March 22, 1622 marks the day Natives said “enough” to the colonization of Jamestown. After the Natives killed 347 settlers in protest, the English claimed the attack was unprovoked. However, the Natives point to two reasons for their attack: the colonial encroachment of their land, and the kidnapping of Pocahontas. This day also symbolizes the end of the Native character, as far as the English were concerned. Indigenous tribes would subsequently be painted by Europeans as: “errors of nature,” “garbage,” “false-hearted people,” “know not God, nor faith,” “dregs,” “Spawne of Earth,”1 but most commonly as “Savages.”2

In late 1606, the London Company, which was a joint-stock company under King James I, sent out three ships to establish a trading post in Virginia. Under the command of Christopher Newport, 144 settlers embarked on a voyage to the New World. The settlers hoped to gain large profits by trading with American Natives, discovering precious metals, and producing goods to trade with England. After the long voyage, only 100 settlers and four boys survived and set up a small trading post named Jamestown on a low-lying peninsula in May of 1607. The colonists began to quickly realize that the location of their settlement was not ideal. While the new colony was positioned well for military defense, as it was surrounded by water on three sides, the location itself was a murky swamp. Additionally, colonists were unwilling or unable to work in the fields, which left them unable to grow their own food. This meant that they would rely heavily and almost completely on Natives to provide supplies. After realizing some of the issues plaguing the colony, Captain Newport left Jamestown to retrieve supplies and more colonists from England. Soon after he left, disease and illness began to take over the colony, and when he returned in January 1608, only 38 of the original 100 colonists were alive.3

In the winter of 1608, John Smith assumed control and the colony survived the winter. Smith was familiar with Jamestown and about a year before taking command, he had been captured by the Powhatan tribe. Smith believed that when he was captured, he was condemned to death by the Powhatan Chief. He claimed that he was saved by the intervention of Pocahontas, the most beloved daughter of the Chief. Smith was right in the fact that the Tribe did plan on killing him, but many believe that it was for the purpose of a Native spiritual ceremony. The ceremony would involve killing Smith but for the sole purpose of having him be reborn as a member within their tribe. Nonetheless, after this event and Pocahontas’s intervention, Smith strengthened his relations with the Powhatan tribe. The kidnapping of John Smith shows how much the Natives approved of him. They were so fond of Smith that the tribe helped get crucial supplies, especially corn, to the settlers for the harsh winter, and due to their aid, only seven men died in the winter of 1608.4

As the colony progressed, the London Company started to grow weary of the lack of profits coming from Jamestown. The new colony in Virginia was not producing the wealth they had hoped. The biggest issues that the colonists faced were the Natives not willing to help work, not trading very valuable items, and there seemed to be no potential mineral wealth. The company decided rather than abandoning the colony, they would change their strategy and send over more settlers. They incentivized individuals by offering 100 acres of land in Virginia to be gained after seven years of work for the company. In June of 1609, 500 settlers (400 men and 100 women) embarked on a voyage from England to Virginia. When they arrived, only 400 settlers survived the journey. Once again, the new colonists made the same mistake and failed to plant subsistence crops. However, this time the Natives were not as eager to help them, as their beloved John Smith was no longer at the colony. Smith had gotten wounded in a gunpowder explosion earlier in the year and returned to England. Without the Native’s help, illness, disease, and starvation once again plagued the colony. By the end of the winter, only about sixty colonists were still alive.5

Those who did survive the winter decided to abandon the settlement. But, while on their journey back to England, they happened to cross paths with a ship sailing to the colony. The ship held more settlers and supplies, and the colonists who were attempting to abandon the colony decided to return and give it another chance. The London Company then imposed strict guidelines to prevent further starvation of the colonists, but the Company was still not making a profit. The company continued to incentivize the colonization of Jamestown by offering land to those who moved to Jamestown and to those who would help others become settlers. After sending countless waves of resupplies and refusing the give up on Jamestown, the Company ended up sending approximately 4,500 settlers to Virginia.6

In the past, the first attempt by the British crown to establish a permanent colony in North America was in the late sixteenth century. Queen Elizabeth and Sir Walter Raleigh, her advisor, wanted to create a settlement in order to keep the existing Spanish outposts under control. They initially established the Roanoke colony in 1587 to be the first permanent colony. Three years later when a resupply ship landed, they found the colony abandoned. The next attempt to create a colony was Jamestown, under King James I, in 1606. The primary difference between Jamestown and Roanoke was the purpose of each settlement. Jamestown was going to be established for potential economic gains whereas Roanoke was used to check English rivals. King James I understood that this colony would be an investment that might take a long time to become profitable.7

