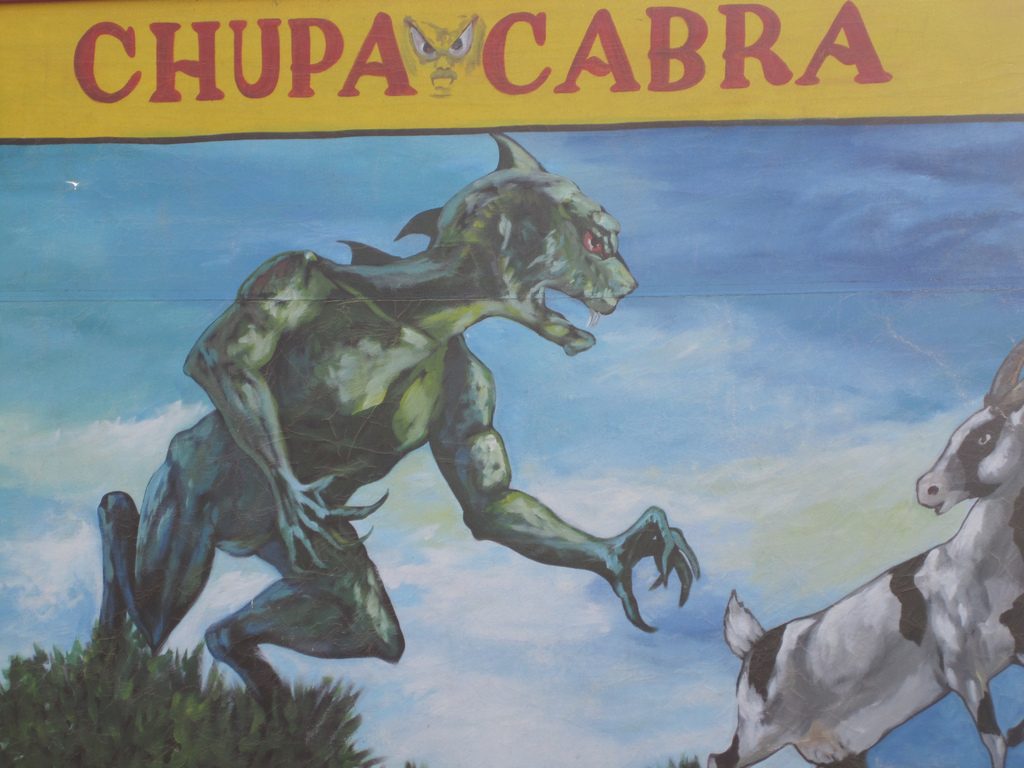

Although the earliest reported sightings of the chupacabra were in the 1990s, the legendary creature has become deeply seated in the public consciousness. Those who believe that the chupacabra exists insist on its reality in spite of there being no photographical or scientific evidence of the species.1 Nonetheless, “flesh and blood chupacabras have supposedly been found as recently as June of 2017, making the monsters eminently more accessible for study than, say, the Loch Ness monster or Bigfoot.”2 The term chupacabra literally means goat sucker, referring to reports of this creature killing goats and drinking their blood. Therefore, the chupacabra has a symbolic link to the vampire. As interesting as the chupacabra might be, the sociological and psychological effects of these reports are equally fascinating. Since 1995, more than two hundred reports of chupacabra have surfaced, all from North America and most from Puerto Rico.3 These reports have led to negative effects in the affected communities, including widespread panic and unnecessary killing of wildlife.

The chupacabra has been spotted mainly in the United States and Mexico, and especially in Puerto Rico where the legend was originally born. As journalist David Moye points out, several residents of a small town in Texas have not just reported seeing the chupacabra, but also claim to have preserved chupacabra corpses.4 The scientific explanation most typically given for the chupacabra is not that it does not exist at all, but rather that it is simply a wild animal mistaken for the mythical creature. The most common explanation is that the chupacabra is a coyote with mange, which often appears “quite debilitated,” and which may prey on easy targets like livestock.5 Moye also states that some believe the chupacabra to be a type of raccoon. DNA analysis on a suspected corpse has revealed that in at least one case, the suspected chupacabra was nothing more than a “hybrid of a coyote on the maternal side and a Mexican wolf on the paternal side.”6 Nevertheless, not all sightings of the chupacabra are canine in appearance. Almost all the earliest sightings until 2000 were decidedly un-canine and described as “a bipedal creature that was three feet tall and covered in short gray hair, with spikes out of its back.”7

