Many issues troubled Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s mind in the waning days of 1940. Most importantly, the state of the war in Europe was exceedingly bleak. The United Kingdom stood alone against the might of Nazi Germany, which had already brought much of Western Europe to its knees. The wealthy and powerful states of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands had fallen under the tyranny of Nazi rule. Should Great Britain suffer a similar fate, and war break out between the United States and Germany, the country would face the daunting prospect of liberating a “Fortress Europe” alone. It was painfully clear to Roosevelt that Great Britain would require assistance if the valiant nation was to carry on the war, much less see it through until the end. Here too, the newly reelected president faced an obstacle: the American ambassador to the United Kingdom, Joseph Kennedy, had been recalled from his post in London, leaving Roosevelt with no ears or eyes in neither the beleaguered city nor the chambers of Whitehall, the seat of British power. Roosevelt mulled over these issues swirling around in his head with his close confidant Harry Hopkins. “You know, a lot of this could be settled if Churchill and I could just sit down together for awhile,” Roosevelt told Hopkins. “What’s stopping you?” Hopkins asked. “Well, it couldn’t be arranged right now. They have no Ambassador here; we have none over there,” the president explained. Sensing an opportunity for “high adventure,” Hopkins suggested that he go to London to represent Roosevelt himself. “How about me going over, Mr. President?” Hopkins suggested. Roosevelt turned the idea down quickly because he was uncomfortable with the idea of letting Hopkins go at such a crucial time in the political life of the nation. The president was counting on his assistance in crucial matters such as drafting a third inaugural address, preparing a State of the Union speech, proposing a budget to put before Congress, and most importantly, shepherding the Lend-Lease Bill through the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. “I’ll be of no use to you in that fight,” Hopkins insisted, “They’d never pay any attention to my views, except to vote the other way. But, if I had been in England and seen it with my own eyes, then I might be of some help.”1 Clearly, Hopkins was intent on making the journey to England, but the president simply would not hear of it. It seemed for the time being that Hopkins was confined to Washington D.C.

Despite Hopkins’ best efforts to convince him otherwise, President Roosevelt remained steadfast that Hopkins should remain in Washington. However, by the dawn of the new year, Roosevelt’s attitude towards Hopkins’ proposed trip had apparently changed. On the morning of January 3, 1941, while working on the soon to be famous “Four Freedoms” speech in his bedroom in the White House, Hopkins received a phone call from Steve Early congratulating him. “On what?” Hopkins asked. “Your trip,” Early replied. “What trip?” Hopkins inquired. “Your trip to England,” Early said. “The President just announced it at his press conference.” While Hopkins had been hard at work on President Roosevelt’s State of the Union address, the President had been briefing reporters on Harry Hopkins’ trip, telling them that he, “was asking Harry Hopkins to go over [to England] as [his] personal representative,” and he would leave “very soon.” Roosevelt emphasized that Hopkins was not traveling to the United Kingdom with an official title, nor with any special mission or powers. Instead, according to Hopkins’ biographer David L. Roll, “Hopkins was given at least two specific assignments. First, he was to assess whether the British people and their government, with aid from the United States, could withstand the attacks from air and sea and eventually prevail over the Germans. Second, without committing the nation to anything specific, especially while the lend-lease legislation was pending in Congress, Hopkins was to convey to Churchill the sense that America would support Great Britain as it fought the Nazis.”2 Roosevelt, downplaying the importance of Hopkins’ mission, further explained that, “He’s just going over to say ‘How do you do?’ to a lot of my friends and would be talking “to Churchill like an Iowa farmer.”3 Hopkins’ was going to get his adventure in England after all! While he had no official title nor special authority, Hopkins’ journey to London would nevertheless play a crucial role in laying the foundation upon which Churchill and Roosevelt’s relationship could be built in the tumultuous years that lay ahead.

Over the next twenty-four hours, Hopkins attended a number of prearranged meetings meant to help prepare him for meeting with Winston Churchill. On the afternoon of January 3, 1941, he met with Secretary of State Cordell Hull for forty-five minutes. Then, he had a “long talk” with the well-connected Frenchmen, Jean Monet, who had been working in the United States on the behalf of France when his nation surrendered to the Nazis in the summer of 1940, and was now temporarily assigned to the British Purchasing Commission. Monet told Hopkins that he should not waste time on the different ministers of the British government, explaining to him that, “Churchill is the British War Cabinet and no one else matters.”4 Monet’s suggestion irritated Hopkins who replied, “I suppose Churchill is convinced he is the greatest man in the world!”5 Felix Frankfurter, who had arranged the meeting with Monet, cautioned Hopkins, “Harry, if you’re going to London with that chip on your shoulder, like a damned little small town chauvinist, you may as well cancel your passage right now.”6 Nevertheless, Hopkins maintained his deep reservations about the British prime minister. The next day, Hopkins met with Neville Butler, the acting head of the British Embassy in Washington. He explained to Butler that the president wanted him to, “obtain from Churchill and others “pretty precise” estimates of the types and number of ships, aircraft, munitions, and other war materials needed by the British.”7 “The President’s chief desire,” Hopkins explained, was to convey to the British that, as a matter of self interest, the United States intends to provide all of the armaments needed to “enable Great Britain to beat Hitler.”8

With this information in hand, Butler and others alerted Churchill and his ministers about Hopkins’ impending visit to London. Felix Frankfurter enlisted the help of the Australian ambassador, Richard Casey, who informed Churchill that Hopkins was coming to London as Roosevelt’s “alter ego” and should be treated with the greatest candor, respect, and goodwill, as if he were Roosevelt himself. According to Roll, Frankfurter also told Casey that, “Hopkins was under the impression that Churchill did not regard Roosevelt as a great statesman and that therefore the prime minister would be well advised to disabuse Hopkins of this impression and to repeatedly indicate that he had the highest esteem for the president.”9 Therefore, while Hopkins’ mission was neither an official state visit nor imbued with any of the customary pomp and circumstance typical of diplomatic missions, he would play a crucial role in shaping how Roosevelt and Churchill perceived each other. He could convince the president that the prime minister respected and admired him, thus helping to foster the two leaders’ relationship before they had even met. Additionally, he could assure Churchill that FDR stood behind him in his struggle against the Nazis, thus assuring him that Great Britain was not alone after all. In this light, Hopkins’ “adventure” to London takes on a more significant meaning. He was President Roosevelt’s man; a broker of alliances; a mediator between two extraordinary leaders; an emissary of salvation; a representative of an awakening giant.

