In 1982, the song “Valley Girl” was released by father-daughter duo Frank and Moon Zappa, in which it depicts the dialect that is spoken in the San Fernando Valley (Zappa & Zappa, 1982). This song led to the rise of what is now known as the “Valley accent,” one of the most recognized linguistic stereotypes in the United States, and a cultural outbreak of people beginning to use a new dialect, which included phrases such as “awesome,” “fresh,” “no duh,” “take a chill pill,” and “I’m so sure” (A. Suarez, personal communication, April 13, 2021).

Yet, this did not just have a cultural impact in the United States, but it also began to surge in Mexican culture, beginning the rise of what is known as a fresa (Spanish for “strawberry”), a social slang term used to describe what can be considered a Mexican valley girl. Although fresas show different lexical features, such as o sea, cool, súper, and qué oso (“like/I mean,” “cool,” “super,” and “what a bear” (cultural meaning: “how embarrassing”)), fresas and Valley Girls are more similar than what we might think when it comes to their way of speech.

A Valley Girl is typically described being from North America, specifically California, and they are recognized for their way of speech. Although the common way to describe this way of speech is known as “Valley Girl” talk, there is a more formal way of describing it, known as “uptalk.” Uptalk, sometimes also called a high rising terminal (HRT), is the use of “high-rise” or a manner of speaking in which declarative sentences are uttered with a rising intonation at the end, as if they were questions (Habasque, 2020).

California vowel shift, or CVS, is another feature of Valley Girl speech. For example, when speakers of this dialect say the word cool, they front the o sound of cool. (Habasque, 2020; Podesva, 2011). Another aspect of the CVS is that speakers tend to back or raise the front vowel /æ/. For example, in ban and other words in which /æ/ is followed by a nasal consonant, the speaker raises the vowel, pronouncing it higher in the mouth by raising her tongue. Moreover, in bat and other words /æ/ is followed by any other consonant, it is pronounced farther back of the mouth while lowering the tongue (Podesva, 2011).

The Valley Girl accent has been stereotypically associated with young women, often described as “sorority girl speech” or “Valley Girl speech,” triggering images of “rich, white young females from San Fernando Valley” of California who may be seen as “ditzy” (Tyler, 2015, p. 286). Moreover, Valley Girl speech, or more specifically the California vowel shift, carries the social meanings of carefreeness, whiteness, femininity, and privilege (Podesva, 2011; Villarreal, 2018, p. 52).

So, what does Valley Girl speech have to do with how fresas talk? In this case, the fresa accent originates from the Valley Girl accent, when young Mexican women who went to American schools began to adapt to the accent. We begin to see the beginning of the fresa accent represented in the novel Las niñas bien “The nice girls” by Guadalupe Loaeza (Martínez Gómez, 2018).

A fresa is one of the modern stereotypes in Mexican society and is used as a term to refer to a person, usually a teenager or a young adult, who fits into the stereotype of someone who has an expensive lifestyle, behaves pretentiously, and who speaks Mexican Spanish very distinctively (Holguin Mendoza, 2017; Martínez Gómez, 2014). In Mexican society, being called a fresa can also be seen and interpreted as a back-handed compliment, being associated with a stigma and teasing. This also “projects a particular social refinement rooted not only in traditional Mexican categories of class, race, and gender, but also in white, upper-middle class culture, as well as consumer and leisure patterns extracted from the U.S. cultural landscape of late capitalism” (Holguín Mendoza, 2017, p. 6).

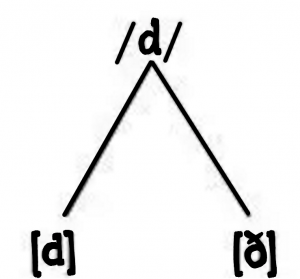

In fresas’ form of speech, they tend to lengthen their vowels more than necessary, especially at the end of each phrase (ex. fraseeeeeee; “phraaaaaaase”). They also tend to put an emphasis on and lengthen the letters “s” and the “c” in “ce” and “ci.” For instance, in the sentence neta güey el cielo está súper celeste (“like dude, the sky is super light blue”), we would hear this lengthening in the /s/ sound at the beginning of the words cielo and celeste (A. Suarez, personal communication, April 13, 2021). When producing consonants such as “b,” “d,” or “g,” the movement can described as a “‘hot potato in the mouth’ with a lack of closure of the mouth (like when one eats something hot)” (Martínez Gómez, 2014, p. 89-90), leading to the reduction or the loss of these sounds.

