This article examines the question concerning the annulment of the marriage of King Henry VIII of England to the Infanta Catherine of Aragon, his first wife. Henry and Catherine had a good marriage until 1525 when the Queen was told that she could bear no more children. Henry needed a male heir to stave off a civil war in England. Henry sought an annulment to marry a suitable wife to provide the heir. This article looks at who might be at fault for the failure of the ensuing annulment, the eventual divorce, and the founding of the Church of England with Henry VIII as the head of that Church. My position is that the blame for failing to gain the annulment lies with either Pope Clement VII or with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, or a combination of the two, based upon my own research, examining the views of historians of Tutor England and numerous documents related to the matter.

The three most valuable contributions to the scholarship on Henry and Catherine were written by David Starkey, Lady Antonia Fraser, and Alison Weir.1 They all three disagree with each other on numerous details. All three of their works were supplemented in my research with primary sources, including a book on the correspondence of the Emperor Charles V to his ambassadors to the courts of England and France.2 The correspondence lends credence to my position in that it shows both the Emperor’s attitude towards the two other great monarchs of the period, Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France, as well as his concern for his aunt who was Catherine of Aragon. Historians also claim that Pope Clement was acting to protect his family, the Medici, as well as acting so as not to offend Charles V, who had made him a political prisoner.3 Some modern historians and writers claim that Henry could have avoided the annulment problem by naming his bastard son Henry Fitzroy as his heir and marrying him off to the Princess Mary. I have yet to find any documents that support the concept that the Catholic Church or the English people would have supported such a solution, only the rumor shown below. In it, Antonia Fraser discusses the concept of a papal dispensation allowing the marriage, which, of course, would be going against canon law, as I will discuss.

We might first want to answer the claim that Henry VIII could have produced a male heir by allowing Henry Fitzroy to marry the Princess Mary. Antonia Fraser addresses this claim in her book:

“Some clumsy efforts were evidently made by the King’s advisers to cope with Princess Mary’s ambivalent situation. One of the most extraordinary—yet it seems to have received tacit papal approval—was the weird Pharaonic idea that half-brother and -sister Princess Mary and Henry Duke of Richmond should be married to each other. This was against canon law (as well as against natural law in most civilizations). Yet the Pope seems to have been inclined to grant a dispensation for such a marriage, on the condition that the King would abandon his project of divorce, showing how far the supposedly strict laws of affinity could actually be stretched. Cardinal Campeggio mentioned the subject in a letter to the Pope’s secretary of 17 October…. but I do not believe this plan would be sufficient to remove the chief desire of the King.”4

At the time that the royal physicians notified Catherine and Henry that the Queen would have no more children, which Allison Weir places in her chronology as being early 1524,5 the marriage had already survived the birth of Henry Fitzroy in June of 1519,6 the baby’s christening having been attended by both Cardinal Wolsey and Queen Catherine.7 According to Antonia Fraser, the Queen had no problems with Henry Fitzroy being born, as she expected to have a male child of her own soon.8

In researching Henry and possible causes, I read both David Starkey’s book Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII as well as Antonia Fraser’s The Wives of Henry VIII. Both Starkey and Fraser agree that Henry was a staunch Catholic until the time of the annulment, and in some ways thereafter. It was hinted that Catholic monarchs would not divorce their spouses. More likely, they would get a papal annulment, as did the King of France in 1503, or they would find cause to insure the unwanted spouse’s death. Both authors discuss Henry being betrothed to the widow of his older brother Arthur, the Prince of Wales and the heir of Henry VII. Both Starkey and Fraser discuss the fact that Catherine’s parents, Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, were the heads of one of the three most powerful kingdoms in Europe and married into one of the other two kingdoms. Both authors also mention the dynastic family-building of Ferdinand and Isabella by their having Catherine’s older sister Juana marry the Archduke of Austria, Philp, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. Because of Philip’s early death and Juana’s mental illness, their child (Catherine’s nephew Charles) at the time of the annulment was the King of Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Holy Roman Emperor. And both authors say that there was no question of Catherine being a suitable wife for a Prince of Wales or an English King. She was educated by possibly the most educated monarch in Europe (her mother Queen Isabella). Despite affairs on Henry’s part, there was no talk of an annulment until her latest miscarriage and the English royal physicians saying she would bear no more children (creating the need for the annulment since a male heir was necessary for the continuation of the Tudor dynasty and the prevention of a civil war).9

