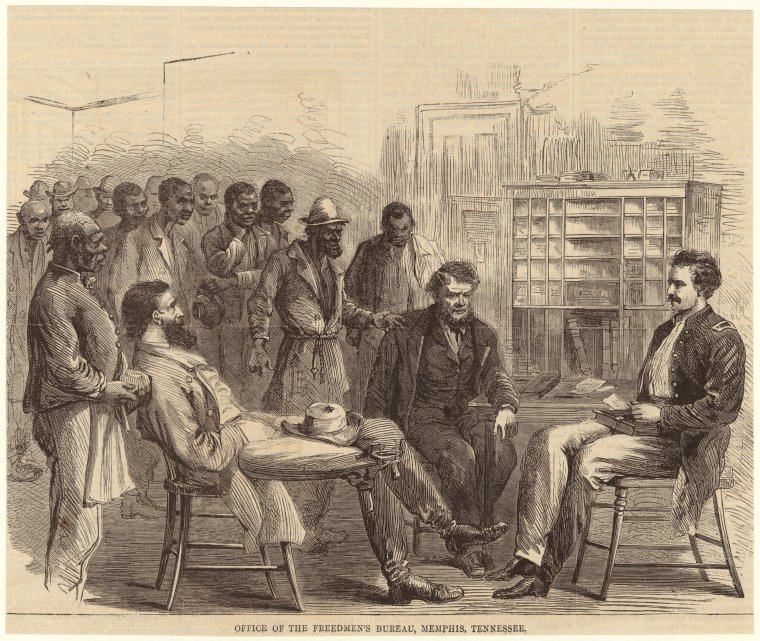

In March of 1865, just before the ending of the Civil War, the Federal government created the Freedmen’s Bureau.1 Initially set up to help the roughly four million freed slaves, it also had provisions for helping poor white Southerners who were similarly destitute after the Civil War. In fact, the Freedmen’s Bureau was designed to help those in need throughout the South.

The Bureau had provided needed necessities that included clothing, food, shelter, and education. It also helped many freedmen gain land ownership. Congress had several reasons for creating this act, but the main purposes were to maintain abandoned lands in the South and to provide education for the freed slaves.2 Most freedmen wanted to obtain an education so they could make a start with their newly found freedom. It is fairly difficult to start a successful life without an education; therefore the bureau helped them out in many ways.

The educational goals of the Freedmen’s Bureau were only partially met. By 1870, the Bureau managed to educate 200,000 students with a teaching staff of 9,000 in only 4,000 schools.3 By the time the Freedmen’s Bureau ended in 1876, more than half of white children and about 40 percent of colored students were attending school.3 One of the main contributors to the Freedmen’s Bureau was the American Missionary Association, which was an organization founded in September 1846.5 The Association wanted to abolish slavery and give African Americans an education. They supported equal rights for all races and they promoted Christian values. Between 1867 to 1870 the Freedmen’s Bureau allotted $243,753.22 from the Association for working with the freedmen and refugees. 6

However, obtaining an education was more difficult than expected, even with the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Although the Bureau supplied the accommodations needed for the education program, the white Southerns had other plans for the schools. Most white Southerners were resistant to the idea of letting African Americans obtain an education. They believed that the newly freed slaves would get a false hope of equality, or would aspire to live as equals with whites. They feared that with their new freedom and education, the freedmen would be less willing to work for their former owners. They believed that providing freedmen with an education was a waste of money, because they believed that blacks were unfit by nature to profit by formal education. Others argued that any education of the freedmen would lessened his or her usefulness as a laborer.7 However, whatever the arguments were about the education program, the work of the Bureau proceeded.

Eventually, the white Southerns, fearing that the freed slaves would get an education, started taking matters in there own hands. They began taking control of the administration for education in the South. The provisions of the Freedmen’s Bureau made integrated schools possible, but virtually all whites opposed this idea. The first integrated school during the Reconstruction era was in New Orleans; however, whites refused to attend.8

Since the schools were being segregated, colored from non-colored people, the idea of having integrated schools in the South would have to wait another eighty years.

The Freedmen’s Bureau had its challenges. Overall, the Freedmen’s Bureau took steps forward for educating former slaves in the midst of hostile and chaotic times, the period we call Reconstruction.

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past Volume 2, 15 edition (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014), 409. ↵

- Marjorie H. Parker, “Some Educational Activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Journal of Negro Education 23, no. 1 (1954): 9. ↵

- Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past Volume 2, 409. ↵

- Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past Volume 2, 409. ↵

- Richard B. Drake,”Freedmen’s Aid Societies and Sectional Compromise,” The Journal of Southern History 29, no. 2 (1963): 176. ↵

- Marjorie H. Parker, “Some Educational Activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Journal of Negro Education 23, no. 1 (1954): 12. ↵

- Marjorie H. Parker, “Some Educational Activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Journal of Negro Education 23, no. 1 (1954), 10. ↵

- Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past Volume, 409. ↵

27 comments

Mariana Sandoval

It’s great that not only did the Freedmen’s Bureau aim to meet the basic needs of freedmen through things like clothing and food, but they also aimed to help them thrive in their new lives through the form of education. Education is so important! While this is great, unfortunately it is clear to see that many white Southerners were threatened by blacks receiving an education because education is so empowering. The Freedmen’s Bureau had such a liberal standpoint considering the time period is was formed in and sadly the South was not ready to adopt these ideas. We can see the effects that their rejection of these ideas had on Southern society even in the 20th century- segregated schools; superior attitude towards blacks even though they were free now; etc. It’s disheartening to see that so many people were stuck in their old ways and had to continue to be discriminatory.

Jezel Luna

I did have prior knowledge about the Freedmen’s Bureau. However, I was not aware that they managed to educate 200,000 students. I admire the strive they had for former slaves especially when others would refuse to attend the integrated schools. Education is so important and shouldn’t be limited to anyone. Great topic!

Rachel White

I was aware of the basics of the Freedmen’s Bureau, but I had no idea that they were teaching 200,000 students with a staff of only 9,000! That is a very high student-to-teacher ratio! It is amazing that even back then, the power of education was not only powerful, but feared in the hands of African Americans. It is amazing to think how far our school system has come since then in regards to standards and material. This was a very interesting topic and I enjoyed learning more about the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Celina Resendez

Great job Amanda! I know as a future educator, this topic really spoke to you; it does to me as well. Education has come such a long way, but it seems we are still facing a lot of prejudices in the school system. Many may not want to talk about it or admit that it is there, but it’s true. Teaching is my passion and I hope to make a difference in the lives of the children I get to spend time with. I hope, when that door shuts to my classroom, that we can throw everything about prejudice out the window and work together, collaboratively as a class to encourage, inspire, and learn from one another.

Edelia Corona

I learned a lot from reading your article! It was well written and engaging. One thing I learned was what the Freedman’s Bureau was. I never even heard of it so it amazes me that there were actually schools for African Americans and whites at this time. It is sad it did not thrive in the South and that it would have to wait another 80 years for integration.

Soki Salazar

This article was very well written! This was a topic I did not know anything about and through this article I learned about the Freedman’s Bureau. It was surprising to find out how many students they educated with the amount of staff and schools they provided and it was interesting that only 40% of African Americans were being educated under the circumstances.

Priscilla Reyes

Loved the conclusion. Though the Freedman’s Bureau came to an end in the hands of white southerners, it was the start of African American education and should be greatly remembered.