In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, during the Genroku Era, Lord Asano Naganori, was one of the many daimyo who got invited to the Shogun’s palace in Edo to entertain the Imperial Envoy. Asano knew little about proper etiquette. So to make sure he was well prepared for the ceremony, Kira Yoshinaka was chosen by Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi to educate Lord Asano, as he was an expert.1 Asano and Kira did not get along, as they had many disagreements. Kira would often embarrass Asano for being a Lord and yet not knowing the manners of the upper class. He even demanded a bribe for his teachings, which was denied, as Asano thought it was his duty and not a favor. Kira took offense to the response, as he thought it was well deserved for the trouble. Although there were many disputes, Asano had decided to remain calm, and he proceeded with the lessons.

Right before the ceremony, Kira deemed Asano’s gift as trivial and described the lord as being similar to a country boor with no manners. Being pushed over the edge, Lord Asano drew his sword and struck Kira across his face, wounding him. After being pulled apart, Asano was ordered to commit seppuku, honorable suicide, as any violence against a man within the Chiyoda Castle was forbidden, especially if it was against a higher official.2 When questioned about the incident, Asano responded that he regretted not killing Kira when he had the chance, before killing himself to protect his honor.

On February 4, 1701, Asano Naganori, Lord of the Ako Domain, and the Lord of the Yoshida domain were both invited by the Shogun to host a ceremony.3 The New Year’s greeting ceremony was held at the imperial court located in Kyoto. This was an important event, as the Shogun would be in the presence of the emperor, along with the retired emperor.

Kira Yoshinaka was a koke, knowledgeable in ritual etiquette, who acted arrogantly towards Asano through his endless insults, resulting in the foregoing incident. The Bakufu, responsible for making judgement calls and punishments, not only condemned Asano to seppuku, but ruled Kira as innocent. Not only was Kira free from any charges, but was approached with sympathy. The Bakufu then asked a bystander whether Kira had reached for his sword at any time during the fight. Denying the accusation, Asano was then sentence as he “acted in the most insolent manner,” being placed in the custody of Tamura Ukyo-daibu around 1 pm.4 After some investigations, the execution was carried out after 6 pm.5

News quickly got back to the Ako Castle about what had happened. The samurai, who were then Ronin, grew angry, and knew, as a loyal samurai, something had to be done. Ōishi Yoshio, the leader of Ronin, had decided a secret oath to seek revenge, resulting in the remains of 47 Ronin out of Asano’s 300 samurais. Knowing that the estate would be taken over, Ōishi suggested a peaceful surrender. On March 17, Asano’s Edo Estate was confiscated along with his land and castle on March 26.6 Realizing that the Ako Estate would never be restored, they started plotting their revenge.

The loyalty a lord has with his samurai was something Kira understood very well, as they swear an oath to serve and protect. Fearing an attack, Kira soon became paranoid, resulting in an increase of guards and house arrests. Ōishi knew that Kira would become weary of them, so he decided to take things slow and strike when Kira’s guard was at its lowest.

On April 12, to avoid any suspicion, Ōishi and his men decided to leave the castle.7 They went their separate ways, cutting ties with their family and friends, and living as if they had lost “all sense of honor.”8 They soon went on to find suitable jobs. Some became farmers or monks, others finding it difficult to adjust to their new life, leading them to banditry.9 After divorcing his wife, Ōishi left for Kyoto, living his life pretending to be retired.10 Knowing that Kira would keep a close watch, Ōishi knew he had to be convincing. There would be many drunken nights at the bar resulting in many brawls. Ōishi was truly at his lowest, but he knew that this was what had to be done. This routine would continue for the next two years. Kira, learning of the old samurai actions, finally became convinced enough to think that the Ronin had moved on, so much so that he began to make fun of the samurai.