One secondary source that points the blame away from Henry is an article on the psychology of the King written by Miles Shore in 1972. Shore states:

“Why did the infatuation for Anne Boleyn develop when it did? At the time Henry VIII started proceedings for the annulment he had been married to Catherine for seventeen years, officially, if not always faithfully. And Anne Boleyn had been at court—and thus available to Henry—for at least three years. Henry had already had an affair with her older sister before their relationship began.”10

Shore asks then answers:

“Why did Henry continue to pursue Anne Boleyn for seven years against the opposition of his closest advisers, the Pope, his own subjects, and most of Christendom? Henry himself explained the wish for a divorce from Catherine of Aragon as the product of a guilty conscience at having married the widow of his elder brother Arthur.”11

The article also states that most historians have explained the desire for the annulment as the dissatisfaction of a thirty-five-year-old king whose forty-one-year-old wife had not borne him the son he needed to ensure the royal succession. Shore tells us that Henry had an affair that resulted in the birth in 1519 of Henry Fitzroy, and another affair with Anne Boleyn’s older sister, as mentioned before:

“A male heir, of course, was exceedingly important, not only to Henry as a Tudor, but also to the whole country. Its national significance could not have helped but to intensify its personal meaning, for a disputed succession could reopen the terrible struggles of the Wars of the Roses, which the Tudors had settled. But even that might have been avoided by other arrangements: for instance, the marriage of Princess Mary, his daughter by Catherine of Aragon, to her cousin James V of Scotland, or to Henry Fitzroy… Of thoughtful historians, only [scholar Lacey Baldwin] Smith has suggested that Henry’s offended conscience might really have been important.”12

Shore offers his analysis of Henry and his behavior as king as well as explaining his behavior during the annulment by his discussion of Henry’s “alter rex,” or Henry’s series of senior mentors and advisers. Catherine of Aragon was the first person upon whom he leaned as an adviser following the death of his father. Thomas Wolsey would follow in that role until his failure to obtain the divorce for Henry, as well as his mismanagement of government. Shore also goes deeply into the trust Henry had in Wolsey, despite the fact that Henry was very capable, and with Catherine as his mentor, able to run England very efficiently. The article implies that Wolsey overstepped his power and paid for it in 1529 when his enemies saw their chance to discredit him. The article also explores Wolsey’s enormous ego.13

