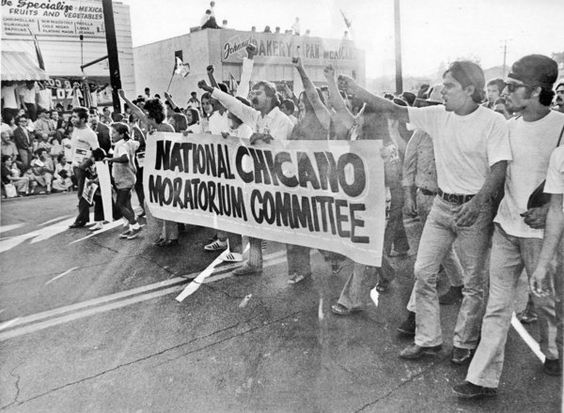

On August 29, 1970, in the midst of more than 20,000 people, news correspondent Ruben Salazar walked alongside fellow Mexican Americans covering the Chicano Moratorium March in East Los Angeles, a protest to the Vietnam War. Initially supported by the Mexican-American people, the war began to be questioned and rebuked after Chicanos began to be drafted in disproportionate amounts.1 Mexican-American men were laying down their lives for a country that did not respect them, their families, or their culture. The Chicano Moratorium brought out hundreds of spectators with the jovial sounds of Mexican music and a convivial environment.

The rally would continue throughout the day until it was abruptly broken apart by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) with tear gas canisters. Many Chicanos fought back by throwing back the same tear gas projectiles that were being used on them, and anything else that could serve as a weapon.2 Ruben Salazar had been resting in a local bar when the chaos broke out. A tear gas projectile was shot into the bar to smoke out a reported “armed individual,” hitting Salazar in the head and killing him instantly.3 News of his death was broadcast widely, and it significantly impacted the Los Angeles Chicano community, as Ruben Salazar was one of the few mainstream journalists to address and voice the needs of the Chicano Movement.

Who was this Ruben Salazar who was killed that August day? Ruben Salazar was born March 3, 1928 in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. During his infancy, his family moved to El Paso, Texas. Salazar would go on to attend school and grow to love reading in his early years. Upon graduating from high school, he enlisted in the army and served for two years after becoming a naturalized citizen.4 With the G.I. Bill supporting him, Ruben Salazar attended Texas Western College and graduated with a bachelor’s in journalism in 1954. He then went on to become an investigative journalist for El Paso Herald-Post. Ruben Salazar’s work paid off, and he obtained a position at the LA Times, becoming the first Mexican-American journalist to have his own column.5

Much as many other immigrants, Salazar grew up in between two very distinct cultures. Refusing to be defined by his ethnicity and background, he became successful through his perseverance. Although many characterized him as a cosmopolitan man with worldly views, he kept himself grounded by never losing sight of where he was from. After working at the Los Angeles Times for eleven years, he left his position to become a news director for KMEX, a Spanish-speaking news station in Los Angeles, California.6 Ruben Salazar understood that he had a privilege and a voice in the media that others did not, and so with the help of his new position, he began to shine a light on the troubles the Mexican-American community had to face, such as police brutality and racial discrimination especially in East Los Angeles.7 It became common knowledge that Salazar and the LAPD did not get along very well, due to his high intrusion into political matters and his exposure of the LAPD’s efforts to diminish the Chicano movement. He became renowned for his investigative tactics and for his unwavering courage, which he demonstrated when obstacles came his way.

His untimely death did not silence the Chicano movement; rather, Salazar became a martyr for his people. After his death the Chicano Movement gained momentum. Ruben Salazar was not an activist nor a leader in the Movement, but he addressed the basic needs and frustrations expressed by the people through his writings. He was the example of the American Dream, a symbol that progress was possible. Ruben Salazar’s legacy left behind a definition to what it meant to be a Chicano and strengthened the pride behind being one.

