Winner of the Fall 2017 StMU History Media Award for

Best Article in the Category of “Crime”

Think back to the first horror movie you ever watched. Was it Halloween? Nightmare on Elm Street? Friday the 13th? Think about what all these movies have in common. If you guessed death, then you’re right. Most people will say they love a good horror film because of the rush of adrenaline; others will say they love the absurdity. Regardless of the reason, there is still a love for all things horror.

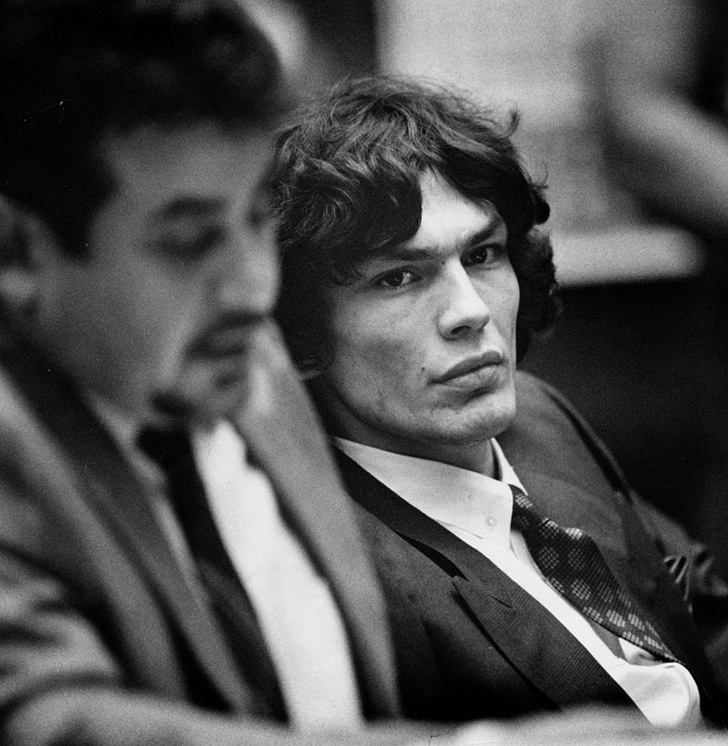

But, where does this culture come from? While there are some people that love fictional horror, there are those that love real-life horror. These men and women idolize and fantasize about serial killers and murderers. They study all the crime reports, watch every documentary, and read every biography or narration of a killer’s life. Why is it that men and women like Richard Ramirez, self proclaimed satanist and vicious murderer, become celebrities through their killing? Serial killers sometimes gain groupies and copy-cat killers. Ramirez is one of many examples of distorted stardom but, his story gives us an image of America’s culture of death and our obsession with serial killers.

There are countless examples of killers being studied and filmed for the purpose of entertainment. Serial killers like Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer have had numerous documentaries appear, studying and depicting their lives. Books like The Stranger Beside Me and Zodiac have made millions in simple narration of the investigations or the killings themselves. Even Ramirez has had his name in Hollywood several times. He was depicted in one episode of the 2015 season of American Horror Story, and in 2016, Lou Diamond Phillips portrayed Ramirez in a dramatization of his life in A&E’s The Night Stalker.1 A Google search of his name will turn up thousands of articles and blogs detailing his life and killings. On YouTube, there are hundreds of videos from Ramirez’s trial along with subsequent interviews. Scrolling through the comment section, there are varying opinions on Ramirez. Some call him charming and philosophical, others say he is cocky and Charles Mansonesque.

Then, you will find men and women who find Ramirez attractive. This psychological phenomenon is known as hybristophilia, a type of paraphilia where a person is sexually attracted to and aroused by a person who has committed a vicious or gruesome crime.2 While Ramirez was still alive and in prison, hundreds of women would line up to try and visit him. At one point there were so many women in line, that more than half had to be turned away. Ramirez himself ended up marrying one of his “fans” while in prison. This woman was Doreen Lioy, a forty-one year old freelance editor. They were married on October 3, 1996 and remained husband and wife for twelve years before Ramirez died of B-cell lymphoma at the age of fifty-three.3

While she was the only woman to have married Ramirez, she was not the only woman “in love” with him. From the time of his arrest to his death, there were hundreds of “women in black” who wrote him letters in jail and went to every court hearing of his. Below is a news segment featuring two of Ramirez’s deluded fans.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Rlm-n3vfVM

To the average person, a serial killer is not a person, but a monster incapable of giving or receiving love. Very few would look into the eyes of a murderer and feel overcome with affection. But, in the 1980s and 1990s when Ramirez’s trial was all over the news, Americans couldn’t get enough of him. And so, the rise of serial killer notoriety comes to a peak, with an all-time high of serial killer reporting taking place and law enforcement spending more time and funding trying to understand serial killer psychology and motivation. Thus the culture of death was born.4

