hello Lily,

First of all, congratulations on your nomination and getting your article published!

This is one of the best articles I’ve read so far. I don’t think I have ever heard of Upton Sinclair, so while reading your article I learned a lot. It’s impressive how a single person can have a huge impact in history, not only writing, but also saving lives of many people in the US. Sinclair seems to have had a really interesting working life.

Overall, amazing article and good luck!

Mary Elizabeth Sommer

Lily,

I had no previous knowledge about Sinckair, but was familiar with the issues on food purity. This was so well written and easy to understand. It was concise and a quick, easy read, which is something that is usually found in other research artocles!

Madeline Emke

An incredible article! Very well-written and the author had a very clear and deep understanding of Upton Sinclair. I had a brief understanding of how the Pure Food and Drug Acts came to be but the article provided a better understanding about the process and reason behind the act. While Sinclair’s goal was very different, the outcome of “The Jungle” can still be felt today.

Vianne Beltran

Hi Lily,

I don’t think I have ever heard of Upton Sinclair. The quote you included in the title caught my attention and drew me into reading your article. I love reading examples of how writing and words can make a noticeable change in society. Sinclair seems to have had a really interesting life. I think wage slavery is still a real problem today but he seems to have helped the conditions of this people a lot.

Andrew Ponce

Great article! It was really interesting to see how such an impactful character of history, impacted history in a much more different way than he had intended. Upton is a character that majority of people recognize, however they recognize him more for his talk in the meat industry rather than his speech on socialism reform. The author provided a different perspective view this person in. It is amusing to see how such an impactful person, became impactful for a reason he truly did not mean to impact so heavily on. Very nice article, and I hope it becomes nominated.