—There were 58,000 cases already reported in the year of 1952, and the number quickly escalated. With no cure, no progress, and very little hope, one physician rose to the challenge of ending the Polio epidemic: Jonas Salk. Salk’s first obstacle to ending the outbreak was his need for funding and for lab equipment. After notable development with Salk’s prior research on the flu virus, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine gave the scientist’s ambition a spark of hope, by granting Salk with his own lab equipment. Yet, that spark quickly dimmed as the size of the lab provided, coupled with the restricting rules of the university, deterred Jonas Salk from getting much work accomplished.1 Salk struggled for over a year with limited supplies, until the world grew more desperate for a solution. Public outcry prompted the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to offer Salk the essential lab space, equipment, and researchers needed to investigate the polio epidemic. The increase in cases led to the possibility of more strands of the polio virus being spread across the United States and as such Salk was tasked with identifying the various strands of the virus. Finally provided with the necessary resources, Salk quickly took advantage of this opportunity and expanded the goal of his research to encompass finding a vaccine for polio.

This huge undertaking, to create a solution for polio altogether, came as no surprise to those who knew Salk, as he—referring to the latter years of his medical school career— once famously proclaimed, “…my original ambition, or desire, [was] to be of some help to humankind…in a larger sense than just on a one-to-one basis.”2 Salk’s research extended beyond a mere breakthrough. Ultimately his end “desire” was to end the spread of Polio altogether. This bigger picture mindset can be traced all the way back to Jonas Salk’s early education. He attended college at the early age of fifteen years, and Salk quickly became set apart from other students. He found himself so removed from normality that he was later documented as “a perfectionist” who “read everything he could lay his hands on” from one of the students that grew up with him.3 Salk grew up in a time where death was largely considered a regularity, as husbands, fathers, and sons returned from the savageries of World War I barely recognizable. As Salk continued his educational career, death rates, too, continued to grow as the influenza epidemic began its uproar in 1919, which was soon amplified by polio. Knowing this, it is easy to understand why an individual with Salk’s potential would seek out a field to use his intellectual talents to help humankind. Interestingly enough, Salk originally pursed a medical degree because his parents commonly urged the necessity of financial stability, which they believed was little more than an absolute requirement to live happily in a time of such chaos; and the medical field was an avenue to a stable paying career. Yet, Salk’s passion for research remained at his forefront, and, when presented with the opportunity to do research in biochemistry, he quickly took advantage of it. It is here where Salk was eventually presented with a fellowship at the University of Michigan, where, alongside Thomas Francis Jr—his mentor at the time—he would study flu viruses and later be given the opportunity to discover the polio vaccine.

When Salk received the opportunity to do research in Biochemistry, his career plans began to unfold. His high ambitions were quickly met with an equal challenge in research needed to defeat this disease altogether. Polio, by the year 1950, had reached 20,000 cases a year, and the number had escalated to 58,000 cases in the year of 1952 for the United States alone.4 The exponential growth of polio propagated a rush to find a vaccine and resulted in widespread panic across the entire globe. In an interesting perspective, Sarah Colt—a famous director of the time—explains that in a time of racial segregation, the color-blindness of the disease catalyzed even more fear across America.5 In a desperate attempt to quell the rising cases of Polio, hospitals began using devices such as the Iron Lung much more frequently. Despite common belief, the Iron Lung had previously been implemented prior to the polio epidemic and equivocated with the treatment of a polio patient. The way the machine works is by using a negative pressure gradient in a patient’s chest cavity as compared to the atmospheric pressure. The lungs then naturally receive airflow and begin to fill. Pressure is then added, causing the diaphragm to expand, expelling the air within the lungs. This device became necessary for most patients suffering from polio because the diaphragm would become paralyzed, thus leaving the patient without a way of breathing. These huge devices were very impractical because of their size, but were still widespread, reflecting the desperation everyone felt.