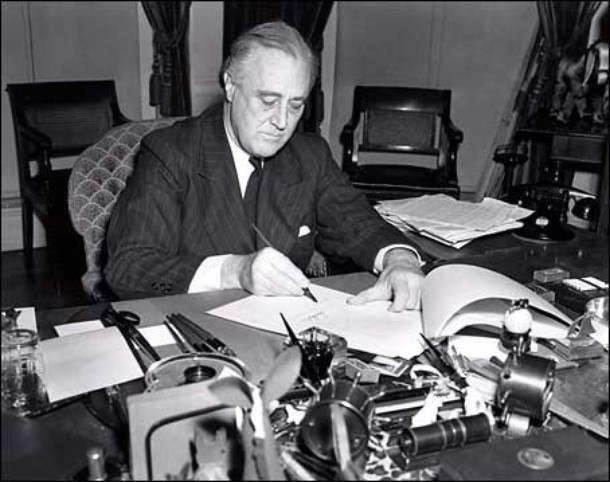

On the evening of January 4, 1941, Hopkins met with President Roosevelt one last time before departing for London. Roosevelt bestowed upon him a letter of authorization which read:

Reposing special faith and confidence in you, I am asking you to proceed at your early convivence to Great Britain, there to act as my personal representative. I am also asking you to convey a communication in this sense to His Majesty King George VI. You will, of course, communicate to this Government any matters which may come to your attention in the performance of your mission which you may feel will serve the best interest of the United States. With all best wishes for the success of your mission,

I am, Very sincerely yours,

Franklin D. Roosevelt”10

The president also gave him a letter addressed to the King of the United Kingdom, his majesty King George VI, which read:

YOUR MAJESTY:

I have designated the Honourable Harry L. Hopkins as my personal representative on a special mission to Great Britain. Mr. Hopkins is a very good friend of mine in whom I repose the utmost confidence. I am asking him to convey to you and to Her Majesty the Queen my cordial greetings and sincere hope that his mission may advance the common ideals of our two nations.

Cordially your friend,

Franklin D. Roosevelt11

With these two letters in hand, Hopkins departed on the first leg of his voyage to London. First, he boarded a train bound for New York City where he met former Ambassador Joe Kennedy. He implored Kennedy to support the passage of the Lend Lease bill to no avail, a foreshadowing of the bitter fight set to unfold in the U.S. Congress in the coming weeks. From New York, Hopkins boarded a Pan-American clipper destined for The Bahamas and The Azores. From there, Hopkins would fly to Lisbon, Portugal before finally boarding a British Overseas Airways flight to Poole Bay on England’s south coast. Finally, from Poole Bay, Hopkins would be taken by car to London. However, London was no ordinary city. Indeed, these were not ordinary times! The great city, this imperial capital, was under siege by a skilled and fearsome foe shrouded more often than not in darkness: the German Luftwaffe. Hopkins was entering a new world; a world whose buildings and streets were warped and ruined by fire and wanton destruction and whose people were scarred by war and suffering. This was London during The Blitz!12

In 1939, London was the greatest city in the world. The sheer size of its population, nearly 8.2 million people in Greater London alone, denoted its place at the center of world diplomacy, commerce, trade, and finance. According to Philip Ziegler, “the wealth of the world flowed through the city of London, that tiny, congested area between the docks and East End and the affluent West End. The stock exchange, the banks, the insurance companies, the heart of the intricate web by which money travelled freely to every part of the globe, was to be found in ‘the square mile’ of narrow, crooked streets and…mainly undistinguished buildings.”13 Aside from being the center of world commerce, trade, and finance, London was also the capital of the British Empire. The various officials who oversaw the administration of the vast dominions of the empire lived and worked in the City of London. The MPs who legislated on behalf of millions and millions of Britons, and who decided the fates of even more millions of colonial peoples, did so as well. If London was the epicenter of an empire, then it was also the beating heart and artery system of the United Kingdom. No other city in the island nation matched London’s population, capacity of trade, or manufacturing. Ziegler explains that, “London was not a, it was the metropolis; Edinburgh (Scotland) and Cardiff (Wales) might think of themselves as capitals, but in any significant sense, they did not stand comparison. London handled more tonnage than any other port in the world; a quarter of the country’s imports passed through the Port of London, nearly twice the amount handled by the second port, Liverpool. Few thought of London as a manufacturing city, yet the value of its factories’ output was larger than that of the industrial cities of the Midlands or the North.”14 Additionally, London, with its elaborate system of roads and rails, connected the various cities, ports, and towns across the kingdom, thus making the great city the focal point of the nation. Finally, London, as home to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, was a royal capital. It was the seat of a monarchy that, unlike many other monarchies of Europe, had withstood every trial and tribulation of the tumultuous 20th century.15 However, the “gathering storm” over Europe in the mid-to-late 1930s spelled trouble for the magnificent city. Indeed, it would not be long before London, and people all over the United Kingdom, would face a trial by fire.