- Ruben Salazar and Mario T. Garcia, Border Correspondent: Select Writings, 1955-1970, ed. Mario T. Garcia (California: University of California Press, 1996), 1-2. ↵

- Ruben Salazar and Mario T. Garcia, Border Correspondent: Select Writings, 1955-1970, ed. Mario T. Garcia (California: University of California Press, 1996), 2-3. ↵

- Edward J. Escobar, “The Dialects of Repression: The Los Angeles Police Department and the Chicano Movement,” Journal of American History 79, no. 4 (March 1983): 1483-1484. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “Ruben Salazar,” by Ewing Jack. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “Ruben Salazar,” by Ewing Jack. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “Ruben Salazar,” by Ewing Jack. ↵

- Edward J. Escobar, “The Dialects of Repression: The Los Angeles Police Department and the Chicano Movement,” Journal of American History 79, no. 4 (March 1983): 1486-1487. ↵

30 comments

Cameron Ramirez

What an interesting and great article! You brought up some interesting points and it made total sense. I didn’t really know much about Ruben Salazar. Thanks to your article I now know a bit more about this amazing and successful man. It is sad how he was not able to see it through. Anyways, good article I hope to read more great articles from you because it was a good read.

Erik Shannon

This was a very interesting article. This article was very descriptive. I did not have any previous knowledge on Ruben Salazar before reading this article. I did not know his life and his role had such an impact on the Chicano movement. It is crazy how he died and did not get to finish out his life. Overall, this is a very good article.

Deanna Lummus

Awesome article. I never knew anything about him. His name was familiar but I had no idea what he was really known for. Journalist can really make or break movements like this. I wonder what would have happened if he had never existed. Would this type of movement even be remembered? This article was very clear and concise enough to where I could completely understand what happened with out getting confused. I have always been curious about investigative journalism. I didn’t realize people even went to school for it.

Alejandra Mendez

I’ve heard of these rallies before but never really looked fully into them. Now that I know more about it, it’s astonishing and admirable what everyone did to voice their opinions. I don’t believe it was fair either for Mexican-Americans to be drafted and sent off into a war to fight for a country that did not respect them. It is somewhat shameful that the U.S. would even do that. It is even more shameful that you could probably still argue that a lot of minorities to this day are fighting for a country who still does not fully respect them.

Alexis Renteria

Very well written article. I think its crazy how one of the tear gas canisters that were being thrown hit Salazar in the head and killed him while he wasn’t even being involved in the movement. However, it makes sense that Salazar’s demand for change and shining light on the problems chicano and Hispanic people were facing could get him in trouble with people that disagreed with his opinion. Overall, this article shows how Salazar did a well job of showing people how Hispanic and chicano people were being treated unfairly and the things they had to do to change that.

Mark Martinez

An extremely well written and put together article. Ruben Salazar sounded like an amazing strong person and I wish I knew more about him. To ignore the differences in people’s background and just work hard to do something he loved. It is a tragedy he became a type of martyr for the voices of his fellow Mexican Americans but hopefully his death was a painless one.

Justin Garcia

This was a very well written article. The fact that police would break apart peaceful protest is alarming. They simply were using their rights given by the first amendment but the police saw it fit to ignore the rights. The method to break up the protest was very excessive using force and tear gas as if the protesters were violent and unpredictable. This article overall shows that fighting for change will always have risks but we should never stop fighting for a good cause.

Morghan Armenta

So glad to see an article on the Chicano movement here on the blog, this is amazing. I think that this was also a very momentous part of the civil rights movements happening during the Vietnam War even though they aren’t given as much attention. Ruben Salazar is someone who fought peacefully for his peoples rights through his journalistic talents. Awesome article, I enjoyed reading this one, thank you.

Thomas Fraire

This was a very well written article, but coming into it I had no idea who Ruben Salzar was. Nor did I understand the impact he had on the Chicano movement. This article was very short, and to the point, I wish that it was expanded on just a little more but over all it was very solid, great job.

Osman Rodriguez

Great article! Concise and straight to the point. It is a very well written article, and contains a substantial amount of information about Ruben Salazar. I personally, had no prior knowledge when it comes to Salazar. I didn’t know the significance he had on the chicano movement and the key role he played in it. He seemed to be a successful man, destined for greater things. It is unfortunate, what had happened to him.