Desperate for progress, a few scientists neglected the appropriate procedures of the scientific method. The most famous case is that of scientist John Kolmer. John Kolmer, best known for the Carl Coolidge Jr. incident, created a vaccine that used grounded monkey spinal cords infected with polio. Kolmer would go on to use this “vaccine of sorts,” to inject more than ten thousand children in thirty-six states. Yet, Kolmer neglected to establish a control for his experiment (children not injected with the disease) and thus was left with no way to determine whether or not the vaccine actually worked. To make matters worse, several children actually developed polio soon after they received Kolmer’s vaccine. Kolmer was subsequently discredited for his work and was shunned within the scientific community. In the end, numerous children were paralyzed and even killed.6

Given a huge degree of responsibility, Jonas Salk understood the effects his work could make on a macroscopic scale. Salk dedicated his life to correctly formulating a method to end polio. As such, the funds from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis were used to assemble a research team to discover the vaccine. Seven years after first beginning his research, the ambition of the young medical student had finally reached the fulcrum. Dr. Jonas Salk, confident in the safety of his vaccine, began testing it in trials. Documented as “the most elaborate program of its kind in history” by historian William L. O’Neill in his book American High: The Years of Confidence, Salk’s trial involved over twenty thousand physicians and public health officials, and over two hundred and twenty thousand volunteers.7 At the height of its popularity, more than one million children between the ages of six and nine took part in the trial, and the monumental field experiment was backed not only by great confidence in the years of research Salk used to create the vaccine, but by the extent to which Salk confided in his research. Salk dedicated his entire life to discovering this vaccine, at one point going so far as to divorce his wife, claiming later that “I like to think to marry science.”8

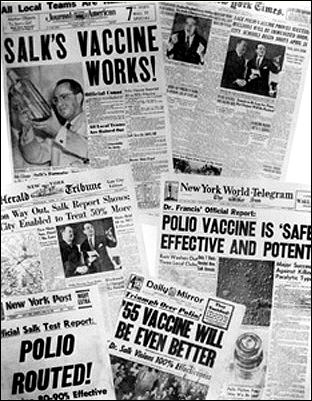

On April 12, 1955, Salk released the final results of the field trials. Salk’s vaccine was 90% effective to PV1, PV2, and PV3.9 Additionally, bulbar polio effectiveness was at a 94%. This undoubted success was as monumental as it was unprecedented, and news of the vaccine was heard around the world. Places from Denmark to Australia alike all rushed to obtain vaccines. The surreal success of Jonas Salk’s research earned him the praise of people across the globe, who hailed Salk as a hero. In response to the world’s reaction, popular television host Edward Murrow told Salk, “Young man, a great tragedy has befallen you—you’ve lost your anonymity.”10 And Murrow was right. Jonas Salk did his best to avoid the praise and instead divert the spotlight to campaign for mandatory vaccines. Salk believed that what he had accomplished was an obligation to humanity; a job that would have had to be completed by anyone had they been in his shoes. Nonetheless, Jonas Salk took full advantage of the opportunity his newly found fame had provided to advocate for the vaccine on a grand scale. This advocacy eventually developed into the March of Dimes. While Dr. Salk never truly believed what he had accomplished should be praised, as we look back at the epidemic as a whole, it is easy to understand the potential catastrophe that was avoided had the vaccine not been developed. Thanks to his work, the annual number of polio cases within the United States dropped to only 161 by the year 1961.11

Salk’s success was brought about by the relentless persistence brought about by a dream held by his younger self. Dr. Salk understood this and sought to create an institution that provided an avenue for scientists to focus on their research and not the resources required for the labs. With the help of many supporters, but particularly the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, Salk was able to see his ultimate dream come true. In an interview about the future of the institute, Salk said, “In the end, what may have more significance is my creation of the institute and what will come out of it, because of its example as a place for excellence, a creative environment for creative minds.”12 Through the institute, Dr. Salk had hope that the diseases that seem impossible to cure today, will become another disease of the past; while polio’s effect left a large scar across the world, Dr. Salk’s vaccine paved the foundation for immunology as a whole.