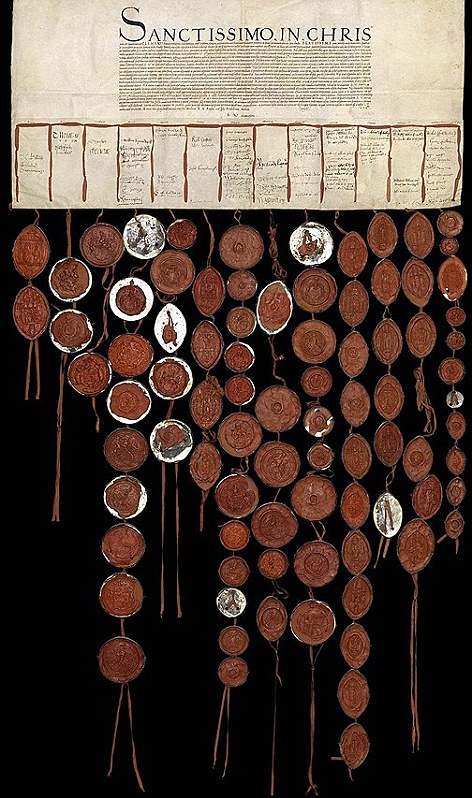

One of the strongest pieces of evidence as to why Henry VIII needed an annulment, which strengthens my thesis, is the letter from the English Parliament to Pope Clement VII, illustrated in the featured image of this article. It is likely dated June 12, 1530. It bears the seals of eighty-one members of the English Parliament and Catholic clergy. The members of Parliament whose seals are affixed to the document account for seventy percent of the sitting House of Lords, as well as a vast majority of the Catholic bishops and archbishops, with the exception of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who, at that time, was known to be in sympathy to Catherine. This is noted by both a Reuters report as well as David Starkey. The letter itself illustrates the fact that Henry had taken counsel with his Lords and convinced them that the annulment was necessary to prevent a civil war, since there was no male heir to inherit the throne of England. The letter was released from the Vatican Archives in 2009.14 At that time, no other documents exactly like it were in the United Kingdom to suggest its existence.

It is the Vatican that claims that the language of the petition asking for the annulment is threatening. But that would be a signal that Henry was not to blame. Most historians would agree that Henry VIII could not have gotten Parliament to send a letter to the Pope asking for a divorce by his own power, especially one threatening the Pope, who supposedly was under the protection of the Holy Roman Empire. Most historical sources claim that the Tudor and Stuart monarchs ruled by consent of their lords.15

To further illustrate the differences between the papacy and the conduct of Henry and Catherine, and to show why it’s not likely Henry or Catherine who originally caused the annulment to fail, we need only look at this information from a multi-volume book on the papacy:

“The separation of England from the Holy See was not like that of Germany, the result of a combined movement of the common people and the learned classes…. The separation was favored by the ecclesiastical and political development of the nation, which since the fourteenth century had begun to slacken its ties with Rome. The dependence of the clergy on the throne had already become close under the first Tudor, Henry VII…who in 1485 not only ended the War of the Roses, in doing this had started the beginning, especially for England, of a new epoch. Henry VII resembled in character Ferdinand the Catholic.”16

Martin Luther’s new doctrine had found adherents in England. Cardinal Wolsey had been comparatively lenient in his punishment of heretics towards Catholicism. The English King in recompense for his book condemning Luther had been named a “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X.17 As mentioned earlier Henry had been married off to his brother’s widow over his objections but at the desire of Henry VII and Ferdinand of Spain. Pope Julius II had issued a papal bull granting the dispensation from the obstacle of marriage. Catherine was five years older than Henry, but from the first, the marriage appeared to be a perfectly happy one.18

Five children, three boys and two girls, were born, but the only one who survived was Mary, born in 1516. The queen bore the successive losses with Christian resignation. And as early as 1519, the hope of a male heir had vanished, according to some. As early as 1519, Henry had adulterous relations, with Elizabeth Blount (the mother of Henry Fitzroy), and later with Mary Boleyn (the sister of Henry’s second queen). Yet so little did divorce occupy Henry’s mind that in 1519, he commissioned a Florentine sculptor to execute a common tomb for himself and Catherine.19

In transitioning from looking at Henry VIII to Pope Clement VII and to Charles V, we need to look at the other reason Henry could have legally been free of Catherine under canon law. Historically, most historians have been featuring Henry claiming his marriage to Catherine was against canon law based upon biblical teachings from the book of Leviticus and his consanguinity to Catherine. Consanguinity was the issue that Pope Clement VII was rumored to overlook in the case of Henry Fitzroy and the Princess Mary. But Henry and Catherine, according to church law, were first level consanguine. It would be considered the same thing as marrying his sister. And yet there had been a papal dispensation allowing Henry to marry Catherine. This was brought about because both Henry VII and King Ferdinand of Spain wanted the alliance.20

The case against the marriage was narrated by David Starkey:

“The King thought that it would be easy. For the facts of the case, as they presented themselves to him, were obvious…. Unlike the rest, he had come up with an answer from the Word of God. If a man shall take his brother’s wife, it states in Leviticus, it is an impurity: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless…But what of the papal dispensation which had been obtained for the marriage? Was that not sufficient? Since the dispensation had been powerless to ward off the curse of childlessness (in this case male childless), it was clear the Pope had erred in granting it…Julius had been wrong. Henry had suffered for that wrong. Now Julius’s successor, Clement VII, must right it.”21

This by itself would form the basis for saying that the fault laid somewhere besides just Henry VIII. Catherine was the widow of Henry’s older brother, the Prince of Wales. All Henry needed to do under canon law is prove that his brother consummated the wedding, for which there were many witnesses in the royal household. This would imply the unwillingness of the reigning pope to grant the annulment. Many historians back the claim that the wedding between Arthur and Catherine had been consummated, including Fraser.22

T. C. Price Zimmermann appears to leave this failure directly upon Clement VII. Zimmerman states:

“In their estimates of Clement VII’s character modern historians have generally agreed with criticisms made by the pope’s contemporaries. In regard to his timidity, his vacillation and his irresolution bordering on deviousness, scholars such as Pastor, Pollard, Mattingly, and Hughes have come to substantially the same conclusions… By diplomatic ambiguity and procrastination, it would appear, the pope attempted to conceal what was in reality an habitual indecisiveness…. ‘The pope sees all that is spoken sooner and better than any other,’ complained Gardiner, ‘but no man is so slow to give an answer’…. Varchi, rather more bluntly, called him a ‘simulator and dissimulator.’ Such qualities did not make for a commanding presence. And the historian Francesco Vettori was only expressing the prevailing opinion in his epigrammatic summary of Clément’s career: ‘He endured an enormous labor to become, from a great and respected cardinal, a small and little-esteemed pope.”23

In his book Emotion in the Tudor Court, Bradley J. Irish devotes a chapter to “The Disgusting Cardinal Thomas Wolsey.” There seems to be some difference of opinion between Irish and Zimmermann on the subject of Clement VII. Zimmerman quotes sixteenth-century historians as saying that Clement was indecisive and played politics over his duty to defend the faith. This book at least hints that perhaps Henry VIII and Charles V both had motives that had nothing to do with the biblical justification of annulling Catherine’s marriage to Henry, and that perhaps the pope could not grant the annulment because of undue pressure upon himself and the papacy from Charles V. The book mentions both the relationship between Catherine and Charles as well as the Emperor’s power in European affairs.24

Fred Dotolo is kinder in his scholarly article on Clement:

“A historian once ended his work on Clement VII (r. 1523-34) by stating, ‘No pope ever began so well, or ended so miserably.’ True enough in the sense that most contemporary observers were more thankful than mournful at Clément’s passing. However, one might also see in his papacy a vigorous defense of papal rights against the growth of monarchial power, a diplomatic and even pastoral struggle to retain the ancient division within Christendom of the priestly and kingly offices.”25

“During the late Renaissance, the Church faced the danger that competing dynastic claims over Italy would reduce the papacy to a simple plaything… The early sixteenth century popes resisted this call because the memory of the last time councils and popes clashed over the issue of conciliarism.… Similarly, they feared that the monarchs might use the need for reform to seize greater control over their national churches…. This was the papacy Clement had inherited.”26

Clement VII was born Giulio de ’Medici in 1478, an illegitimate son. Political violence claimed his father just prior to Giulio’s birth. This is a factor in his public behavior. Historians remark about his defense of his family coming before his rule as pope. The Medici were one of Italy’s most power families. They and the Borgia family account for several of the sixteenth-century popes. It seems to be an accepted concept that Clement VII put the safety of the Medici above the church after his imprisonment by Charles V.25

Another important source when considering fault is a book written in the mid-nineteenth century (1850 to be exact), Correspondence of The Emperor Charles V (editor William Bradford). Even so, it is still considered one of the best historical references on the topic of sixteenth-century politics and the behavior between the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, his ambassadors to England, and King Henry VIII. It was most recently reprinted in 1971.