In order to ensure that Jamestown would produce a profit, the colonists had to come up with an export that people in England could not produce themselves. Due to the emphasis on the commercial outputs of Jamestown, the Virginia Company of London came into existence in 1606. This company would be composed of investors and Sir Thomas Smythe.8 These investors put money into the company to establish Jamestown on the understanding that they would be making a profit.9 The company was granted a charter that would allow them to establish a colony of one-hundred-mile proximity between Long Island and Cape Cod.10 Due to the huge investments made in the colony of Jamestown, the Company was not willing to abandon the settlement. Additionally, because King James I viewed Jamestown as a long-term investment, the lack of profit was interpreted merely as a “rough start” to the potentially prosperous future.

Things finally began to turn around in Jamestown when a man named John Rolfe began experimenting with tobacco seeds he obtained from the West Indies. This specific seed of tobacco was different from the native plant they saw in Virginia. This new form of tobacco was sweet and mild rather than the harsh and bitter native plant, and he believed they could sell this product to England. The intention of Jamestown was to seek profit and with the discovery of this cash crop, colonists and investors began to see a return on their capital. Rolfe sent four barrels of the crop to England in 1614. Shortly after, in 1616, tobacco exports increased to 2,300 pounds. Then, in 1617, they grew again to 18,839 pounds, then it doubled in 1618 to 49,528 pounds. The tobacco trade was taking off, but tobacco had its opposition. King James I did not approve of smoking, but tobacco had become extremely popular and a prominent good in society. The king disapproved of smoking so greatly that he published a piece called “A Counterblaste to Tobacco,” where he called tobacco “dangerous to the lungs.” But, during this era, the harms of smoking were unknown and King James I was trying to combat something that was already well-established in society. Even the King, regardless of his personal beliefs, could not ignore the great economic benefits tobacco was providing the country.11

While the production of tobacco was beneficial economically, the growth of the tobacco industry posed problems to those settlers in Virginia. When the colonists realized the potential profit they could obtain by selling tobacco, they began solely producing the crop. Due to the single focus on tobacco, the vast majority of colonists once again failed to plant crops that could be used as food. This prompted the Company to attempt to discourage the production of tobacco, but that failed. The tobacco madness that motivated the colonists caused the desire to create larger and more tobacco plantations. Settlements began to expand past the original Jamestown area, and the banks of rivers became a hot spot for farmers to expand their plantations.12 This did not sit well with the Natives, as the expansion of Jamestown settlers once again encroached on their land. Furthermore, the Company’s promise of providing 50 to 100 acres of land after seven years of work now started to be redeemed to make larger tobacco farms. This continued impediment on Native lands began to cause frustration and tension directed at the settlers.

In 1613, a voyage around the Chesapeake Bay led by Captain Samuel Argall took place. They were able to land in what is now known as Washington DC, where Argall’s men received intelligence that the beloved daughter of Chief Powhatan, Pocahontas, was in the area visiting a Patawomeck village. She had not been seen in three years and seemed to have disappeared as the expansion of Jamestown continued. In addition to “hiding” Pocahontas, the Powhatan tribe began kidnapping settlers and stealing tools from the town. But with the intel of her location, Argall got the idea that would return the kidnapped and stolen items. Argall wrote: “I presently repaired, resolving to possess myself of her by any stratagem that I could use for the ransoming of so many Englishmen as were prisoners with Powhatan, as also to get such arms and tools as he and other Indians had got by murther and stealing from others of our nation, with some quantity of corn for the colony’s relief.” The plan to kidnap Pocahontas was set in motion. Argall and his men hoped that with Pocahontas in their possession they could use her to retrieve the stolen tools and kidnapped men.13

Captain Argall set up a deal with the Patawomecks to set up the capture of Pocahontas in assurance that no harm would come to the village. A native man named Iopassus, who was the local native weroance, and his wife became co-conspirators with Argall. As word of the English ship nearby made its way to the tribe and Pocahontas, she became curious and wanted to see the ship for herself. Iopassus and his wife accompanied her to the river where the wife asked Pocahontas if she would accompany her on the ship. Reluctantly, Pocahontas said no. But after the wife busted out into tears, and Iopassus refused to let his wife board alone, Pocahontas said yes to going aboard. Once aboard, they were shown around the ship and told to stay the night. The next morning, Argall let Iopassus and his wife return to shore but refused to let Pocahontas go until the Powhatans agreed to release the eight Englishmen that the Powhatans were holding captive along with their stolen weapons. Ralph Hamor, a man aboard the ship, recalls Pocahontas being terribly upset and discontented, but Argall assured her that she would be treated as an honored guest. He even suggested that she could be used as a peace negotiator between the English and the Powhatans. On April 13, 1613, Argall made his way back to Jamestown with his new prized possession and sent word to Chief Powhatan that his cherished daughter was captured.14

