There are more monkeys here in Dayton than there are in the Chattanooga zoo,” George Rappleyea declared. He had just finished giving a rousing pro-evolution speech in front of the crowd at Robinson’s Drug Store when local barber Thurlow Reed decided to object. “You can’t call my ancestors monkeys!” Reed yelled before leaping from the crowd to attack Rappleyea. The two brawled in front of an interested audience before being pulled apart. Neither had injuries. Still, the crowd had no idea that the fight was all a performance. Rappleyea was not the fervent evolutionist he portrayed himself as and Reed was not a random angry onlooker. Rappleyea’s speech and fight were carefully constructed by him and several other entrepreneurs in Dayton, Tennessee. Reed himself was a collaborator recruited to stir up excitement. The purpose of the ruse was to gather interest for the indictment of a local teacher.1 The heinous crime the teacher stood accused of? The teaching of evolution. The purpose of this fight between Rappleyea and Reed? To bring a media circus to their little town of Dayton, Tennessee.

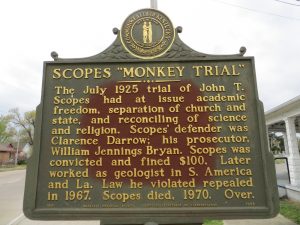

In 1925, the Tennessee General Assembly issued the Butler Act, declaring it illegal to teach evolution or any theory that denied the Bible’s story of Divine Creation.2 To be guilty of defying this law meant there could be a fine of upwards to $500 imposed. At the time this was a hefty amount as it was more than enough to buy a brand-new Model T Ford.3 The American Civil Liberties Union, or ACLU, found the Butler Act unjustified. The ACLU was recently formed and made up of New York’s most influential and progressive citizens. One of their core purposes was the safeguarding of free speech. It was because of this objection that the group decided to publish an ad in Tennessee.4

George Rappleyea was a local Dayton businessman when he saw the ACLU’s ad in the newspaper. The ad offered free legal defense for any teacher willing to stand against the law in court. While Rappleayea wasn’t much of an evolutionist, he was an opportunist. To him, this ad by the ACLU was an excellent opportunity to put Dayton on the map and revitalize their hurting economy. Rappleyea gathered local officials and businessmen at Robinson’s Drug Store to propose his plot. Once everyone was on board, they set about finding a teacher willing to test the law. Rappleyea approached local high school teacher John T. Scopes with this request. Scopes was mainly a math teacher and football coach. Occasionally, he subbed for other classes, like biology.5

At the time, Scopes was unsure if he had even taught about evolution. He did know he had taught out of the required textbook for the biology class Civic Biology by George W. Hunter. The textbook held only a few pages explaining evolution, along with some diagrams of an evolutionary tree.6 Scopes admitted it was possible he had discussed the topic in class. Despite Scopes’ uncertainty, he agreed to confess to the crime of teaching evolution. A warrant was then issued and Scopes was arrested. Rappleyea’s plan was working and interest for the case was beginning to gather, even outside of Dayton.

The nearby town of Chattanooga was especially interested. They too wanted a taste of the spotlight and the economic opportunities a potential case might bring. They began concocting their own plan to become the venue for the trial. To prevent this, Dayton officials rushed to put together a special grand jury session to indict Scopes. Several of the students Scopes had taught testified that he had indeed taught them evolutionism. Admittedly, they were coached by the defense lawyers. A few days after the staged fight, Scopes was indicted.7 Dayton had their criminal and now they needed a lawyer to defend him.

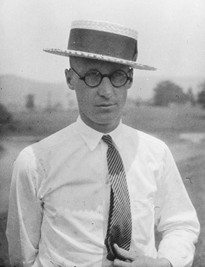

Clarence Darrow was the attorney who stepped forward to volunteer his services. He was one of the most well-known criminal defense lawyers at the time. He was also outspokenly anti-religious. Though he was on the cusp of retiring, he volunteered to represent Scopes after hearing that William Jennings Bryan would be prosecuting. Bryan, like Darrow, was also a well-known figure across the country. He had been a presidential candidate three times and was once Secretary of State for Woodrow Wilson. Bryan was a strict fundamentalist Christian and anti-evolutionist. After failing to gain political office, he turned to traveling the country and orating. He preached often about the danger of allowing certain intellectual ideas to leak into the school curriculum. He also attempted to pass and enforce laws based on religion. Darrow and Bryan had a history of butting heads, due to Bryan’s religious agenda. Though Darrow once voted Bryan for president, he publicly disdained him now.8 Pope of the peasants,” Darrow called him. 9