That is not to say that serial killers or murderers have not existed in history previously. They have, but there was not nearly as much attention given to them. The mid-twentieth century saw a worldwide increase in serial killers and mass murderers. This phenomenon has been documented all the way through the twentieth century, with a high concentration of killers and murders in the United States. Interestingly enough, there has been no evidence to show a slowing point to this killer influx. The rate of murder and killing has exponentially grown through the twentieth- and into twenty-first century. Because of this, there is an increase of study and focus being put onto these killers and atrocities. Many scholars and public health practitioners have devoted their time to researching and interviewing these killers in hope of understanding their motives for committing such heinous crimes.5

Though, with all this research, the primary focus is always put on the killer and their survivors, if any are left. In situations of a serial killer being found and arrested, public health officials will spend time talking about the crimes committed and their political and social ramifications. And, while they investigate and interview those who knew the killer, sometimes a motive is never found, leaving the community to deal with the loss of life in a shroud of mystery and anguish.6

So, with all the time and resources devoted to understanding and predicting psychotic behavior, there has been no major breakthrough. Most of this difficulty comes from how “normal” these killers and murderers look. They could be friends, co-workers, or even family members—they blend in.7 Take for example The Stranger Beside Me, written by Anne Rule. She wrote about her experiences with Ted Bundy and described how she was completely shocked by the atrocious crimes he committed. But, before his arrest, he was a master of disguise and incredibly charming; there’s no way a man like that could be a cold-blooded killer. Right?

When speaking about Richard Ramirez, there was no surprise that he was troubled. As a child, he was diagnosed with epilepsy and grew up under the influence of his older cousin Mike. His older cousin was a Vietnam veteran who taught Ramirez to kill and smoke weed. As Ramirez grew older he began stealing to pay for a growing drug addiction; during this time, he also began to see himself as a child of Satan. As he grew, he became more troubled, working at a hotel and then being fired for trying to rape a woman in her room. He was sixteen at that time, though Ramirez was not found guilty because the Judge felt he had been lured into sex rather than the one to force it.8

After dropping out of high school, Ramirez, at the age of eighteen, moved to California and became a full time criminal. As his addiction to drugs grew, so did the violence of his crimes, resulting in a deadly cocktail of rage and addiction. All of this came to a climax in June of 1984, and after brutally murdering his first victim, seventy-nine year old Jennie Vincow, he went on a year-long killing spree.9 The wake of destruction he left after every break-in and murder left the nation in shock and terror. After every rape and murder he committed, a pentagram could be found either on the body of his victim, or somewhere in the crime scene, and this became Ramirez’s signature.10

He was finally apprehended on August 31, 1985 after his last victim was able to look out the window, and see the stolen car he was driving and a portion of the license plate. When Ramirez was found, he was in an East L.A. neighborhood, and police officers had to stop residents from beating him to death.11 But, during his trial there was no clear motive found. The disturbing conclusion was that Ramirez killed people and raped women because he liked it. And so, there comes a battle between sympathizing with Ramirez because of his traumatic and turbulent childhood, and condemning him as a “Satan-obsessed serial killer who enjoyed every murder and rape he committed.”12

The media had a large influence on this tug of war. From the first murder he committed to his very last day in court there was no shortage of stories. The more stories printed about “The Night Stalker,” the more the public wanted. News outlets focused on his surviving victims and the gruesome details of his crimes. News had begun to focus on the spectacle of things. Newspapers depicted his crimes as atrocities and disasters to the L.A. and San Francisco area, and every story of his made the front page. As Mary Ann Doane, a commentator on mass media, said “Catastrophe is at some level always about the body, about the encounter with death.”13

So, as a society we became obsessed with death. Even now, thirty-two years after Ramirez’s arrest and four years after his death, we still watch his documentaries, we still read the biographies, we still find him disturbingly fascinating. Richard Ramirez still has our attention.

- “Richard Ramirez Biography,” biography.com, last modified October 13, 2017, https://www.biography.com/people/richard-ramirez-12385163. ↵

- James Alan Fox, “Lovesick over Charles Manson. Really?,” USA Today, (2014): 08a, 6 October 2017. ↵

- “Richard Ramirez Biography,” biography.com, last modified October 13, 2017, https://www.biography.com/people/richard-ramirez-12385163. ↵

- Judith S. Baughman, Victor Bondi, Richard Layman, Tandy McConnell, Vincent Tompkins, eds., “Serial Killers and Mass Murderers,” in American Decades Vol. 9, 1980-1989, (Detroit: Gale, 2001). ↵

- D. L. Peck and R. B. Jenkot, “Serial and Mass Murderers,” in International Encyclopedia of Public Health Vol. 5, 690-691 (Oxford: Academic Press, 2008). ↵