His ambassador to England wrote in December of 1521 that it might be best for both the Empire and for England to both back Thomas Wolsey as the next Pope, or the Medici cardinal (the man who actually will become Clement VII).28 The ambassador will later complain of the excesses and power grab attempts by Thomas Wolsey as the Archbishop of England.29

What the correspondence also does, when read carefully, is to illustrate that England, the Holy Roman Empire, and Spain (the last two at the time of the annulment headed by the same person), were all as involved in politics as much as they were the issue of the ecclesiastical position of the marriage between Henry and Catherine, or in the case of England, the need to prevent a civil war, which is of course a political action.

Chapuys (the second ambassador to England) complained of Wolsey. He referred to Anne Boleyn as “the lady” and Catherine as “the Queen” while reminding Charles that the Queen is his beloved aunt.30

Nowhere in what I have read of this book does it say that if Catherine had been the sister of a German elector (like Anne of Cleves) instead of his aunt that Charles would have opposed the annulment. The first ambassador also wrote to Charles about what a good son of the faith Henry was and what a good ally of the Empire. It is only after Henry both considers siding with Francis I, the King of France, and divorcing Catherine that Charles seems interested in interfering in papal business.

The correspondence also makes it clear that Charles had interfered with the annulment because of the Queen being his aunt and to retaliate against Henry for befriending Francis I. Never does the correspondence say that Henry was contemplating breaking with the Catholic Church until Clement VII threatens excommunication unless Henry denounces and puts away Anne Boleyn. Nowhere does it say that Charles is concerned about keeping England Catholic or the possibility of the action that Henry will take, which will be to follow the lead of the German electors and turn England Protestant. This is illustrated later in the Correspondence in a section on the Emperor’s attitudes towards others, such as towards the Pope and the Kings of France and England.31

After reading more than I believe three thousand pages in researching this question, I feel comfortable in assuming that given the evidence that Henry VIII and Catherine had a good marriage, that Henry had a roving eye which his devout wife ignored, that the toll of attempting six or more pregnancies had decimated Catherine’s body, that if Prince Henry (their first child) had survived, the divorce would have been unnecessary, and that the boy would have ruled as King Henry IX.

In a final note, the annulment was to prevent a civil war. Henry needed a male heir. Two separate historians mention that if the child Anne Boleyn miscarried (a boy) on the day Catherine was buried had lived, then Henry would not have had the courage to have had her executed. Losing the child sealed her fate. As Alison Weir reports: “But the damage had been done. That evening, Anne aborted a fetus of about fifteen weeks that had all the appearance of a male. ‘She has miscarried her savior,’ wrote Chapuys.”32 Starkey reports it as this: “For on the day of the funeral, Anne miscarried. The fetus, Chapuys reported ‘seemed to be a male child which she had not borne three and a half months.'” Court opinion said this was likely the end of the second marriage.33

- See David Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (New York: Harper Collins, 2003); Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992); and Alison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Grove Weidenfeld,1991). ↵

- See William Bradford, Correspondence Of The Emperor Charles V (New York: AMS Press. 1971). ↵

- See Fred Dotolo, “Priest and Prince: Clement VII and the Struggle of Church and State in the Renaissance,” Verbum Vol. 5, No. 2, Article 23. ↵