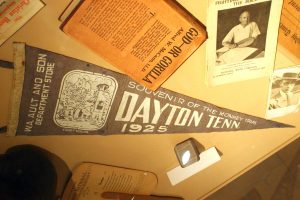

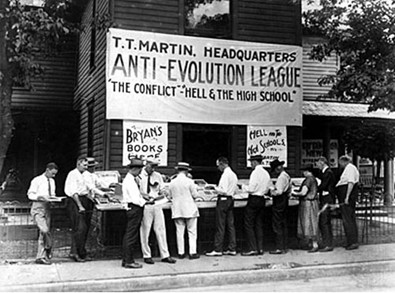

These two famous figures drew even more attention to the case. News reporters from all over flooded into Dayton and live radio coverage of the trial was set up by the Chicago station WGN.10 Spectators packed onto the courthouse’s lawn and vendors set themselves up to sell souvenirs of the event. Coins were sold with the image of a monkey wearing a hat engraved onto them. Actual monkeys were brought in to entertain and capitalize on the excitement of the so-called Monkey trial.11 The event had grown bigger than Rappleyea or the ACLU could have imagined. Scopes was quickly overshadowed by Darrow and Bryan and the fanfare they brought. The press was eager to document their ideological showdown between evolutionism and creationism.

Darrow intended to ridicule Bryan and his fundamentalist beliefs in front of the nation. With this purpose, he called Bryan to the stand for cross-examination, citing Bryan’s expertise in the Bible as the reason. The jurors were dismissed from the room despite the trial being by jury. Darrow then proceeded to interrogate Bryan on the literalism of the Bible. Bryan affirmed his belief that everything in the Bible was meant to be taken literally under Darrow’s questioning. He placed his complete blind trust in God for the things he could not make sense of. He was certain of all Biblical truths: the tower of Babel was the origin of different languages, Noah had built an ark to save two of every animal, and Adam and Eve were the first humans.12

and Clarence Darrow | Smithsonian Institution

The State’s Attorney tried to stop Darrow’s intense cross-examination several times. Bryan refused to allow it. He was not scared to stand up for his religion. Bryan hesitated though when it came to answering if God had actually created the world in seven days. He confessed that the seven days were perhaps actually seven epochs. He was not familiar nor interested in science that contradicted Biblical teachings, he admitted. The crowd laughed at Bryan as he began to falter. Bryan’s followers expressed disappointment at the weakness of his answers. The judge finally halted the questioning himself but it was too late. Darrow’s plan to humiliate Bryan had worked.13

All the contents of the cross-examination were struck from the record. They were considered irrelevant to the actual purpose of the trial. The judge sought to answer a simple question: was Scopes guilty or not of teaching evolution to his class? Darrow didn’t hesitate in answering the judge’s question. He requested that the jury be brought back so they could declare Scopes guilty.14 Darrow then waived the defense’s right to make a closing statement. It was a spiteful move. By forfeiting his right, Darrow had also forfeited the prosecution’s right to make their own closing statement. He wanted to deny Bryan his final opportunity to preach his religious and anti-evolutionism ideals before the court. The jury declared Scopes guilty after only nine minutes of deliberation. Judge Raulston ordered Scopes to pay a fine of $100.15

The trial ended after eight days. Five days after the case closed, a heart attack took Bryan in his sleep. Shortly before he died, Bryan’s doctor had warned him to take it easy. He was concerned about the combination of Bryan’s poor heart and diabetes. Instead, Bryan had spent his last few days busy. He traveled in and around Dayton, examining land for where a new school could be built and giving sermons to crowds in the searing heat. In his free time, he worked on editing the anti-evolution speech Darrow had denied him the chance to give. It would have been 15,000 words long if published.16

Scopes’ case stood before another court a year later. This time it was the Tennessee Supreme Court presiding. Darrow and the ACLU intended to escalate the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the plan fell through. Scope’s conviction was overturned due to a small technicality: the law called for the jury to set the fine, not the judge. After his case had been settled a second time, Scopes returned to a quiet life. He left Dayton to study geology at the University of Chicago. He traveled to Venezuela to work for an oil company before returning to America and moving to Louisiana. He died there in 1970. Rappleyea also moved away after the trial. Always business-minded, Rappleyea experimented with new investments in Cuba and Canada. Darrow lived another thirteen years after the trial. He returned once to Dayton. “I guess I didn’t do much good here after all,” he remarked when he saw the new church Dayton had built.17

The Butler Act wouldn’t be repealed until 1967. Even after, the battle for teaching evolutionism in the class was still not over. Attempts at passing legislation to restrict evolutionism and push creationism would continue. A bill proposed by the Tennessee General Assembly in 1997 required that both sides must be taught equally as theories. Another Tennessee bill proposed in 1996 tried completely banning evolutionism in the class once again.18 Though Scopes had technically been found guilty, his trial was considered a success in other ways. It had succeeded in putting Dayton on the map. It also brought national attention to the discussion of evolution and the extent of religion’s legal power. What had started as a business venture turned into a story of an underdog defending his right to academic freedom and free speech.19