The outbreak of war in Europe in the summer of 1939, and the subsequent fall of France in May of 1940, created a serious crisis for the City of London and its people. Historian Philip Ziegler explains that, “To those concerned with such matters, London was special in another way: it was a prime target, the prime target, for aerial attack.” London’s size made it an easy target for enemy bombers that could simply drop their bombs on the city’s vast expanse. Its importance to the economic life of the nation also made London a prime target for enemy aircraft. Ziegler says that, “A blow at London would be a blow simultaneously to the brain and to the heart, which might leave the limbs twitching for a while but would effectively destroy the capacity to resist…London in 1939 was not merely the greatest city in the world; its rulers believed it to be the most threatened and the most vulnerable.”16 A successful attack on London could cripple the entire nation’s war effort in one fell swoop by severing communication and transportation networks and undermining the country’s industrial, commercial, and financial base. Such was the risk of being the heart, brain, and arteries of the nation.

Fears about London’s vulnerability proved to be justified by the late summer of 1940. Much about life in London changed in the immediate days and months after Great Britain’s declaration of war on September 3, 1939. The very landscape of the city transformed almost overnight. Sandbags and freshly painted yellow postboxes, which could detect the presence of poisonous gases in the air, became commonplace sights for Londoners during the first days of war. People’s daily lives changed as well. Gas masks, mass evacuations, especially of children, and a mandatory nighttime blackout became part of a new normal for the citizens of the great metropolis in the first weeks of war. Despite the myriad changes brought upon London and Londoners’ daily lives by the onset of hostilities, the city was initially spared from serious aerial attacks. In fact, the first months of World War II in Europe were marked by German air raids on British airbases and industrial targets as well as shipping in the English channel. The country’s civilian population was left largely unmolested by the forces of the Luftwaffe. By the summer of 1940, an intense war was raging in the skies over Britain as the thinly spread Royal Airforce (RAF) fought intrepidly to protect Great Britain and its people. Wave after wave of German bombers came, but the RAF retained command of the skies. The Luftwaffe’s inability to break the Royal Air Force partially contributed to a change in bombing targets towards the end of that summer. Whereas before, the Luftwaffe had targeted strategic locations such as airbases and industrial complexes, it was now going to target innocent civilians.17

September 7, 1940 dawned warm and still. A blue sky rose above a rising haze. By the afternoon temperatures were in the low 90s, an unusually warm day for London. Londoners floated into Hyde Park and lounged on chairs set out beside the Serpentine Lake. London’s West-End theatres hosted twenty-four productions of plays, such as Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Despite bombing raids the previous month, Londoners had slumped “into a dream of invulnerability, punctuated now and then by false alerts whose once-terrifying novelty was muted by the failure of bombers to appear.”18 Then, the Luftwaffe came. The bombers arrived in three waves, the first containing nearly 1,000 aircraft: 348 bombers and 617 fighters. The citizens of London and the surrounding villages could hear and see the enemy aircraft approaching. Writer Virginia Cowles, and her friend Anne, were staying with British press baron Esmond Harmsworth in the village of Mere-worth, about thirty miles southeast of central London. Cowles recalled that, “At first we couldn’t see anything, but soon the noise had grown into a deep, full roar, like the faraway thunder of a giant waterfall.”19 Cowles and Anne counted more than 150 planes in the sky headed directly for London. The bombers were flying in formation, with escort fighters surrounding them as a protective shield. She later wrote that, “We lay in the grass, our eyes strained towards the sky; we made out a batch of tiny white specks, like clouds of insects moving northwest in the direction of the capital.”20 “Poor London,” her friend said.21 Poor London indeed!

By the next morning, September 8, 1940, three waves of German bombers had swept over London. The night was one filled with fire, smoke, death, and a great many firsts for all Londoners. Anyone who dared step outside saw a glowing red sky. They saw too the brave firefighters struggling against the blazes spread out across the city. The soon to be familiar smell of cordite after a bomb explosion permeated the air. The sounds of broken glass being swept up from the streets also filled Londoners’ ears. Many residents also heard bombs fall for the first time during the nighttime raids. Phyllis Warner, a school teacher, described in her journal the sound of a bomb falling on the buildings below as, “an appalling shriek like a train whistle growing nearer and nearer, and then a sickening crash reverberating through the earth.”22 In their totality, the air raids of September 7, 1940, forever after nicknamed “Black Saturday,” killed 400 Londoners and injured four times as many others. “Black Saturday” also inaugurated the era of “The Blitz,” a period of eight months during which London, and other British cities and towns, were subjected to persistent and deadly attacks from the air. The Germans used such weapons as incendiaries, high-explosive (HE) bombs, and parachute mines in an attempt to, “terrorize the British people into surrender by ravaging their cities, industries and population centres from the air.”23 By the time Harry Hopkins arrived in London, the great city had endured over five months of increasingly brutal attacks. Despite the grim situation, however, Britain’s people, including its prime minister Winston Churchill, remained resolute in the face of the Nazi menace that was threatening them from the air.