Although the chupacabra stories started to surface in the 1990s in Puerto Rico, Benjamin Radford, author of a book on the chupacabra, points out that there were earlier sightings throughout the twentieth century.8 The stories and the folklore surrounding the chupacabra have dramatically changed over the years, perhaps accounting in part for the shift in its appearance from an odd bipedal creature with spikes to one more canine in appearance and behavior.9 Bale describes the extent of the original reports of the chupacabra, noting that in 1994, residents of Canóvanas, Puerto Rico, had reported dozens of wildlife fatalities not limited to goats. Following the Puerto Rican reports, over two-thousand more farm animals were reported dead via a “grotesque creature about three feet tall, with membraned wings, a hunched back, large eyes, covered with either scales or quills.”10 Some reports also offer the chupacabra the additional sinister feature of “glowing red eyes.”11 Given its fearsome appearance and the trail of destruction left in its wake, it was no wonder that the affected communities started to panic. Whenever and wherever chupacabras had been spotted, residents of the community would go so far as to completely board up their residences, take up arms, and hire guards to protect their loved ones.12 In fact, some ranchers even started to sell off their herds to minimize their financial losses in anticipation of both drought and further chupacabra attacks. In California, a wave of chupacabra sightings led livestock owners and ranchers to declare “open season” on protected wildlife like mountain lions, leading to mandatory police controls of affected areas.13

The panic surrounding chupacabras became so widespread and potentially devastating to local communities that the governments of Mexico, Puerto Rico, and even the United States were forced to step in. As Bale points out, international press conferences ensued, including reports from “prominent biologists” who offered their theories about what the chupacabra could have been, plus another autopsy of a corpse conducted in Miami, which yielded results of the creature to be either a “puma or a dog.”14 Likewise, in 2007, biologists in Texas analyzed the DNA of a chupacabra and found it to be nothing more than a coyote.11 The biologists’ conclusions did little to assuage fears, as the analyses seemed inconclusive, lacking concrete and definitive evidence about what the creature might have really been and why so many continued to see something bipedal and vampiric. Even when the stories started to change, morphing the chupacabra into a canine creature, ranchers and farmers continued to cling to their claims and spread rumors.

The “confusion and contradiction” surrounding chupacabras comes from both sides of the debate, with reported sightings being too diverse and lacking in cohesive description to be seriously credible, and yet with scientific explanations also lacking substance.16 Given the diversity of reports, both in terms of their geographic locations, the description of the creature itself, and its effect on wildlife, it has been as difficult to debunk the existence of the chupacabra as to prove its existence. Unlike Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster, there have actually been specimens that have been examined and tested, as well as thousands of animal victims of the chupacabra. Therefore, the legend of the chupacabra continues to proliferate and sink quickly into popular culture. Panic is less likely to be the reaction to a chupacabra reporting now, being replaced by a sense of pride in local customs and a mistrust of the government. In essence, the chupacabra plays perfectly to the tune of global conspiracy theorists.

The chupacabra is now known globally, even though its terrain remains geographically restricted, just as with the Loch Ness monster or any similar creature like the yeti. Mainstream news networks, from NBC and CNN to Univision and BBC, have all picked up on chupacabra stories, albeit reporting those stories in a clearly skeptical way.17 The television shows X Files and Scooby Doo both dedicated episodes to chupacabras, who also appeared on countless t-shirts and of course, Halloween costumes.18 A good number of these popular culture references are, of course, tongue-in-cheek, which has revealed an ancillary phenomenon: what Bale calls “a popular commentary on modernity,” similar to the Frankenstein legend.19

There is another important sociological and political effect from the chupacabras: the divide between the guardians of secularism and modernity versus those who believe in the importance of tradition and religion. Whereas it is easy for progressive, secular societies to dismiss the chupacabras out of hand, those who honor the legend, even for humorous purposes, acknowledge that folklore and storytelling play a significant role in human society. Folklore can link people together, offering the means by which to escape the harsher realities of war and climate change. There is also the fact that the people who have reported chupacabra sightings genuinely believe in the creature, and that it threatens their livestock and ways of life. When people from urban areas or communities in far away places start to wear a chupacabra t-shirt, it seems insulting to those who actually do believe that it exists and is a serious public safety concern. In fact, the people of Canóvanas, Puerto Rico, and small rural ranching communities in Mexico felt denigrated and “manipulated” by the mainstream media who painted them as “ignorant hicks,” and Bale also claims that the legend represents the means by which urban legends are used to expose or mirror angst in the public consciousness.20 Thus, chupacabras are at least an opportunity to study the symbolism and function of cryptozoology, as well as a means of studying the ways people manufacture supernatural stories for political or sociological purposes.