- R. M. Cornelius, “Their Stage Drew All the World: A New Look at the Scopes Evolution Trial,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1981): 131. ↵

- Adam Frank, “The Conflict We Know: Religion, Science, and the Modern World,” in The Constant Fire, 1st ed., Beyond the Science vs. Religion Debate (University of California Press, 2009), 38. ↵

- Joan Delfatorre, “Here Comes Darwin,” in Knowledge in the Making, Academic Freedom and Free Speech in America’s Schools and Universities (Yale University Press, 2010), 126. ↵

- Edward J. Larson, “The Scopes Trial and the Evolving Concept of Freedom,” Virginia Law Review 85, no. 3 (1999): 512-513. ↵

- R. M. Cornelius, “Their Stage Drew All the World: A New Look at the Scopes Evolution Trial,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1981): 130-134. ↵

- Judith V. Grabiner and Peter D. Miller, “Effects of the Scopes Trial,” Science 185, no. 4154 (1974): 832. ↵

- R. M. Cornelius, “Their Stage Drew All the World: A New Look at the Scopes Evolution Trial,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1981): 131. ↵

- Walter Prichard Eaton, “Clarence Darrow: Crusader for Social Justice,” Current History (1916-1940) 35, no. 6 (1932): 786–787.“ ↵

- Ferenc M. Szasz, “The Scopes Trial in Perspective,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 30, no. 3 (1971): 297. ↵

- William E. Ellis and Charles Reagan Wilson, “Scopes Trial,” in The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. JAMES W. ELY and BRADLEY G. BOND, Volume 10: Law and Politics (University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 123. ↵

- Randy Moore, “Creationism in the United States: I. Banning Evolution from the Classroom,” The American Biology Teacher 60, no. 7 (1998): 493-494. ↵

- Fay-Cooper Cole, “A Witness at the Scopes Trial,” Scientific American 200, no. 1 (1959): 128. ↵

- Fay-Cooper Cole, “A Witness at the Scopes Trial,” Scientific American 200, no. 1 (1959): 128. ↵

- Fay-Cooper Cole, “A Witness at the Scopes Trial,” Scientific American 200, no. 1 (1959): 128. ↵

- Marjorie Garber, “Cinema Scopes: Evolution, Media, and the Law,” in Law in the Domains of Culture, ed. Austin Sarat and Thomas R. Kearns (University of Michigan Press, 1998), 125. ↵

- R. M. Cornelius, “Their Stage Drew All the World: A New Look at the Scopes Evolution Trial,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1981): 137. ↵

- R. M. Cornelius, “Their Stage Drew All the World: A New Look at the Scopes Evolution Trial,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1981): 137-138. ↵

- Edward Caudill, “The Contrarian and the Commoner: Darrow and Bryan,” in Intelligently Designed, How Creationists Built the Campaign against Evolution (University of Illinois Press, 2013), 43. ↵

- Edward J. Larson, “The Scopes Trial and the Evolving Concept of Freedom,” Virginia Law Review 85, no. 3 (1999): 521. ↵

5 comments

Helena Griffith

It’s particularly intriguing that the freedom of expression amendment led to the initial passage of such a repressive statute. I’m curious as to why more individuals didn’t realize that it was a violation. The explanation of the two quarreling attorneys in the article truly helped me comprehend why the case was receiving so much attention. It puzzled me that this entire case was truly intended to boost the image of tiny towns with struggling economies.

Courtney Mcclellan

Its really interesting that such a restrictive law was passed in the first place because of the freedom of speech amendment. I wonder why people couldn’t see that it was really a violation. The article was really interesting and the explanation of the two feuding lawyers really helped me understand why there was so much attention involved with the case. I found it odd that this whole case was really a publicity thing for small towns with poor economies.

Dylan Vargas

The article talks about a time that was very controversial in which a law was passed where you couldn’t talk about evolution in school. Then in Dayton, Tennessee a business man named George Rappleyea decide to make something of the situation and got John Scopes to go into trail about evolution in class. Where the trail went on and got a lot of coverage from the media. The article gives us the background and the major events and people which is a good way to tell what events had happened during this time. Also bringing a story of a major event that happened at the time.

Javier Oblitas

The article was very well written and knew how to grab the readers attention. I hadn’t known about the battle for evolution in the classroom, nor that this trial was all staged by the people to bring attention to their small town. I personally would not have had the patience John. T. Scopes had during the trial let alone being prosecuted for something he had not done. I thought the public setup was funny as well as calling it the “monkey trial.”

Kimberly Rivera

This article was extremely interesting and it drew in the reader. From the very beginning to the end the story of the Scopes Monkey Trial and how it started from a ruse to draw attention to Dayton to help the economy, to the trial case where the lawyers weren’t necessarily focused on defending or fighting the case but in earning revange and humiliation. This story was one that i loved learning for the first time.