Hopkins arrived at Poole Bay on January 9, 1941. Churchill had sent his private secretary and close friend, Brendan Bracken, to the airport to greet FDR’s man and escort him to London. Bracken found a pale and skeletal looking Hopkins laid back and seated on the airplane in a state of collapse. Chronically in poor health, Hopkins was so exhausted that he could not unbuckle his seatbelt. After some time, however, he was able to rally and board a specially reserved train that would take him to London. His train ride along the English coast gave Hopkins his first glimpses of life during The Blitz. He saw firsthand the damage done to the coastal towns of Poole, Southampton, and Bournemouth. As his train car wound by the fields in the English countryside, Hopkins asked Bracken, “Are you going to let Hitler take these fields from you?” “No,” Bracken replied.24 Furthermore, Hopkins’ train passed over tracks that had recently been bombed by hundreds of incendiaries. When his train arrived at Waterloo Station at 7:00pm, Hopkins found Herschel Johnson, charge d’affaires at the American Embassy, waiting for him with his driver. Together, the two men were driven through the blacked-out streets of London to Claridge’s Hotel, Hopkins’ home for the duration of his stay in London.25That night, with antiaircraft guns blazing in Hyde Park, Hopkins and Johnson ate dinner together at Claridge’s. Johnson confided in Hopkins that, prior to his arrival, he had doubted whether the United States’ leaders fully comprehended the dire situation in Britain. For months, Johnson had received nothing from home but strict instructions to maintain U.S. neutrality and to say nothing that could arouse isolationist criticism at home. However, Johnson sensed a change in the winds when he conversed with Hopkins at Claridge’s. He later told Sherwood that, “I was immediately heartened by the sincerity and the intensity of Harry Hopkins’ determination to gain further knowledge of Britain’s needs and of finding a way to fill them. Some other Americans who had come to London devoted themselves to investigations to determine if the British really needed the things they were asking for. Harry wanted to find out if they were asking for enough to see them through. He made it perfectly clear that he did not know how or where he was going to begin, or what his methods would be, but he knew precisely what he was there for. He made me feel that the first real assurance of hope had at last come—and he acted on the British like a galvanic needle.”26 It seemed that Harry Hopkins had indeed brought salvation to London and its people!

The next day, January 10, 1941, Hopkins arrived at No. 10 Downing Street, the official residence of the prime minister of the United Kingdom. Hopkins walked into the residence looking fragile, wary, and sallow complected. A large overcoat added to Hopkins’ dreary appearance. Pug Ismay, chief military assistant to Winston Churchill, wrote of Hopkins that, “He was so unlike one’s picture of a distinguished envoy as it was possible to be,” he elaborated further, “He was deplorably untidy; his clothes looked as though he was in the habit of sleeping in them, and his hat as though he made a point of sitting on it. He seemed so ill and frail that a puff of wind would blow him away.”27 Brendan Bracken, who was there to greet him, gave Hopkins a tour of the famous residence. Hopkins later wrote in a memo to Roosevelt that, “Number 10 Downing is a bit down at the heels because the Treasury next door has been bombed more than a bit.”28 Bomb damage scarred the house. Most of the windows had been blown out, and workers rushed to and fro repairing them in kind. After the tour had concluded, Bracken escorted Hopkins to the newly constructed armoured dining room located in the basement, where he poured him a glass of sherry to hold him over until the prime minister arrived. Eventually, Winston Churchill appeared.29 When relating his initial meeting with Churchill to Roosevelt, Hopkins later wrote, “A rotund-smiling red-faced, gentleman appeared-extended a fat but never the less convincing hand and wished me welcome to England. A short black coat-striped trousers-a clear eye and mushy voice was the impression of England’s leader as he showed me with obvious pride the photograph of his beautiful daughter-in-law and grandchild.”30 Over lunch, Hopkins and Churchill discussed the upcoming meeting between the prime minister and the president. Hopkins relayed how anxious the president was to meet Churchill, and the British leader responded in kind. Never one to mince words, Hopkins then turned to the issue of the prime minister’s perceived dislike of Roosevelt, “I told him there was a feeling in some quarters that he, Churchill, did not like America, Americans or Roosevelt,” he later wrote to FDR.31 Upon hearing such accusations, Churchill immediately went on the defensive, blasting former ambassador Joseph Kennedy for crafting such a misleading picture of his feelings towards the president and the American people. He then produced for Hopkins the telegram message he had sent Roosevelt upon his reelection the previous fall as proof of his cordial feelings towards the American president—a telegram that had apparently gone unanswered.32

Hopkins, sufficiently convinced of Churchill’s genuine good will towards the president, then briefed him on his mission to London. “I told of my mission—he seemed pleased—and several times assured me that he would make every detail of information and opinion available to me and hoped that I would not leave England until I was fully satisfied of the exact state of England’s need and the urgent necessity of the exact material assistance Britain requires to win the war,” he explained to Roosevelt.33 After Hopkins had finished, Churchill took over the conversation. He regaled Hopkins with a sweeping narrative of the war up to 1941. He moved with his customary eloquence and rhetorical power from the fall of France to the situation unfolding in Greece. Churchill even ranged into the topic of poisonous gas, telling Hopkins that the British would only use such a weapon if the Germans used it first. He also took the opportunity to discuss Britain’s growing might in the air, telling Hopkins that he expected the ratio between German and British bombers to thin in the coming weeks, and that he looked forward to achieving aerial supremacy with American help. After lunch, Churchill took Hopkins to the British cabinet room and showed him a map of British convoy routes, complete with German bomber interception paths.34 According to Jock Colville, a British civil servant and friend of the Churchill family, Hopkins and Churchill, “were so impressed with each other that their tete-a-tete did not break up till nearly 4:00.”35 By the time Hopkins left for Claridge’s, it was getting dark, and a full moon was rising above the blacked-out city. Hopkins’s initial meeting with Churchill not only dispelled the rumors about the prime minister’s attitude towards Roosevelt, but it also inaugurated the first stages of a deep and lasting friendship between the two men, a friendship that would last until Hopkins’ death in 1946.