Interestingly, the chupacabra is never depicted as a creature that harms humans; it only targets livestock. This differentiates the chupacabras from vampires. Yet given that the chupacabra does inflict harm on human communities, it is a sinister symbol of terrorism and oppression. The stories occasionally run dry for several years, only to resurface with a vengeance when a farmer loses hundreds of goats or cattle at once and blames chupacabras. As Robert Jordan points out, too, the elusive platypus was once believed to be a fake creature relegated to cryptozoology as late as the eighteenth century.21 Therefore, the chupacabra may indeed exist. The question would then be: what does the chupacabra actually look like, if half the reports describe one thing and the other half something totally different?

Whether or not the chupacabra exists, the legends and stories are compelling in their own right. The stories are unique to North America, just as the Loch Ness monster is unique to Scotland. Furthermore, the descriptions of the chupacabra have changed significantly, showing how legends and stories can morph while still preserving their core essence and meaning. Finally, the chupacabra represents at once the reactions of rural people who are frequently painted as being backwards, as well as the condescending reactions of urban people who believe themselves to be superior, nonplussed by superstition or legend.

- Benjamin Radford, Tracking the chupacabra: the vampire beast in fact, fiction, and folklore (UNM Press, 2011), 133. ↵

- Robert Michael Jordan, “El Chupacabra: Icon of Resistance to US Imperialism,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at Dallas, 2008), 4. ↵

- Robert Michael Jordan, “El Chupacabra: Icon of Resistance to US Imperialism,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at Dallas, 2008), 7. ↵

- Moye David, “Living Chupacabra Captured By Texas Couple?” Huffington Post: Weird News, (April, 2014). ↵

- Robert Michael Jordan, “El Chupacabra: Icon of Resistance to US Imperialism,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at Dallas, 2008), 5. ↵

- Moye David, “Living Chupacabra Captured By Texas Couple?” Huffington Post: Weird News, (April, 2014). ↵

- Robert Michael Jordan, “El Chupacabra: Icon of Resistance to US Imperialism,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at Dallas, 2008), 4. ↵

- Benjamin Radford, Tracking the Chupacabra: The Vampire Beast in Fact, Fiction, and Folklore (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 43-44. ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41, Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 51. ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41, Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 48. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “Chupacabra.” ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41, Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 54. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “Chupacabra.” ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41 Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 57-58; J. Gabbatiss, “The truth about a strange blood-sucking monster,” BBC Earth (10 Nov, 2016). ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “Chupacabra.” ↵

- Benjamin Radford, Tracking the Chupacabras (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 69. ↵

- J. Gabbatiss, “The truth about a strange blood-sucking monster,” BBC Earth, (10 Nov, 2016). ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41, Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 57. ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41, Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 60. ↵

- Jeffrey M. Bale, “Political paranoia v. political realism: on distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics,” Patterns of Prejudice (Taylor & Francis Online), Volume 41, Issue 1 (February 1, 2007): 60, 292. ↵

- Robert Michael Jordan, “El Chupacabra: Icon of Resistance to US Imperialism,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at Dallas, 2008), 3. ↵

64 comments

Valeria Hernandez

The article is interesting as Andrea Chavez explains the history of a famous myth about a vicious beast that resembles a vampire. However, I believe the article is too long. However, the author has a lot of validity towards her argument. She is able to smoothly transition into a descriptive story arc that gives authors an idea of what the actual story to the Myth of the infamous beast “chupacabra.”

Justin Garcia

This is a very interesting article. The stories about the Chupacabra have been around for a long time. To see how the story changed over the years is fascinating. The fact that a story with no real evidence could affect peoples way of life is shocking. Residents in areas that have been said to be locations of Chupacabras leave many fearing for their livestock and themselves. Overall a great article.

Cameron Ramirez

I can distinctly remember reading about all the many supernatural and legendary creatures in a book back in elementary school. My friends would always talk about how there parents saw or had friends that saw the mysterious chupacabra. As a young kid I was mortified at the thought of a three foot tall blood sucking creature that would suck the insides out of small animals. I knew that of course the elusive chupacabra didn’t exist but you can never be to sure as a young kid. Anyways, great article on the history and folk lore of the chupacabra. Your post was written well and was a good read. Keep up the good work.

Mark Martinez

A well written and put together article. Everyone has heard the legend of the Chupacabra but the amount of detail put into this article is amazing. You would think that the legend would only be a story and not have such a massive history. For people to get afraid or offended just from someone wearing a Chupacabra t-shirt shows how well routed this story has become.