Another phonetic feature in fresa speech is the use of glottal stops, a type of consonantal sound produced by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract, or more precisely, the glottis (Martínez Gómez, 2014). For example the word o sea (“I mean”) inserts a glottal stop at the beginning of the phrase. Fresa speech also includes creaky voice, which occurs when speakers lower their pitch and produce irregular vibrations of their vocal folds, failing to push enough breath through them (Anderson et al., 2014; Van Edwards, n.d.). Creaky voice may be heard in phrases such as qué oso (literal translation: “what a bear,” cultural meaning: “how embarrassing”) (Martínez Gómez, 2014).

In fresa speech, it is also known that they employ a rising intonation, or uptalk. An example would be “o sea güey, ¿vamos al cine? (translation: like dude, we’re going to the movies?), in which we hear the rising intonation, as if it were a question, rather than a statement (Martínez Gómez, 2014). Fresas also tend to phonologically reduce certain words in their lexicon, such as güey –> wei –> [we] (“dude”) or o sea –> osea –> [sa] (“I mean”). Fresa lexicon also shows the frequent uses of certain phrases such as no manches güey (“come on dude”) and tipo de que (“be like”) (Martínez Gómez, 2014).

Furthermore, “fresas are not only perceived as being influenced by American culture in the type of life that they have but also in their language style” (Martínez Gómez, 2014, p. 94). What is interesting to see is that one of the few differences between Valley Girl speech and fresa speech is that the fresa dialect is perceived as using “proper” vocabulary by avoiding “Mexican slang.” However, fresa speech is also considered improper because of its constant use of English, in that it mixes in Spanglish, or words and idioms that come from both Spanish and English. Some of the English words and expressions that fresas tend to incorporate into their Spanish include words such as qué cool and súper (Martínez-Gómez 2014).

Both Valley Girls and fresas are seen to have similar speech forms as both groups tend to over-enunciate vowel forms, and they demonstrate uptalk in their dialect, speaking as if they were asking a question or in an interrogative way (Habasque, 2020; Martínez Gómez, 2014; Podesva, 2011). Both forms of speech are also perceived to be characteristic of speakers of a higher economic status, in both the United States and in Mexico, such as how a Valley Girl is perceived as being rich, white young females from San Fernando Valley (Tyler, 2015) and fresas being described as upper class young Latinas who lead a lavish lifestyle (Holguin Mendoza, 2017; Martínez Gómez, 2014). Both forms of speech are connected through fresas’ adaptation and use of English words and Valley Girl accents (Martínez Gómez, 2014, 2018). However, what is more interesting is how it all began with just a song written by a father and daughter.

References

Anderson, R. C., Klofstad, C. A., Mayew, W. J., & Venkatachalam, M. (2014). Vocal fry may undermine the success of young women in the labor market. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e97506. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097506

Habasque, P. (2020). Linguistic misogyny as a parodic device: Valspeak markers in Jimmy Fallon’s “Ew!” Anglophoia, 29. https://doi.org/10.4000/anglophonia.3352

Holguín Mendoza, C. (2017). Sociolinguistic capital and fresa identity formations on the U.S.-Mexico border/ Capital sociolingüístico y formaciones de identidad fresa en la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos. Frontera Norte, 30(60), 5-30. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/fn/v30n60/0187-7372-fn-30-60-00005.pdf

Martínez Gómez, R. (2014). Language ideology in Mexico: The case of fresa style in Mexican Spanish. Texas Linguistics Forum, 57, 86-95. http://salsa.ling.utexas.edu/proceedings/2014/Martinez.pdf

Martínez Gómez, R. (2018). Fresa style in Mexico: Sociolinguistic stereotypes and the variability of social meanings [Doctoral dissertation]. The University of New Mexico. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1056&context=ling_etds

Podesva, R. J. (2011). The California vowel shift and gay identity. American Speech, 86(1), 32-51.

Tyler, J. C. (2015). Expanding and mapping the indexical field: Rising pitch, the uptalk stereotype, and perceptual variation. Journal of English Linguistics, 43(4), 284-310.

