On January 9, 1884, three days after Gregor Mendel’s death, a huge cloud of smoke could be seen rising from the Abbey of St. Thomas. This abbey is located in the Moravian city of Brno, currently in the Czech Republic, and during the 1800’s, it was the cultural and administrative center of the region. Earlier that January morning, Gregor Mendel, the man who is now considered the father of genetics, had been laid to rest. After this ceremony, the friars of the monastery proceeded to ignite a fire on the hill behind the convent. In an attempt to purge the monastery of Mendel’s influence, they burned all of his personal papers, notes, and recordings from his years of experiments. What prompted this extreme demonstration? Were the brother’s actions uncalled for? How is it that they overlooked the importance of these papers, in light of the stature that Mendel’s work in genetics holds today?1

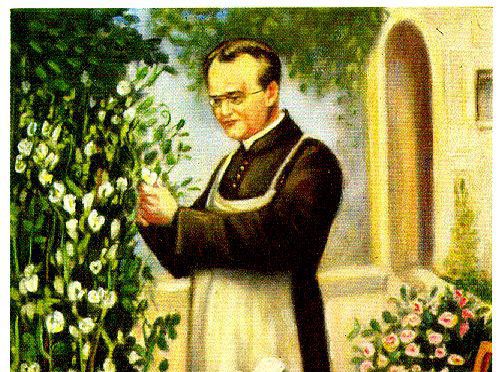

From a humble family, Johann Gregor Mendel was born in 1822 in Heinzendorf bei Odrau, a small town located in present-day Czech Republic. Growing up, he attended the village school where he was taught natural science. Both of his parents were gardeners, so in his free time, Mendel worked in the family orchard. Together, his background in natural science and his experience in horticulture, which is the practice of garden cultivation, would prove crucial later on in Mendel’s career and his experiments.2

After completing primary and secondary school, the local school master recognized Mendel’s above average intelligence, and he pushed Mendel to continue his education. Consequently, Mendel was sent to a Gymnasium for learning, which is similar to a modern-day high school. Here, Mendel continued to pursue his education. However, he would get easily stressed, and he had bouts of clinical depression. The stress and occasional depression often made him sick, and this proved to be a major roadblock to his education. At one point in time, he did not attend school for four months in order to recuperate from one of these episodes. After six years, Mendel graduated from the Gymnasium in 1840, and he then attended the Philosophy Institute at the University of Olmutz. However, this was a financial struggle, since his parents were unable to pay for the tuition. In order to cover the expenses, Mendel tutored and his sister gave him a part of her dowry. It was in this way that Mendel was able to put himself through university. Nonetheless, upon graduating from the university in 1843, Mendel still struggled with stress and reoccurring depression, which made it difficult for him to find a job.3

Unable to find a job, Gregor Mendel was broke, and he had a hard time covering his finances after university. It was during this time that one of his previous professors recommended him to join the same Augustinian monastery he had lived at. Mendel saw the Augustinian’s commitment to education, and felt that this would be a good way to obtain a livelihood, so in 1844 he joined the Abbey of St. Thomas, an Augustinian monastery.4 The focus of the Augustinians was to serve the community by spreading God’s love, which they did through active music ministry and teaching the truth through education. Although Mendel was not strongly religious, he found a supportive home in the monastery because he was able to continue pursing his love of education.

However, his service came with several disappointments. In 1848, soon after joining the abbey, Gregor Mendel was speedily ordained a priest, since an infection the previous year had killed three of the abbey’s priests. For this same reason, at the extremely young age of twenty-six, he was given his own parish to run. However, his inability to deal with stressful situations once again became a problem, since he could not mentally handle his priestly responsibilities, such as visiting ill patients in the hospital. Due to a lack of proper training and a frail mental state, Mendel was declared unfit to be a parish priest only one year into his tenure.5 The abbot of the monastery then assigned Mendel as a substitute teacher in a local grammar school. This was a job that Mendel enjoyed and was good at, so he tried to make this a permanent position by becoming a teacher. The only way for him to do this was to obtain a teacher certification. He took the test twice, once in 1850 and once again in 1856, but failed both times due to his nervousness.6 Since he proved no good at being a parish priest, and was unable to earn a teacher certification, in 1856 he was placed in charge of the monastery’s garden, and this is what led to his famous pea plant experiments.