Thomas Dale had become the new man in charge of Jamestown and he very quickly began indoctrinating Pocahontas into the Christian faith. He put her faith under the oversight of Reverend Alexander Whitaker, who was the most responsible for Pocahontas’s conversion to the Christian faith. Dale met with Pocahontas on several occasions shortly after her capture and taught her about the English way of life and the English language. But most importantly, shortly after her capture, Pocahontas struck up a new friendship with a recently widowed John Rolfe, the man who had introduced tobacco to the colony.15

Several months after the kidnapping of Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan attempted to gain his daughter’s freedom back. He freed the seven Englishmen whom the tribe had held captive, and guided them back to Jamestown. The Chief also promised that if Pocahontas was returned, he would give back the weapons and also send 500 bushels of corn for the colony. Thomas Gates replied on behalf of the English that Pocahontas would not be released until all of their demands were met and the weapons were returned. Silence then came from the Powhatan people. After a year of being held hostage, Dale began to grow frustrated. He decided to confront the Natives about why their demands had not been met. Dale took over 300 armed Englishmen and sailed up to Werowocomoco, which is the former Powhatan capital. After a day or two, the Natives asked what the English were up to. Dale replied that he was ready to release Pocahontas, who was aboard, if Chief Powhatan was ready to meet all their demands. Unknown to Dale, Chief Powhatan was not in Werowocomoco, as he had left a couple of months earlier. The Chief’s half-brother, Opechancanough, was left in charge and he could negotiate with the English. But Dale refused to negotiate or talk to anyone who was not Chief Powhatan.16

A series of short attacks involving Natives and Englishmen took place and resulted in some Native casualties. In an attempt to foster peace and afraid of more violence, Pocahontas decided to go ashore to talk to her people. According to Dale, she talked with the Natives and told those who officially represented the tribe that “If her father had loved her, he would not value her less than old swords [artillery] pieces, or axes; wherefore she would still dwell with the Englishmen, who loved her.” It should be noted that Pocahontas had fallen in love with John Rolfe by this point. But after the message made its way to the Chief, he sent a message to Dale where he assured the delivery of the weapons within fifteen days, along with corn. The chief also specifically reassured Gale that all Natives who were under him were to “be included and have the benefit of the peace.” The chief also said that he now considered Pocahontas to be Dales’s “child” and that she would “ever dwell with him” and the Englishmen. Chief Powhatan declared himself and Dale “ever friends,” and now Pocahontas would be the shared “peace child” between the English and Natives. As Chief Powhatan said, Chief Opechancanough also complied with the agreed terms and he too reluctantly declared his “love” for Dale. In reality, Chief Opechancanough did not have much choice in making this declaration but the negotiations came to an end. Dale wrote back to Jamestown saying: “every eight or ten days I have messages and presents from [chief Powhatan], with many appearances that he much desire to continue friendship.” Unbeknownst to Gale, Opechancanough was patiently waiting for his opportunity for revenge.17

After being kidnapped in early 1613, a little over a year later Pocahontas had undergone three significant changes: the first was her conversion to Christianity; then her permanent residing with the English; and lastly her marriage to John Rolfe on April 5, 1614.18

After Powhatan’s death, his successor Chief Opechancanough came to power. Naively, the English believed there was finally a time of peace in Virginia and its colony Jamestown; but the view of Natives and their treatment remained the same. The primary policy of the English was the transformation of the Native society, or as William Strachey said, “we shall by degrees change their barbarous natures, make them ashamed . . . of their savadge nakednes, informe them of the true god, and of the waie to their salvation, and fynally teach them obedience to the kings Majestie and to his Governours in those parts.” From 1613 to 1622, relations were peaceful on the surface, but tensions stirred just below that surface. The desire for more land for tobacco continued to threaten the neighboring tribes around Jamestown. By 1620, most Natives between the James and York rivers faced two options: either concede to the settlers’ demands by giving up their land and face their social and religious transformation, or rid themselves of the Englishmen.19