- John Bankston, Jonas Salk and the Polio Vaccine (Bear, Delaware: Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2002), 30-32. ↵

- “Jonas Salk, M.D.: Developer of the Polio Vaccine,” Academy of Achievement (website), last modified November 27, 2018, https://www.achievement.org/achiever/jonas-salk-m-d/#interview. ↵

- Debbie Bookchin and Jim Schumacher, The Virus and the Vaccine (St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2013), 22. ↵

- Debbie Bookchin and Jim Schumacher, The Virus and the Vaccine (St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2013), 22. ↵

- Robert LLoyd, “A fearful disease and how it was stopped,” LA Times (website), February 2, 2009, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2009-feb-02-et-polio2-story.html. ↵

- Paul Offit, The Cutter Incident: How America’s First Polio Vaccine Led to the Growing Vaccine Crisis (New York: Yale University Press, 2007), 56. ↵

- William O’Neill, American High: The Years of Confidence, 1945-1960 (United States: Free Press, 1989), 137. ↵

- World of Microbiology and Immunology, 2019, s.v. “Salk, Jonas (1914- 1995).” ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016, s.v. “Monovalent Oral Poliovirus Vaccine.” ↵

- Grace Glueck, “Salk Studies Man’s Future; Salk Studies Man’s Future Renewed Interest in His Idea,” New York Times, April 8, 1980. ↵

- World of Microbiology and Immunology, 2019, s.v. “Salk, Jonas (1914- 1995).” ↵

- “Jonas Salk, M.D.: Developer of the Polio Vaccine,” Academy of Achievement (website), last modified November 27, 2018, https://www.achievement.org/achiever/jonas-salk-m-d/#interview. ↵

31 comments

Cristianna Tovar

Congratulations on your nomination, Jeremiah! Your article did a great job of telling the struggles and ultimate success of Jonas Salk, which is very inspiring. Without his determination and persistence, there could have been a lot more people who were reported to have polio, which was a potentially deadly disease. This was a very informative article, good luck at the awards ceremony!

Sebastian Azcui

Great article! You did a great job explaining Polio and how it was discovered. The afticle talked how it can easily be transmitted and how it can spread, making it a big concern as a lot of people can get it. A lot of people got the disease and many of them even died as there was no cure for it. Salk made a great job finding the cure for Polio as it was required and extremely needed because a lot of people were dying and Polio kept spreading.

Pablo Ruiz

What an informative article. Polio was a disease that was claiming live after live in the 1900s. I find it fascinating that Salk made finding a cure for this disease his focus and was successful. He faced a lot of adversity to even get started in his research but nonetheless was able to overcome it change the world. In addition it is noble of him to start an institution to aid other scientist in their research.

Trinity Casillas

I can’t imagine being one of the kids or the parent of one of the kids who got polio from Kolmer’s “vaccine” that just sounds like a nightmare. It’s also crazy to think Salk divorced his wife to find the vaccine but I think it just shows his determination and dedication. I admire Salk so much for not basking in his new fame but instead used it to advocate for widespread vaccines.

Breanna Perry

This article was a very interesting and informative read. I like how this article gave a good bit of personal information on Salk and how important he was with his discoveries for the Polio disease, as well as explaining the prevalence of the disease. I hadn’t known much about this topic, so I’m glad I got to read this article.

Pablo Medina

This article was very interesting and informative about Polio and how much of an issue that disease truly is. I didn’t know much about Salk and the work done towards helping deal with Polio. I think this article did a good job at not just going over the disease and how it was very contagious and how many people were affected by it, but at highlighting the positive work done by Salk.

Luis Arroyos

Your article is actually very captivating, Jonas Salk’s discoveries are amazing. In our society, we do not think about the origins of some of these discoveries and how important they were. They really pave the way for all future research on top of saving many lives. I really learned something new, great article!

Amanda Quiroz

I can only imagine how much weight was on Salk’s shoulders because of pressure to find a cure for such a contagious disease. Polio spread far across the country and it must have taken him a lot of strength in order to discover a cure. I admire his ambitions to help others. He saved so many lives from his discovery.

Jose Maria Llano Aranalde

Really interesting and informative article. I liked how Salk felt pressured to find a cure for polio but was not scared. He was up for the challenge. He was passionate about the things that he was doing. I think that his other passion for helping people also allowed him to stay focused and driven.

Cassandra Sanchez

I can only imagine how much pressure Salk faced in trying to find the cure that was so desperately needed. He has helped save so many lives and improve the lives of many others. I thought it was interesting how Salk had a sort of calling to help others through his work and he finally got the best opportunity to do so. Even after finding the cure, his foundation continues to help others which is very inspiring.