Originally, the execution was supposed to take place on December 5, 1702, but after learning that the Shogun was visiting Yanagisawa’s castle, the event was moved to December 14, 1702, to correspond with their lord’s death that had taken place on March 14.11

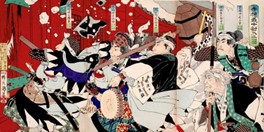

December 14 was a snowy day and the loyal Ronin had regrouped for the final time, reporting to Ōishi their findings, which they had collected from their jobs as tradesmen and workmen. One Ronin even went the extra mile in marrying the daughter of one of Kira’s workmen in order to get the layout of the mansion. They then began supplying themselves with armor and weapons before splitting up into two groups: one taking the front entrance, the other taking the back. Raiding into the mansion, Ōishi and the Ronin were met with many soldiers, but had managed to fight off the guards. Kira was then found hiding in a secret courtyard, and was beheaded using the same sword that had scored him two years prior.12 The Ronin wrapped the head in a cloth and marched back to Sengakuji Temple to Asano’s tomb. They began to wash off the bloody head at a nearby well before presenting it to Asano along with his sword.13 The Ronin then turned themselves into the officials prepared for their already foreseen fate. Admired for their loyalty, the Shogun decided to let the Ronin die by seppuku, feeling that they should die an honorable death rather than being executed. The Ronin died together and all 47 tombs were organized around their lord in Sengakuji Temple.14

Later, there were debates over whether the bakufu decision of the incident was fair. Some say that it was a violation of Kenka Ryoseibai, which states that both parties would be held responsible for the fight, resulting in equal punishment. Unfortunately, this law wasn’t working under the bakufu, as it was only a customary law and there was doubt about it being both parties, as it was Asano who lunged at Kira. There was still some speculation, as a true samurai would always stand his ground, questioning if Kira was truly innocent.15

Asano’s samurai were also ichibun, meaning private honor individually or a whole. They felt that their lords’ fight with Kira was for good reasons, and although he was no longer with them, it was their duty to carry out his mission. A dishonor to their Lord was a dishonor to them. This was their principle as “warriors” to Lord Asano. After finding out about Lord Asano’s death, the Ronin knew that simply attacking Kira’s mansion wasn’t going to be an easy task. Not only would it bring dishonor, but a repeat of Asano’s flaw. They needed to make sure that they weren’t acting on emotion, but on “rational judgment,” which would be supported to redress. Samurai were prohibited from performing this act, but there was a loophole within the law. Through the bond of the 47 Ronin, it created the “Ako retainer band,” allowing them to self-redress.16

Both incidents, the death of Asano and the attack on Kira’s mansion in Edo, later became known as the “Ako Incident.”17 This event had moved Japan, considering how it happened during the time when the stern code of warriors was decreasing, as Japan was starting to be engulfed by urban and commerical norms. The incident was made into a popular play called “Chushingura; The Treasury of the Loyal Retainers,” standing as a metaphor for “unrelenting resistance to corrupt power.”18 In 1705, there was another play where Chikamastsu carefully conducted the roles for the historical figures. This would go on to influencing the minds of all classes, as new cultural awareness was beginning to evolve.19 The story would be reinterpreted many times, making the truth become more “inaccessible” as generations passed.20

The Ronin weren’t only recognized for their loyalty, but were seen as heroes. Over the years, it had become tradition to perform the incident using puppets and the Kabuki stage, on the exact date Kira’s mansion was attacked. Hundreds of films, television shows, and textbooks of martial virtues were made of the tale of the 47 Ronins.21 On January 30, many Japanese people go to visit the small memorial museum located in Tokyo. There, people are able to venture off to the tomb of Lord Asano, along with the 47 Ronins, showing their respect as they take in the sights of their tombs and artifacts.