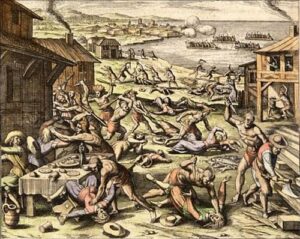

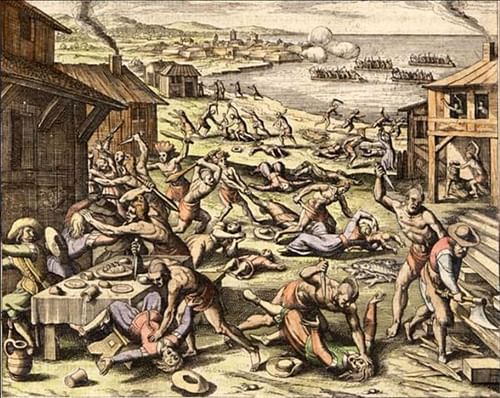

On the morning of March 22, 1622, Natives who were allied with the Powhatan tribe arrived around numerous Jamestown plantations seeking to trade. However, in an instant, these seemingly peaceful approaches vanished. The Natives grabbed weapons and tools that were around and began to kill the settlers.20 They drew knives hidden in their garments and began brutally attacking every man, woman, and child within their reach. Friendship offered no protection. The attack took place at many plantations on the outskirts and almost everyone perished. As the list of victims was reported, there were 17 dead at College Lands, 27 dead at Captain Berkeley’s Plantation, 75 or more dead at Martins Hundred–which was seven miles from Jamestown–and many others throughout the colony itself. Many among the dead were prominent residents and council members. A few of the communities received a warning from a Christian Native and were able to survive the attack. By the end of the day, the death count was 347 people, which was more than one-fourth of the colony’s population. The tragedy did not end there. For weeks to follow, Natives would continue to pick off settlers and travelers. Argall reported, “Since the massacre, they have killed us in our own doors, fields, and houses.”21

The massacre was one of the first colonial events to receive widespread attention in England. When news reached Europe during the first week of July, people were fascinated by the heinous acts of the Natives and the heroism of the colonists. A prominent member within the Virginia Company shared, “The fame of our late unhappy accident in Virginia, hath spread it selfe… into all parts abroad… it is talked of all men.” This interest in the event and desire for official accounts brought forth two publications. The first was the official account brought by the Viriginia Company titled: A declaration of the State of the Colony and Affaires in Virginia. With a Relation of the Barbarous Massacre in the time of peace and League, treacherously executed by the Native Infidels upon the English, the 22 of March last. The publication was written by Edward Waterhouse and published in August of 1622. The goal was to make known to the public that “it was not the strength of a professed enemy that brought this slaughter on them, but contrived by the perfidious treachery of a false-hearted people, that know not God nor faith.” In other words, this vicious act was unprovoked and was due to the Natives’ inherent flaws.22 He created an emotional and gory commentary that denounced the Powhatan Confederacy. Waterford strongly asserted that the only way to restructure the relationship between “Anglo-Natives” was with the complete eradication of the Native people.23

The second publication was a work of poetry titled: A Poem on the Late Massacre in Virginia. With particular mention of those men of note that suffered in that disaster. The poem was written by Christopher Brooke and published in the summer of 1622. The poem describes the Natives as:

“For, but consider what those Creatures are,

(I cannot call them men) no character

Of God in them: Soules drown’d in Good;

Errors of Nature, of inhumane Birth,

The very dregs, garbage, and spawne of Earth” 24

The initial response from King James was to employ the military. He donated ammunition and arms that were no longer in service, and the London Company also began gathering weapons. John Smith even offered to return to Virginia to “inforce the Salvages to leave their Country, or to bring them in[to] feare and subjection.” While the company did not send him, their ideas were the same. The savages needed to be destroyed. In the next decade, the colony showed no mercy. Prior to the massacre, the colony and its settlers had distinguished friendly and non-friendly tribes; now all Natives were simply enemies. Masses of settlers embarked on journeys to destroy every instance of savage presence in the area between the James and York rivers. In January of 1623, the Virginia Council of State said “by Computatione and Confessione of the Indyans themselves we have slayne more of them this yeere, then hath been slayne before since the begininge of the Colonie.” The Governor at the time saw the task as simply the “extirpating of the Salvages.”25 Nonetheless, the Virginia Massacre of 1622 symbolizes an end to the differentiation between friendly and nonfriendly tribes. It serves as a turning point in the way Natives were perceived by the English and marks the downfall of their reputation. After this event, they were no longer Natives; they were savages.