While cultivating the garden, Mendel chose to study the inheritance of seven traits in the pea plants he was growing. For each trait, Mendel would cross two plants with different phenotypes, which are distinct physical appearances. He would then record the results, and then cross the resulting plant again, but with itself. One trait that Mendel studied was flower color; pea plants can have either purple flowers or white flowers. In his classical experiment, he crossed two true breeding plants, meaning plants that always yielded the same trait, such as one that would always yield purple flowers (RR) and one that would always yield white flowers (rr). Mendel found that all the offspring from this cross had purple flowers (Rr), but when he allowed these purple flowering offspring to self pollinate, the offspring displayed both purple and white flowers. Although there was a much higher frequency of purple flowers, it was surprising that the trait for white flowers reappeared, since the parents had purple flowers.7

Unlike scientists during this time, Mendel chose to take a statistical approach for analyzing his data. Most scientists would perform such an experiment, record qualitative observations, and then search for a pattern. On the other hand, Mendel decided to take quantitative measurements of his experiments, counting and recording the results of each cross. He then used the data to perform calculations. Mendel performed these crosses from 1856 to 1863, and in 1866, Mendel finally published his findings to the scientific community.8 In his paper, he talked about dominant versus recessive traits, with purple flowers illustrating dominance over white flowers. These traits were controlled by alleles, which is one of the two or more alternative forms of a trait. He also established the 3:1 ratio, which states that when two heterozygous plants are crossed (Rr x Rr), the dominant trait is present three times for every one time the recessive trait appears. In addition, he explained the laws of independent assortment and segregation that state each parent only gives their offspring one out of two alleles for each trait and that during the formation of eggs and sperm, different traits assort independently of each other.9 During the mid-nineteenth century, the mode of inheritance accepted by the scientific community was known as the blending theory; that is, an offspring’s appearance is a blend of their parent’s traits. However, Mendel proposed the particulate theory of inheritance, which states that genes are passed from parent to offspring with no blending. Since Mendel’s findings were not in line with expected modes of inheritance, his work was overlooked, and his theories were not further investigated.

Two years after publication, Mendel was promoted to abbot of the monastery. His new position did not allow him the time to perform further experiments, since he was occupied with administrative duties. Then a few years later, in 1874, Mendel got into a major dispute with the government about the taxation of the monastery. He refused to pay the new taxes imposed on religious houses by the government, and he even allowed goods from the abbey to be seized instead of submitting to the tax. This battle continued until 1884 when Gregor Mendel passed away from Bright disease, better known as chronic nephritis, or extreme inflammation in the kidneys. This inflammation can then lead to heart and kidney failure, which is how Mendel died. His opposition to the government detracted from his popularity in the monastery, which is why upon his death, Gregor Mendel’s fellow friars burned his papers. They did this in an effort to purge the monastery of all the negativity attributed to Mendel and his long dispute with the government. Unknowingly, the brothers destroyed some of the most important documents in scientific history, since along with Mendel’s documents regarding the abbey, they also burned almost all of Mendel’s recorded research.10

Lucky for Mendel, his work was rediscovered in the 1900’s by three botanist. These botanist, Erich Tschermak, Hugo de Vries, and Carl Correns, conducted an experiment similar to Mendel’s and they obtained the same results. It was only after obtaining these results that they realized that Mendel had already discovered the laws of inheritance that they were just then proposing. After this event, Mendel’s work became well known and adopted, thus earning him the title, “father of modern genetics.” Nonetheless, just as his life was full of hardship and disappointment, so is his legacy. Upon further examination of his experiments, scientists have found that the data Mendel reported is really good, almost too good.11 This has caused some to label Mendel a fraud. Nonetheless, the significance of Mendel’s experiments and findings cannot be overlooked. Although Mendel’s data might have been slightly tweaked to yield more precise numbers, he did discover the 3:1 ratio and the particulate theory of inheritance. Since the publication of his work, many experiments have been done by various scientists. The conclusions have been the same, proving that Mendel’s theories were not just fabricated. Overall, Gregor Mendel’s his life was, to him, a failure, but his findings and contributions to the scientific community are remarkable.