For the next two weeks, Hopkins and Churchill were inseparable. Hopkins later estimated that he spent twelve of fourteen nights with the prime minister during the first two weeks of his stay. Hopkins even accompanied Churchill on his weekly sojourns in the British countryside during the weekend of January 11, 1941. On this particular weekend, Churchill was staying at Ditchley Park, a lavish country estate owned by Ronald and Nancy Tree, in lieu of his usual Chequers home, which he had forsaken for this weekend due to its conspicuousness in a full moon. There was nothing about Ditchley Park that was not lavish. Jock Colville wrote of Ditchley that, “Dinner at Ditchley takes place in a magnificent setting. The only illumination was candlelight, with candles mounted on the walls and in a large chandelier overhead. The table is not over-decorated: four gilt candle sticks with tall yellow tapers and a single gilt cup in the center.” Colville went further, praising the bountiful food, judging it, “in keeping with the surroundings.”36 This must have indeed been a strange outing for the frail Hopkins; an Iowa-raised rural man who now found himself inundated in the traditions and illustrious settings of the British aristocracy. Despite the unfamiliar surroundings, Hopkins continued deepening his relationship with Churchill and his inner circle. While at dinner on Saturday January 11, Hopkins praised Churchill for his speeches and even related how President Roosevelt had once played one of them during a cabinet meeting. After dinner, when the women had departed and Churchill’s wits had been softened by his favorite combination of brandy and cigars, he launched into another one of his sweeping oratories about the war. This time he elaborated on Britain’s war aims saying, “We seek no treasure, we seek no territorial gains, we seek only the right of man to be free; we seek his right to worship his God, lead his life in his own way, secure from prosecution. As the humble laborer returns from his work when the day is done, and sees the smoke curling upwards from his cottage home in the serene evening sky, we wish him to know that no rat-a-tat”–here Churchill paused and knocked loudly on the table–“of the secret police upon his door will disturb his leisure or interrupt his rest.”37 He went on, saying that the United Kingdom sought government by consent of the governed, freedom of speech, and equality for all people under the law. Churchill concluded, “But war aims other than these we have none.”38

Churchill turned to Hopkins and asked him, “What will the president say to all that?” Hopkins sat, contemplating his answer. His prolonged silence left those present on the edge of their seats. Finally, after some time, Hopkins replied, “Well, Mr. Prime Minister, I don’t think the President will give a dam’ for all that.” Churchill and his companions grew anxious as they waited to hear if Hopkins would finish with a more flattering appraisal of Churchill’s speech. Finally, he continued, “You see, we’re only interested in seeing that that God dam sonofabitch Hitler gets licked.”39 Those listening erupted in laughter, punctuated by a deep sense of relief. Hopkins was clearly sending a message to Churchill: the United States would stand with Great Britain as they fought the Nazis. It was clear also that Churchill was winning Hopkins over as well. On January 14, 1941 Hopkins wrote a lengthy letter to Roosevelt in which he praised Churchill and the British people, writing, “The people here are amazing from Churchill down and if courage alone can win-the result will be inevitable.” However, Hopkins also stressed the dire situation facing Britain and its people, writing, “But they need our help desperately and I am sure you will permit nothing to stand in the way.” In the same letter Hopkins, like others before him, stressed Churchill’s preeminence among the ministers of the British government, “Churchill is the government in every sense—he controls the grand strategy and often the details—labor trusts him—the army, navy, air force are behind him to a man…I cannot emphasize too strongly that he is the one and only person over here with whom you need to have a full meeting of minds.” Towards the end of his letter, Hopkins once again implored his president to help the British people, “This island needs our help now Mr. President with everything we can give them.”40 After Hopkins had finished penning his letter to Roosevelt, he left Claridge’s to join Churchill on his journey to Scotland. His adventure to Great Britain was about to take him to the far reaches of the kingdom!

As Hopkins was finishing his letter at Claridge’s, Churchill was preparing to embark on a journey to the natural harbor at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands to see the newly appointed British ambassador to the United States, Lord Halifax, off on the brand new battleship HMS King George V, which would carry the newly appointed diplomat to America. When he woke up that morning, Churchill was in the throws of a bronchial cough; he looked and sounded terrible. His wife, Clementine, begged him not to go to Scotland, as did his doctor Charles Wilson. However, they soon realized how futile their efforts were. Wilson suspected that Churchill just wanted to see the ships of the British Fleet moored at Scapa Flow. He would go to Scapa Flow come hell or high water! Hopkins was making the trip to see the fleet as well. The entire party, including Churchill, Clementine, Lord and Lady Halifax, Dr. Wilson, American military officer General Raymond Lee, Hopkins, and the various detectives and staff that looked after the prime minister, would travel on Churchill’s special train, complete with a lounge, dining car, a separate prime ministerial suite, and twenty-four first class cabins. That night, while enroute to Scapa Flow, Hopkins dined with Churchill once more. Despite Churchill’s bronchitis, the two men talked until 2:00am. General Lee recalled of Churchill that, “He was enjoying himself and with his vast knowledge of history, his power of expression and his huge energy, putting up a show for Hopkins. Hopkins is really the first representative of the president he has had a fair go at. I’m sure he never confided in or even cared for [Joseph] Kennedy.”41