- Christopher Brooke, “A Poem on the Late Massacre in Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 72, no. 3 (July 1, 1964): 262. ↵

- Alden T. Vaughan, “‘Expulsion of the Salvages’: English Policy and the Virginia Massacre of 1622,” The William and Mary Quarterly 35, no. 1 (January 1978): 76-77, https://doi.org/10.2307/1922571. ↵

- Milton Berman, “Jamestown.,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Milton Berman, “Jamestown.,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Milton Berman, “Jamestown,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Milton Berman, “Jamestown,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Milton Berman, “Jamestown,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Stephen Slivinski, “The Lessons of Jamestown,” Region Focus, June 1, 2010, 27–29. ↵

- Victor Reklaitis, “Jamestown’s John Rolfe Grew Peace, Prosperity Lift: His Tobacco Helped Smooth Colonial Life in Virginia,” Investor’s Business Daily, July 19, 2011. ↵

- Stephen Slivinski, “The Lessons of Jamestown,” Region Focus, June 1, 2010, 27–29. ↵

- Victor Reklaitis, “Jamestown’s John Rolfe Grew Peace, Prosperity Lift: His Tobacco Helped Smooth Colonial Life in Virginia,” Investor’s Business Daily, July 19, 2011. ↵

- Victor Reklaitis, “Jamestown’s John Rolfe Grew Peace, Prosperity Lift: His Tobacco Helped Smooth Colonial Life in Virginia,” Investor’s Business Daily, July 19, 2011. ↵

- Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth, 1st ed. (The Lutterworth Press, 2015), 72-73, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ↵

- Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth, 1st ed. (The Lutterworth Press, 2015), 74-75, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ↵

- Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth, 1st ed. (The Lutterworth Press, 2015), 78-79, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ↵

- Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth, 1st ed. (The Lutterworth Press, 2015), 81-82, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ↵

- Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth, 1st ed. (The Lutterworth Press, 2015), 82-83, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ↵

- Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth, 1st ed. (The Lutterworth Press, 2015), 84, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ↵

- Alden T. Vaughan, “‘Expulsion of the Salvages’: English Policy and the Virginia Massacre of 1622,” The William and Mary Quarterly 35, no. 1 (January 1978): 72-73, https://doi.org/10.2307/1922571. ↵

- Nicholas K. Mohlmann, “Making a Massacre: The 1622 Virginia ‘Massacre,’ Violence, and the Virginia Company of London’s Corporate Speech,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 19, no. 3 (2021): 419–20, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2021.0014. ↵

- Alden T. Vaughan, “‘Expulsion of the Salvages’: English Policy and the Virginia Massacre of 1622,” The William and Mary Quarterly 35, no. 1 (January 1978): 76, https://doi.org/10.2307/1922571. ↵

- Christopher Brooke, “A Poem on the Late Massacre in Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 72, no. 3 (July 1, 1964): 259–61. ↵

- Nicholas K. Mohlmann, “Making a Massacre: The 1622 Virginia ‘Massacre,’ Violence, and the Virginia Company of London’s Corporate Speech,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 19, no. 3 (2021): 420–21, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2021.0014. ↵

- Christopher Brooke, “A Poem on the Late Massacre in Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 72, no. 3 (July 1, 1964): 262 ↵

- Alden T. Vaughan, “‘Expulsion of the Salvages’: English Policy and the Virginia Massacre of 1622,” The William and Mary Quarterly 35, no. 1 (January 1978): 76-77, https://doi.org/10.2307/1922571. ↵

4 comments

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

Well written account of the turning point in which the English settler’s shifted their views of native Americans. Very well documented and backed with plenty of sources!

Quinten Mero

Great job Sierra! While the tale of the Jamestown colony is well-known to most Americans, your article has provided me with a new depth of knowledge on the subject. I was interested to learn from your article that an influential figure such as King James I was against the use of tobacco and cited fears of risk to health. Overall, your article is well-crafted and full of information. Great work!

Vianna Villarreal

Very interesting! I really enjoyed your article, I think emphasizing on these past oppressions that occurred over our countries history is very important to share. Definitely with native Americans after seeing so many stories about how they were supposedly treated and the harsh reality of what they endured.

lramirez46

This is a wonderfully written article. You do a good job of introducing how colonists arrived, established a colony, and the way the first connections to the Native Americans. You also do a good job of describing the way the colonist deteriated their relationships with the Natives even though they had saved the colonists in the early years of their settlement.