- D. L. Peck and R. B. Jenkot, “Serial and Mass Murderers,” in International Encyclopedia of Public Health Vol. 5, 690-691 (Oxford: Academic Press, 2008). ↵

- Jarlath Killeen, “The Monster Club: Monstrosity, Catholicism and Revising the (1641) Rising,” in The Emergence of Irish Gothic Fiction: History, Origins, Theories 2014, ( Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 5. ↵

- J. Gordon Melton, “Ramirez, Richard (1960-),” in Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, (Detroit: Gale, 2001), 1279. ↵

- “Richard Ramirez Biography,” biography.com, last modified October 13, 2017, https://www.biography.com/people/richard-ramirez-12385163. ↵

- J. Gordon Melton, “Ramirez, Richard (1960-),” in Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, (Detroit: Gale, 2001), 1279. ↵

- “Richard Ramirez Biography,” biography.com, last modified October 13, 2017, https://www.biography.com/people/richard-ramirez-12385163. ↵

- Jarlath Killeen, “The Monster Club: Monstrosity, Catholicism and Revising the (1641) Rising,” in The Emergence of Irish Gothic Fiction: History, Origins, Theories 2014 ( Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 5. ↵

- Mark Seltzer, “Serial Killers (11): The Pathological Public Sphere,” Critical Inquiry 22, no. 1 (1995): 131. ↵

109 comments

Ryann Cervantes

Wow what a good, well thought out article. I like how you included “hybristophilia” and gave a reason for this romanticism on murderers. I had heard about The Night Stalker and I know that he had a fan base that idolized him but never knew why. I just thought everyone was crazy. This is also one of the reasons why criminals should never be treated as a celebrity during trials, because of the danger that attention can attract or support.

Megan Barnett

It is crazy to learn that so many women were lined up to see Ramirez and that there is even a word for someone who is attracted to someone else who has committed a gruesome crime. Your article was well written however I think you could have been more focused on your topic because the first few paragraphs dragged on.

Zeresh Haman

This is a fascinating article. It is very true that many people are attracted to murder, it is part of our culture. The fact the Ramirez married one of his fans is really crazy and the fact that there were so many women that were in love with him and went to visit him in prison is just one of the examples of how serial killers have been romanticized. This was a great article, and was very well written.

Mario Sosa

This was a really intriguing article, as I have never heard about hybristophilia before. I do not understand how a serial killer could have so many fans and admirers. I will admit though that serial killers are a very fascinating subject. I find it interesting that serial killers like Richard Ramirez and Ted Bundy are able to blend into society and behave normally in public despite their cruel nature and lack of affection. Nicely done article, fantastic job!

Grace Bell

I love reading articles that talk about anything that has to do with murderers or murder, it is such an interesting topic to talk and learn about. It is always interesting reading about past murderers that have become well known for what they did and how people reacted to their gruesome crimes. There has to be something seriously wrong with those people though because a normal person shouldn’t be able to commit the crimes they commit. This was a great article, great job!

Benjamin Voy

What a very interesting but disturbing story. Its so strange that someone could;d have such an obsession with such a weird and dangerous hero. Ive heard of sportiness and pioneers but never a mass murdering hero. Its also strange how much of a hit he was with females as well. He really must have lived the double life. A great article using great language

Crystalrose Quintero

The article began with such a strong opening by indicating that people romanticize and idolize real murders and serial killers. I had no idea that there was a psychological condition for those that are attracted to someone who has committed a vicious crime. This article described the vicious Richard Ramirez with such detail that it was easy to portray what kind of a man he was and what led up to his becoming of such a dark person.

Erin Vento

I’m really glad you mentioned that American Horror Story had his character in there because that helped me remember that I had heard of him before. You’re right though; America loves hearing about horrible things like that after they’ve happened and a lot of people get some sort of excitement from it. The letter and video you included in the article was really cool and gave us a little more insight on how oddly and wrongly in love people were with him.

Rebekah Esquivel

This article caught my attention with the title. It seemed interesting and made me want to read your article. I agree that society has this kind of fascination with crime and serial killers as it did back in those days as well. Now we have tv shows and movies made based on certain serial killers in history. I myself find some of these shows pretty interesting but I wouldn’t go as far as to say that I am obsessed in any way. It is so shocking how Ramirez had women lined up to see him while he was in prison and were infatuated with him. The fact that he married one of his fans is also shocking to me. That must have been a very interesting kind of relationship as i’m sure the visits from other women didn’t stop once he was married. Very informative and interesting article to read.

Alexandria Martinez

You are completely right in saying that the world fantasizes over murderers, society loves to hear about all of the horrible things someone has done and why they did it in the first place. Yes, we may not like the fact that lots of murders and crimes were committed but we still love to watch documentaries and read articles about people who committed such crimes. Society even gives it so much attention that sometimes people will commit such crimes so that they can just become famous.