The next morning Churchill and his party awoke to the news that a derailment on the tracks to Scapa Flow had stalled their train outside the Scottish town of Thurso. The weather was horrid! It was freezing cold and snow fell to the ground as a blizzard raged around the stalled locomotive. With the weather so terrible, Clementine and Dr. Wilson urged Churchill to abort his trip to see the fleet. However, Churchill continued on stubbornly, climbing into a car waiting besides the train tracks and vowing that he was going to Scapa Flow come what may. With Churchill’s indomitable will having decided the issue, Hopkins and the other members of the company climbed into their own waiting vehicles to finish the rest of the trip to the naval base. From the tracks outside Thurso, Churchill and his party were driven to the small port of Scrabster. Here the party splintered as Churchill, Clementine, Hopkins Lord and Lady Halifax, and Pug Ismay boarded the British destroy, HMS Napier. The small vessel escorted them through the swelling waves, snow flurries, and anti submarine nets just outside the main harbor. The view from inside of Scapa Flow was breathtaking. The sun peaked out from behind the clouds casting bright light down upon the snowy hilltops surrounding the harbor and on the castles of steel moored within. Pug Ismay was so awed by the tremendous sight of the great ships in the harbor that he decided he wanted to share the sights with Harry Hopkins. According to Ismay, “I wanted Harry to see the might, majesty, dominion, and power of the British Empire in that setting and to realize that if anything untoward happened to these ships, the whole future of the world might be changed, not only for Britain, but ultimately for the United States as well.”42 Ismay found Hopkins shaking, exhausted from the cold. He gave the feeble man one of his own sweaters and a pair of boots lined with fur. However, Ismay could do nothing to convince Hopkins to venture out on deck. Instead, Hopkins sought out further shelter from the wind and the cold. He found a spot that seemed nice and sat down. Alas, the tired man was promptly advised to move because he had taken shelter next to a depth-charge.43

After Churchill had seen off Lord and Lady Halifax and General Raymond on HMS King George V, he and his party retired for the night onboard the old and odd-looking battleship, HMS Nelson. The next morning brought even worse weather than the day before, making safe travel between ships extremely dangerous. Churchill’s party was set to depart Scapa Flow for their train that morning. The entire company left HMS Nelson onboard the admiral’s barge bound for HMS Napier. The barge and the little destroyer pitched and rolled in the heavy waves as Churchill and the others made their ascent via ladder from one ship to the other. Churchill, talking the whole way, ascended first, his weight straining the rungs of the ladder so much he cracked a step. While others, such as Pug Ismay, avoided the step which Churchill had cracked, Harry Hopkins did not. Instead, the already exhausted and fragile Hopkins broke the step entirely and began to fall towards the barge and the angry sea below. Luckily, two British seamen caught the poor man by his shoulders just above the barge. Watching the episode from above, Churchill shouted, “I shouldn’t stay there too long, Harry; when two ships are close together in a rough sea, you are liable to get hurt.”44 Fortunately, Hopkins escaped the incident unharmed, and Churchill and his companions proceeded to their train and departed for Glasgow, Scotland. Hopkins’ journey to Scapa Flow was an adventure indeed! Maybe even too much of an adventure for the sickly man! However, his appreciation for Churchill and the British people had not dimmed; if anything it had grown even stronger. It was while he was in Scotland that Hopkins showed Churchill just how much he had grown to appreciate him and the valiant fight he and his nation were waging against Hitler.45

On the way back to London, Churchill’s train stopped in Glasgow, Scotland where he reviewed brigades of civilian volunteers such as firefighters, members of the Red Cross, and those working in the Air Raid Precautions service (ARP) and the Women’s Voluntary Service. Churchill would stop to introduce Harry Hopkins as he reviewed the members of each organization. This proved to be too much for Hopkins, who hid among the crowds of spectators gathered to see Churchill, but to no avail. Each time he hid, Churchill would coax him out of the crowds, shouting, “Harry, Harry, where are you?”46 Next, Hopkins, Churchill, and company moved to the Station Hotel where they ate dinner with journalist and member of Parliament, Tom Johnston. While at dinner, Dr. Charles Wilson sat beside Hopkins. He was struck by his disheveled and unkempt appearance; he looked worse than he ever had before. Invariably, the time for speeches arrived. When Hopkins’ opportunity to speak came, he stood and began his speech by making a few jokes about the English Constitution and Churchill. Then, he turned to Churchill and said, “I suppose you wish to know what I am going to say to President Roosevelt on my return.” Indeed, this was the moment Churchill had been waiting for; the fate of his entire nation hung on Hopkins’ next words. “Well,” Hopkins continued, “I’m going to quote you one verse from that Book of Books in the truth of which Mr. Johnston’s mother and my own Scottish mother were brought up”—Hopkins lowered his voice to a whisper and quoting from the Book of Ruth said, “Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge; thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.” Then, Hopkins added his own personal touch to the beautiful verse softly saying, “Even to the end.”47 Churchill broke down in tears. Everyone present understood the significance of the words Hopkins had uttered. Dr. Charles Wilson wrote of the moment that, “Even to us the words seemed like a rope thrown to a drowning man.”48 President Roosevelt’s man had spoken, but his speech was tinged by his partiality to Churchill and his lived experience of The Blitz. In truth, many people in the United States held deep reservations about assisting the British in a “European” war. This great divide within American public opinion was typified by the ongoing battle in the U.S. Congress over the Lend Lease Act.

In December 1940, while recuperating aboard the warship USS Tuscaloosa, President Franklin Roosevelt received an urgent and lengthy letter from Winston Churchill. In it the prime minister briefed the president on the course of the war up to that point, swiftly covering topics such as the state of the Vichy government in France and Britain’s material needs regarding weapons, munitions, and other war products. Also, Churchill candidly told Roosevelt about Britain’s dire financial situation writing:

The moment approaches when we shall no longer be able to pay cash for shipping and other supplies. While we will do our utmost, and shrink from no proper sacrifice to make payments across the Exchange, I believe you will agree that it would be wrong in principle and mutually disadvantageous in effect if at the height of this struggle Great Britain were to be divested of all saleable assets, so that after the victory was won with our blood, civilisation saved, and the time gained for the United States to be fully armed against all eventualities, we should stand stripped to the bone.49