- Simon Mawer, Gregor Mendel: planting the seeds of genetics (New York: Abrams, in association with the Field Museum, 2006), 89. ↵

- Mauricio De Castro, “Johann Gregor Mendel: paragon of experimental science,” Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine no. 4 (January 2016): 4. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Gregor Mendel,” by Shakuntala Jayaswal. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Gregor Mendel,” by Shakuntala Jayaswal. ↵

- Mauricio De Castro, “Johann Gregor Mendel: paragon of experimental science,” Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine no. 4 (January 2016): 6. ↵

- Simon Mawer, Gregor Mendel: planting the seeds of genetics (New York: Abrams, in association with the Field Museum, 2006), 41. ↵

- Alain F. Corcos, Gregor Mendel’s Experiments on Plant Hybrids: A Guided Study (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1993), 90. ↵

- Iris Sandler, “Development: Mendel’s legacy to genetics,” Genetics 154, no. 1 (January 2000): 7. ↵

- Alain F. Corcos, Gregor Mendel’s Experiments on Plant Hybrids: A Guided Study (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1993), 161. ↵

- Mauricio De Castro, “Johann Gregor Mendel: paragon of experimental science,” Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine no. 4 (January 2016): 7. ↵

- Walter W. Piegorsch, “Fisher’s Contributions to Genetics and Heredity, with Special Emphasis on the Gregor Mendel Controversy,” Biometrics no. 4 (1990): 915. ↵

65 comments

Destiny Renteria

I never knew who Gregor Mendel was until this article came about. But it is great to know that he had a huge influence in science, specifically genetics. It became something new for me to learn and now go tell others about. Overall it is a well written article, and I appreciate the work he has done. Unfortunately he did pass, but we still have his great research.

Gloria Baca

I really enjoyed learning about George Mendel. Mendel made one of the most important discoveries in scientific history yet, was not recognized. His research was thrown away almost as if his scientific discovery was of no use which is extremely sad. It was interesting to learn about George Mendel’s life and the kind of experiment he took. Though his death was a tragedy I’m glad the world now knows that his research was important.

Maria Mancha

I am familiar with his pea plant experience however I never knew much about the man behind the experiment. It was really interesting to learn about Gregor Mendel. I hadn’t really heard about him since I was in about 6th grade, so I also liked how you included an imagine of the experiment. His death was really sad and I had no idea he had Bright disease or even what that was. Its even sadder to hear his brother destroyed (not intentional) a lot of his hard work and research. He was different from most scientist. Therefore it was a very well written and interesting article, also I’m really enjoyed learning about the life of Gregor Mendel.

Marlene Lozano

Mendel made one of the most significant discoveries in science history but was not able to get the recognition he deserved. I was surprised to find out that most of his papers and research was burned just because his fellow friars tried to purge the monastery of all the negativity and Mendel’s dispute with the government. Overall this was a great article.

Johnanthony Hernandez

Great article, I remember learning about Gregor Mendel when I was in middle school. At the time we didn’t learn much other than who he was and how he influenced modern genetics and its research. But didn’t go into much detail other than that. It was interesting to learn more about him and more about his work in genetic research.

Saira Castellanos

I always wondered about these kinds of mistakes in sciece. LIke i am sure that most findings are completely by accident. Gregor Mendel, I bleive, is the most important scientist in all of science. With out him we dont know when someone else would have discovered out DNA or if anyone ever would. It’s so sad that so many people didnt get to live to see a successful life. Gregor had to go thorugh a hard time through his education, and he didnt get the recognition he deserves.

Noah Laing

Mendel’s discovery of the theory of inheritance has changed the history of science forever. The fact that Mendel suffered from issues like depression and even self doubt, shows how hard he was on himself throughout his life. I knew of Mendel’s findings before reading this article, but I wasn’t aware of any details regarding Mendel’s life and how he came to find the theory of inheritance, which made this a well written and informative article to me.

Destiny Leonard

Great article! when I first began to read the article I did not expect to enjoy it, if I am being completely honest. However as I began to read the article I enjoyed reading about Mendel’s life and his findings. It was surprising for me to discover that he was in a religious order. In the past when we covered the discoveries of Mendel in classes we often only focused on his findings and not his life or background. I enjoyed reading about his life and what were the details which lead to his discoveries. overall great job.

Rafael López-Rodírguez

I think this could be another story of conflict in a way related to church and state. But I have not heard of the story of father Mendel before and his passion for science. His contributions would be a big discovery for modern science and change the way people think and view things. Sad to read that he died thinking is work would be useless. If he would have been alive today I believe he would have received many awards towards his contributions to science.

Natalia Flores

I can’t believe Gregor Mendel thought he failed in his life even though he was the “father of modern genetics”. I had no idea that Mendel suffered from chronic depression and what sounds like severe anxiety. This led to serious problems in his life, especially when he was trying to get a job and when he was in school. On the other hand, it also showcases how mental health can be just as debilitating as a physical condition and how he pushed through it to discover the theory of inheritance.