- “Chushingura: Revenge of the 47 Samurai,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, January 1, 2023). ↵

- Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 185. ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- Bitō Masahide and Henry D. Smith, “The Akō Incident, 1701-1703,” Monumenta Nipponica 58, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 153. ↵

- Bitō Masahide and Henry D. Smith, “The Akō Incident, 1701-1703,” Monumenta Nipponica 58, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 151. ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 185. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2018, s.v. “Ronin,” January 1, 2018. ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- “Chushingura: Revenge of the 47 Samurai,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, January 1, 2023). ↵

- Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 186. ↵

- Bitō Masahide and Henry D. Smith, “The Akō Incident, 1701-1703,” Monumenta Nipponica 58, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 154. ↵

- Bitō Masahide and Henry D. Smith, “The Akō Incident, 1701-1703,” Monumenta Nipponica 58, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 160, 162-163. ↵

- Bitō Masahide and Henry D. Smith, “The Akō Incident, 1701-1703,” Monumenta Nipponica 58, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 149. ↵

- Michael McCaskey, “Revenge of the Forty-Seven Ronin,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, July 31, 2021). ↵

- George Sansom, A History of Japan 1615-1867 (The University of British Columbia: Pacific Affairs, 1965), 93. ↵

- Bitō Masahide and Henry D. Smith,“The Akō Incident, 1701-1703,” Monumenta Nipponica 58, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 149. ↵

- Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 186. ↵

12 comments

Maximillian Morise

This is a fascinating tale of honor, loyalty, and death neatly woven by the author into an easily digestible author. I commend you for writing on one of my favorite stories from Japan, and wish you luck in future endeavors. Congratulations on your nomination!

Donald Glasen

Congratulations on your article’s nomination, it most definitely deserved it! I love learning about other countries’ history. It’s amazing to see the differences Between our culture and other cultures. The loyalty that was displayed by the 47 Ronin is extraordinary. The art that was used in the article is amazing.

Jared Sherer

Japanese history and the shoguns are very confusing to me, and this article helps clear them up for me. The idea of honor and the need for seppuku is also a confusing concept, but this article also helps explain this as well. The history of Asano and Kira is very interesting, and this article was well researched and written. The various clans, and the history of the clans and many executions, and ordered seppuku are very interesting and entertaining to learn about. Well done.

D'vaughn Duran

Congratulations on being nominative! This was a great topic to write about. The rich history of Japanese history. Japanese culture is rich with honor and brave aspects of family or themselves. Men and soldiers die or try to die for honor which is an important part. This article is great doing this and it was well structured with the information.

Luke Rodriguez

This was a fantastic read! Also, congrats on the nomination! It was well-deserved. The article was well-written and detailed. This was a well-structured article, and I truly enjoyed reading this. The 47 Ronin showed incredible loyalty, and I found the second-to-last picture you used to be fascinating. These men were ready to sacrifice their lives for a cause they believed was more significant than themselves, an admirable trait that cannot be denied.

Bryon Haynes

This was a beautifully written article on a topic that’s often Americanized and falsely told. Japanese culture as a whole has become so commercialized that it was so invigorating to read something so thoroughly told and researched. It’s rare to find such passion in these, but it was clear this author took her time to deliver something that displayed that. Congratulations.

Isabel Soto

Congratulations on your nomination for Best in Cultural History! I really liked the writing style in this article. I also enjoyed learning about this story and more about Japanese culture. The loyalty that the 47 Ronin had to Lord Asano is remarkable. They waited and planned for two years and knew they would all die after getting their revenge on Kira. i really enjoyed reading your article.

Nnamdi Onwuzurike

Congratulations on your nomination! The Ako incident, which took place in Japan in 1701, was a turning point in the country’s history. The incident involved a group of samurai who sought revenge for the death of their lord, who had been forced to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) after drawing his sword in the presence of a high-ranking official. The incident has been immortalized in Japanese culture and has been the subject of numerous books, plays, and films. The Ako incident is a reminder of the enduring significance of honor, loyalty, and revenge in Japanese culture.

Marissa Rendon

Sydney congratulations on your article proposal! Going into the Japanese history is amazing! Not everyone in America is educated on this type of history. I liked style this article is in, and the images you added into this article. The background behind the images really add on the the article.

Guiliana Devora

This was an amazing article and the author did a great job of telling it. I like the structure and format of this article, it was very easy to follow along and the message was really good. I think it is honorable and brave that the 47 Ronin were ready to die to be able to get their revenge to protect Lord Asano. These were men that were willing to die for something that they believed was greater than them and that is something that no one can take away from them.