With Great Britain’s financial assets abroad thinning, serious concerns were emerging about the embattled nation’s ability to continue paying for war materials ordered in the United States. Roosevelt pondered Churchill’s letter for two days. Harry Hopkins later told him that the president, “read and reread the letter, sitting alone on the deck in a place protected from the wind.”50 Then, on the evening of December 11, Roosevelt and Hopkins conceived the basic idea for a bill that would provide the British with the material aid they so desperately needed without straining the country’s finances; the United States would loan Great Britain all the material it needed, which Britain would then pay for when the war was over. However, the president faced two serious problems: getting the future bill passed in Congress and justifying it to the American people. Nevertheless, over the coming weeks, Roosevelt and Hopkins poured hours into their idea, which would later be called “Lend Lease.” On December 17, 1940, Roosevelt addressed the bill at a press conference saying:

“Now, what I am trying to do is eliminate the dollar sign. That is something brand new in the thoughts of everybody in this room, I think—get rid of the silly, foolish old dollar sign. Well, let me give you an illustration. Suppose my neighbor’s home catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose four or five hundred feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him put out the fire. Now what do I do? I don’t say to him, “Neighbor, my garden hose cost me fifteen dollars; you have to pay me fifteen dollars for it.” No! I don’t want fifteen dollars. I want my garden hose after the fire is over.”51

Through Lend Lease, Roosevelt hoped to nullify the all powerful dollar sign. His only priority was helping Great Britain win the war by providing them with any and all material they required in order to beat Hitler. The press conference also demonstrates how much Hopkins’ and Roosevelt’s idea had evolved in the short interval between its inception and his December 17th press conference. Roosevelt had eliminated the idea of payment all together. Instead, Great Britain would simply return whatever material they’d used during the war after the cessation of hostilities. In selling the idea to the American people, Roosevelt enlisted the help of Harry Hopkins, Robert Sherwood, and Samuel Rosenman. Together, the three men prepared draft after draft of what would become the “arsenal of democracy” fireside chat.52 In the final version of the speech, broadcast on December 29, 1940, Hopkins and his fellow writers sold Lend Lease as a matter of American national security. They argued that the recently signed Tripartite Pact between Italy, Germany, and Japan necessitated this new bill. “Never before since Jamestown and Plymouth Rock has our American civilization been in such danger as now…We must be the great arsenal of democracy,” FDR declared in his address to the American people.53 Roosevelt’s speech had a profound impact on American public opinion. According to a Gallup poll, by January 1941, 68 percent of Americans favored Lend Lease.54 Even though over two-thirds of the country was behind him, Roosevelt would still face a fierce battle in the U.S. Congress. Indeed, from January to February 1941, the fate of Lend Lease was still very much in doubt as the two chambers of the Congress debated the bill in their stead. During the floor debate in the U.S. Senate, Republican Senator Hiram Johnson declared that, “This bill is war.”55 However, for all their rhetoric and zeal, Lend Lease’s opponents were unable to stop the bill from becoming law. Finally, on March 8, 1941, the Senate passed the bill with 60 votes for and 31 votes against the Lend Lease Act. Three days later, after the House of Representatives’ final vote on the bill, Hopkins left a telephone message for Churchill giving him the good news. Churchill replied with a cable, “The strain has been serious so I thank God for your news.” Through Lend Lease, the United States was able to pour its bountiful resources into a beleaguered nation and hopefully begin to turn the tide of war.56

Harry Hopkins was still in the United Kingdom as the battle over Lend Lease raged in the U.S. Congress. In fact, Hopkins did not leave Great Britain until February 8, 1941, the day the bill passed its first vote in the U.S. House of Representatives. On the day of his departure, Hopkins visited Churchill at Chequers and left him a note which read:

My dear Prime Minister,

I shall never forget these days with you—your supreme confidence and will to victory—Britain I have ever liked—I like it the more. As I leave for America tonight I wish you great luck—confusion to your enemies—victory for Britain.57

Victory would come in time. Nevertheless, darker days lay ahead for Great Britain and for the United States. However, Hopkins’ journey to England had laid the foundation for Roosevelt and Churchill’s relationship in the years that followed his initial visit. Furthermore, everyone who met and interacted with Hopkins grew to love him. From Winston Churchill to the staff that looked after him at Claridge’s Hotel, the frail man had endeared himself to all those he had met.58 Perhaps Churchill paid the best tribute to his friend when he wrote in his memoirs:

“Thus I met Harry Hopkins, that extraordinary man, who played, and was to play, a sometimes decisive part in the whole movement of the war. His was a soul that flamed out of a frail and failing body. He was a crumbling lighthouse from which there shone the beams that led great fleets to harbour.”59

Hopkins’ role in the war was one of profound importance. He gave hope, whether or not it was his to give, to an entire nation that they might be saved at last. Hopkins, as frail and sick as he was, also helped bring together the great leaders of the Allied powers, and thus helped see World War II through to its victorious conclusion. He was indeed an emissary of salvation for millions of people.

- Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 230. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 79. ↵

- President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 79. ↵

- Jean Monet, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 79. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 79. ↵

- Felix Frankfurter, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 80. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 80. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 80. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 80. ↵

- FDR to HH, January 4, 1941, found in, Robert E. Sherwood, The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins: An Intimate History (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1948), 233. ↵

- FDR letter to His Majesty of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, January 4, 1941, found in, Robert E. Sherwood, The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins: An Intimate History (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1948), 233. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 81. ↵

- Philip Ziegler, London at War, 1939-1945, 1st American ed. (New York: Knopf, 1995), 4-5. ↵

- Philip Ziegler, London at War, 1939-1945, 1st American ed (New York: Knopf, 1995), 4-5. ↵

- Philip Ziegler, London at War, 1939-1945, 1st American ed (New York: Knopf, 1995), 6. ↵

- Philip Ziegler, London at War, 1939-1945, 1st American ed (New York: Knopf, 1995), 6. ↵

- Alan Jeffreys, London at War 1939-1945: A Nation’s Capital Survives, 1st edition (Imperial War Museums, 2018), 12-21. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 209. ↵

- Virginia Cowles, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 211. ↵

- Virginia Cowles, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 211. ↵

- Anne, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 211. ↵

- Phyllis Warner, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 214. ↵

- Alan Jeffreys, London at War 1939-1945: A Nation’s Capital Survives, 1st edition (Imperial War Museums, 2018), 37-39. ↵

- Brendan Bracken, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 81. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 81-82. ↵

- Herschel Johnson, quoted in, Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 235-236. ↵

- Pug Ismay, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 346. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 347. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 346-347. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 238. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 238. ↵

- Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 238. ↵

- Harry Hopkins quoted in, Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 238. ↵

- Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 239. ↵

- Jock Colville, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 347. ↵

- Jock Colville, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 350. ↵

- Winston Churchill, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 351. ↵

- Winston Churchill, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 351. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 351-352. ↵

- HH to FDR on Claridge’s Hotel stationery, January 14, 1941, found in, Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins An Intimate History, 1st edition (New York, NY: Harper Brothers, 1948), 243-244. ↵

- General Raymond Lee, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 357. ↵

- Pug Ismay, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 360. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 357-361. ↵

- Winston Churchill, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 362. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 360-362. ↵

- Winston Churchill, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 362. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 362-363. ↵

- Dr. Charles Wilson, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 363. ↵

- Winston Churchill to President Franklin Roosevelt, December 8, 1940, in Winston S. Churchill, Their Finest Hour, The Second World War (Boston: The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1949), 566. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 75. ↵

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 76. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 76. ↵

- “FDR Fireside Chat 16: On the Arsenal of Democracy,” video file, 6:39, YouTube, posted by MCamericanpresident, November 10, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7BKvlobfBY&ab_channel=PeriscopeFilm. ↵

- David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 76. ↵

- Senator Hiram Johnson, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 99. ↵

- Winston Churchill, quoted in, David L. Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), 100. ↵

- Harry Hopkins, quoted in, Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 368. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, First Edition (New York: Crown, 2020), 364-365, 368. ↵

- Winston S. Churchill, The Grand Alliance (The Second World War) Volume Three, (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950), 23. ↵

45 comments

Alexa Casares

I have never heard about Harry Hopkins and reading this article was so easy and intriguing! Definitely enjoyed all the information relayed!

Andrick Ferrer

I think Christopher Hohman does a great job in emphasizing the role and influence of Harry Hopkins in the second world war. One that many of us, including me, were unaware of. It does not take much effort to notice that this article is both informative and well researched. Although the article may be considered too long for some, to others like me it felt like it was too interesting to even worry about that. Lastly, the use of quotes from historical figures and the pictures of these added a significant amount of attention to the reading for the audience. A very well-written article all throughout.

Veronica Lopez

I found this article quite interesting. I also found this article to be very informational. It can help students or people to learn more about President Roosevelt, President Churchill and Harry Hopkins. I found it really cool how Roosevelt’s priority was helping Great Britain win the war by proving them with whatever they needed, in order to beat Hitler. I thought that was not necessary of the President but quite charming in its own way.

Andrew Molina

This article was so well written, this was such a cool read. It was riddled everywhere with cool facts and incredible information of the topic. The author went above and beyond to show us the links and measures Hopkins went. It’s so cool to see him as that middle man in a time of absolute chaos in the world. The amount of detail and specification is incredible in this article, I’ve never seen such a well worded article, especially for one of my favorite subjects, “WW2”, this was an absolute stand up job, beyond well done.

Amelie Rivas-Berlanga

I loved this article! A great introduction that really reels the reader in. I had never heard of Harry Hopkins before, this article did a great job at introducing me to who he was. To see the impact that Hopkins had on US/ International politics and Government is really amazing. The images and descriptions throughout the article were constructed amazingly! This article is clearly well researched and thought out. Well done!

Natalia Ramirez

This was a very interesting article to read about. It was very descriptive and had me engaged the entire time. I honestly did not know much about this topic, but I’ve definitely gained a lot of knowledge after reading this article. You provided a lot of sources and it shows in the article how much research you did. Great job!

Anthony Dinh

I don’t know too much about Hopkins, so his contributions to World War II is very fascinating. The Article was very well researched with a lot of information, as I am writing this comment I am still processing everything that I’ve read. The pictures also was very helpful to see what type of man he was and how he contributed and who he hanged around to see his contributions from personal view from images. Great Article!

Anissa Navarro

This article was so well written and structured. It had shared a lot of detail about something I apparently knew so little about. I had never known the in-depth story of Hopkins and how his small role did so much for the outcome of the war that we had. I do think the article was a little to long but it did do a great job of getting the whole story told.

Eliza Merrion

This article is very well written. I can tell a lot of research went into it and the outcome is very impressive. The article was very informative and educational for me. Learning about Harry Hopkins and President Roosevelt’s involvement in the war is very interesting. I learned a lot about Hopkins, Churchill, their relationship, and Hopkins’ purpose for going to London. I especially found the story of the Scapa Flow very interesting because I had not heard it before. Overall very good research and educational article.

Leon Martinez

I greatly enjoyed reading this article, at first, it seemed to me that it wasn’t quite clear to Hopkins what Roosevelt’s intentions were on sending him to London. During the meeting with the King and Queen along with Churchill, the meeting became apparent why. The war was imminent, after all, the meeting was successful. Thank you Mr. Hohman for this fantastic read, I look forward to reading more from you.