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 151. This is the source that Antonia Fraser uses for the above entry: “Towards the end of the eighteenth century, in refusing the petition of a man from the diocese of Liege to marry his half-sister, by whom he had had twin children, the Sacred Congregation of the Council stated that it was disputed whether unions in this degree were forbidden by natural law, but that the popes seemed to think that such was the case, since they had never allowed it. However, one of the two cases adduced of such a request actually having been made and refused was that of Henry VIII of England, who allegedly asked Pope Clement VII to allow his daughter Mary to marry his natural son, Henry Fitzroy, the Duke of Richmond; this was cited on the authority of Antoine Varillas. But it is doubtful that the request was ever formally made, much less formally refused. When the Anglican Gilbert Burnet challenged the authenticity of this episode and demanded evidence, Varillas cited vaguely the correspondence of Cardinal Campeggio. Campeggio, however, seems to have mentioned this subject only once, in his letter of October 17, 1528, to Jacopo Salviati, the pope’s secretary. Cardinal Wolsey, he wrote, told him that ‘they have thought of marrying her (the king’s daughter) with a dispensation of His Holiness to the natural son of the king, if it could be done.’ And far from opposing the plan in principle, Campeggio adds immediately afterwards: ‘I too had thought of this at first, as a means of assuring the succession; but I do not believe that this plan would be sufficient to remove the chief desire of the king.’ Furthermore, he received a reply from Rome saying that the pope would be much more inclined to grant such a dispensation if the king would give over the idea of annulling his own marriage.” Henry Ansgar Kelly, “Kinship, Incest, and the Dictates of Law,” American Journal of Jurisprudence 14 (1969): 72-73. ↵

- Allison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Grove Weidenfeld,1991), Chronology ↵

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII: (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,1992) 83. ↵

- Both Weir and Fraser agree on this point. ↵

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,1992), 101. ↵

- In my use of all three of these scholars’ works on King Henry, I must credit Antonia Fraser for her superb scholarship, especially in her even-handedness and fair appraisal of her sources. ↵

- Miles F. Shore, “Henry VIII and the Crisis of Generativity, “The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972), 360. ↵

- Miles F. Shore, “Henry VIII and the Crisis of Generativity,“ The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972), 360. ↵

- Miles F. Shore, “Henry VIII and the Crisis of Generativity,“ The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972), 361. ↵

- Miles F. Shore, “Henry VIII and the Crisis of Generativity, “The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972), 365-366. ↵

- Catherine Hornby, “Vatican Secret Archives show Galileo signature, Henry VIII letter, Templar scroll,” Reuters, February 28, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUS29492079720120229 ↵

- Catherine Hornby, “Vatican Secret Archives show Galileo signature, Henry VIII letter, Templar scroll,” Reuters, February 28, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUS29492079720120229. ↵

- Ralph Francis Kerr, The History of the Popes: From the Close of the Middle Ages, Vol X (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1923), 238. ↵

- Ralph Francis Kerr, The History of the Popes: From the Close of the Middle Ages, Vol. X (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1923), 240. ↵

- Ralph Francis Kerr, The History of the Popes: From the Close of the Middle Ages, Vol. X (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1923), 241. ↵

- Ralph Francis Kerr, The History of the Popes: From the Close of the Middle Ages, Vol X (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1923), 241. ↵

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 37-38. ↵

- David Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (New York: Harper Collins, 2003), 201, 202. ↵

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 28-29. ↵

- T.C. Price Zimmerman, “A Note on Clement VII and the Divorce of Henry VIII,” The English Historical Review, vol. 82, no. 324 (Jul. 1967): 548-549. ↵

- Bradly J. Irish, ”The Disgusting Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, ” in Emotion in the Tudor Court (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2018), 23-24. ↵

- Fred Dotolo, “Priest and Prince: Clement VII and the Struggle of Church and State in the Renaissance,” Verbum Vol. 5: ISSP. 2, Article 23. ↵

- Fred Dotolo, “Priest and Prince: Clement VII and the Struggle of Church and State in the Renaissance,” Verbum Vol. 5: ISSP. 2, Article 23. ↵

- Fred Dotolo, “Priest and Prince: Clement VII and the Struggle of Church and State in the Renaissance,” Verbum Vol. 5: ISSP. 2, Article 23. ↵

- William Bradford, ed., Correspondence Of The Emperor Charles V (New York: AMS Press, 1971), 21. ↵

- William Bradford, ed., Correspondence Of The Emperor Charles V (New York: AMS Press, 1971), 264. ↵

- William Bradford, ed., Correspondence Of The Emperor Charles V (New York: AMS Press, 1971), 286. ↵