Van Edwards, V. (n.d.). Vocal fry: What it is and how to get rid of it. Science of People. https://www.scienceofpeople.com/vocal-fry/

Villarreal, D. (2018). The construction of social meaning: A matched-guise investigation of the California vowel shift. Journal of English Linguistics, 46(1), 52-78. doi:10.1177/0075424217753520

Zappa, F., & Zappa, M. (1982). Valley girl. On Ship arriving too late to save a drowning witch. Barking Pumpkin Records

30 comments

Adelina Wueste

This was such an interesting article! The article described the connection between valley girls and fresas in a super understandable manner. Your explanation of how the sounds that Fresas make versus the sounds that Valley girls make when speaking was excellent. You described the different sounds very well with terms such as the glottal stop and uptalk. I really liked how you included examples of fresa and Valley girl speech throughout the article. Your examples and explanations of sounds helped me be able to understand the speech characteristics that valley girls and fresas share.

Rafael Portillo

Hi Ana, this article was very well written and caught my attention the entire time. As a Mexican-American I understand your argument quite well. In our current society stereotypes will always exist and being called a “fresa” is pretty rude. Just because we were raised in a more American lifestyle than latin one doesn’t make it right to be made fun of by the way we speak the same language everyone else speaks.

Melyna Martinez

Hi Ana! This article is so interesting, I would have never thought that there was a fresa equivalent in the US. While the similarities are so astonishing, it is funny to see how the influence of the Mexican version came a bit from the US. As it is true that usually high-class Mexican girls do have the opportunity to learn English/ come to the US for school, which is where the mixing of both English and Spanish happens. Which I think is a very interesting way Hispanic show they are high class with their knowledge of English.

Natalia Ramirez

Hi! Thank you for this great article! Your article caught my attention, especially because I’ve been told many times I sound like a “Valley Girl”, and other times I’m told I sound like a “fresa”. I’ve never really known what people mean by this, but you’ve definitely helped me understand what people are talking about now, which is pretty funny.

Claire Saldana

It is so interesting that the way we talk can show others what our identity is. The simple use of this dialect easily tells people our gender, where we are from, and our economic status. I had always heard the term fresa but I never knew the exact meaning behind it. Just by hearing the word I figured it was a girl is of a higher status or ditzy. I never would’ve thought about the speech connection. This was a very well written article and very informative.

Arturo Canchola

Hi Ana Lucia! You did an excellent job distinguishing the differences between these two well-known Spanish-speaking populations. Your article was very informative: I didn’t know where the notion of a “valley girl” accent originated! Demonstrating the parallels between the “valley girl” accent and the “fresa” accent helped me understand what a “fresa” accent consisted of. I had never heard of the phrase before until I came to St. Mary’s! I also loved that you included a reference to “Rebelde” — with the information you provided in the article, I think Mia Colucchi is a great pop-culture example of what a “fresa” sounds like.

Celeste Pérez González

Ana Lucia, what an interesting article! I had never heard of the song “Valley Girl” so it is interesting to learn and read about the connection this song has with “valley girls” and “fresas.” It is also interesting to learn about the similarities that these two terms have, for example that Valley Girls and Fresas phonologically shorten certain words.

Cassandra Cardenas-Torres

Hello I really liked your article and how you gave examples both in American and Mexican culture. Growing up in a Spanish house hold being a fresa was embarrassing and many few it as if your saying your better then them. I do think it’s interesting how even spanish speakers in Texas have different ways to say things.

Patrick

I find it all quite interesting as a juero who lived a few years going to school in Laredo. It seemed to me later when I moved to Austin that I could tell the difference between the accent from Laredo (in english) vs the accents I heard from El Paso (in english) or McAllen (in english). I didn’t know what it was, but I suspect this is it and it translates over to the way people were speaking english as well.

Ana F. Suarez

Hi Ana,

great article on comparing two social groups who are both influenced by Mexican American culture! It is a great article, and very detailed on how you even describe linguistically their pronunciation of words and phrases, also how the role of pragmatics comes into play a lot! Would be very interesting for you to continue this journey of fresas and valley girls, but now with how they connect with “juniors y hijos de papi” – young man adult version of fresas and valley girls.