- William Bradford, ed., Correspondence Of The Emperor Charles V (New York: AMS Press, 1971), 466. The Correspondence is interesting reading, but it is, indeed, correspondence. It has no table of contents, or index; just the editorial footnotes. ↵

- Allison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (New York: Grove Weidenfeld,1991), 303. ↵

- David Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (New York: Harper Collins, 2003), 553-554. ↵

10 comments

Kelly Arevalo

Hello Christopher. Congratulations! It is a really interesting article. The amount of power that the catholic church had in that epoch never ceases to amaze me, how interconnected they were with the world powers, the monarchies, during that time. However, I can’t say I agree with you. I think it’s a little extreme to take the responsibility away from king Henry XVIII, specially considering that even it was his son edward who succeed him, his sisters were the ones to become the next monarchs. Even so, I liked how you handle the topic, good job.

Gisselle Baltazar-Salinas

I loved your article. The story of Ana Boleyn and King Henry has always interested me. I’ve asked myself the same question as the title of this article, had the King had a son with Catherine of Aragon would England had still left the Catholic Church years to come? Although I had done some research on my own about the Tudor era this article helped highlight the complexity of this era and question. I had no idea he had a tomb for him and Catherine and Ana Boleyn had a miscarriage which might have been a boy. Very insightful. Well done!

Brissa Campos Toscano

Hi Christopher! I am a fan of the monarchy story, and the life and reign of King Henry VIII is indeed an excellent example of how interesting it is. While reading your article, I found it interesting how you combined different points of view of other historians and how you relied not only on the history that is already known in history education textbooks. I did not know about the different reasons for the separation and that it was not only a love story that came with it. Thank you for letting me learn something new!

Madison Goza

I personally am fascinated by this topic and really enjoyed the opportunity to read your article. I like how straight-to-the-point the introduction is, providing a brief summary and clear stance on ultimately who you feel, based on your research, is to blame. I appreciate being walked through the sources and the addressing of rumors while also providing concrete research in order to gather the facts. You were able to simplify something so complex that it was easy to read and understand but didn’t oversimplify it that it lost its nuances. Great job!

Vianne Beltran

Hi Christopher,

I found your title super eye catching. Not only because I knew it had to do with my favorite historical subject but because it gave the subject an even more mysterious air. While I’ve learned a lot about the Tudor era since I was young, your article taught me a lot I didn’t know. I didn’t know Henry commissioned a joint tomb for him and Catherine even after he began to realize her infertility. This reinforces to me that Henry had a certain respect for her, especially since he relied on her as an advisor in his earlier reign. Your article did a good job of highlighting the complexity of the situation and all the different factors affecting it. Perhaps even if he stayed with Catherine he still would have split from the Catholic Church.

Sophia Kussel

unsurprisingly, it seems that king Henry plays a large role in the separation of the church and England. you have written a very enjoyable article!

Santos Mencio

An interesting article about an issue that seems to be often overgeneralized. The story of Henry VIII and his many wives is often chalked up to him being a tyrant in some form. However, there were clearly many more factors at play, with both the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, as well as threats of conflict and civil war played a part in the collapse of the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine.

Jaedean Leija

this article was well written , learning history of religion really is not my favorite to read about but this article did keep me informed and entertained. I have always wondered why England went from one strict religion to opening up to another religion. My wondering and questioning ended after reading this I no longer have to ask in class why that happened , this article gives you a better understanding. All the research you did to inform us reads is great and it did pay off.

Phylisha Liscano

This was a very interesting and informative article. I had very little knowledge of the subject before reading but I enjoyed getting the chance to read more about it. I can tell lots of research was put into your article and you provided lots of information. This topic doesn’t look the easiest and I applaud you for getting it done. Overall great article and an excellent topic. Good job, and congratulations for being nominated.

Elliot Avigael

It is a bit amazing to think that this whole episode began an entire schism just over King Henry wanting to divorce his wife. Even then, the story is far more complex than that. I enjoyed the article and appreciated how you got to the heart of the matter in your story.