“I looked, and there before me was a pale horse! Its rider was named Death, and Hades was following close behind him. They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine, and pestilence, and by the wild beasts of the earth.” (Revelations 6:8)

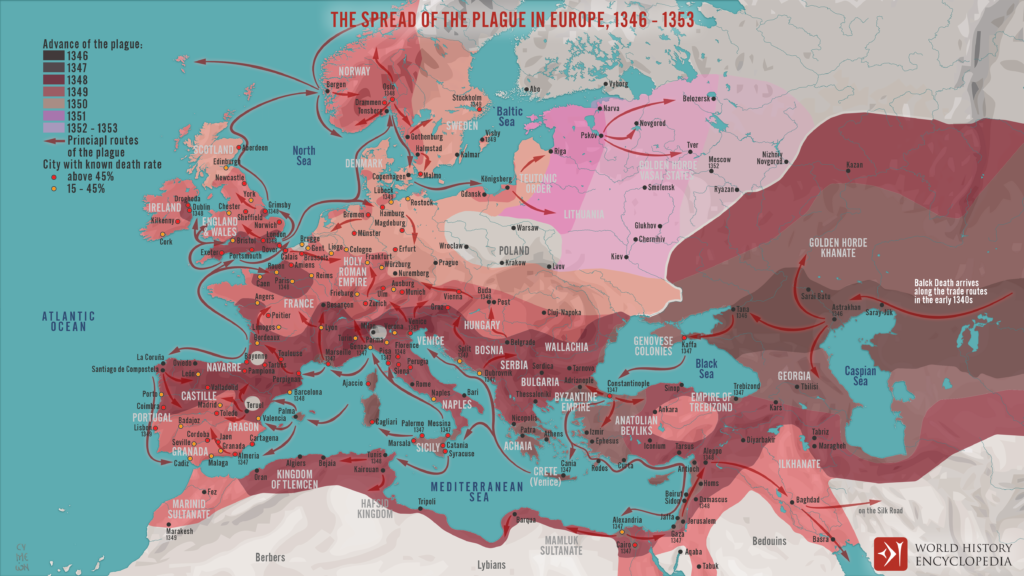

By the late Middle Ages, Europe was no stranger to warfare, famine, and disease. The French and English were fighting on the fields of Normandy. From 1315, there was a massive famine that weakened and starved Europe. And, as with many great upheavals, the Black Death entered Europe by way of a violent incitement. The city of Kaffa, today known as Feodosiya, sits on the southern coast of Crimea, east of modern Sevastopol; in the 1340s, the city was a colony of the Republic of Genoa, who had purchased the city from the Mongol Empire. The Genoese, the people of an Italian city-state located in the northwest of the Italian peninsula, had a number of colonies around the Black Sea, and bought the city of Kaffa in 1266, and in the time since, they had built up what was once a small village into a magnificent city, with bustling harbors filled with hundreds of ships, inhabited by upwards of 70,000 people. Unfortunately for the city and its inhabitants, however, the same interconnectedness that had enabled the trade that made Kaffa great, would also enable its decimation.1

By 1343, war erupted between the Mongols and the Genoese; by 1347, the city of Kaffa was under siege. To the detriment of the Mongolian force present at the siege, their ranks began to be decimated by a mysterious illness; this disease would cause large swellings on the groin and joints, with a fever; days later, the infected would die. Faced with the destruction of their army due to this horrific sickness, the Mongols opted to perform what has been documented as one of the first accounts of biological warfare in human history; they catapulted the infected corpses from their encampment over the walls of Kaffa, in an effort to infect the Genoese with the sickness that ravaged their own ranks. It worked, and the Genoese in the city soon began dying off as a result of disease. 2 By the end of the siege in the spring of 1347, life in the city was in a hellish state; bodies stacked akin to firewood, swarms of rats and other scavengers, and worst of all, only two ways to escape: death, or the sea. A fleet of Genoese galleys, filled with passengers of both human and beast, departed from the besieged city of Kaffa, bound for European ports. Unbeknownst to the sailors of these ships, they carried with them the harbingers of what would eventually become known as the deadliest pandemic in human history. They spread this apocalyptic illness through to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, the lynchpin through which all ships moving from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean had to pass. The galleys made their stop there, but were expelled due to the illness the sailors were afflicted with. Regardless, the Black Death had already been established in the city, and the ships pressed onward, toward other destinations throughout the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.3

In October of 1347, a dozen of these Genoese galleys arrived in the port of Messina, in Sicily.4 Soon after, more of these galleys would arrive at other ports across the Mediterranean, such as Venice, Genoa, and Marseille.

The Pale Horse had arrived in Europe.

___________________________________________________

In this apocalypse, there has been established the sword, the famine, and the pestilence; but what of the wild beasts of the earth?

In the case of the Black Death, the beasts that spread the pestilence were not particularly worthy of being titled beasts; the harbinger of the disease that wrought so much death was the humble rodent. The disease that caused the Black Death is a bacteria known commonly as “plague,” or back then, “pestilence” as well, and now formally known as Yersinia Pestis, after the man who first identified the disease in 1894, Alexandre Yersin.5

Yersinia Pestis likely evolved in Central Asia, where it is endemic within populations of rodents, such as marmots, prairie dogs, and rats; however, the primary method of transfer between these rodents (and later, other species) is by fleas. Fleas carry the plague bacterium within their digestive system, and when biting an unsuspecting host to feed, as it normally would, the bacterium is introduced into the body of the flea’s host, where the bacterium normally spreads to the lymph nodes and then to the rest of the body. However, rat fleas (and likely human fleas as well) are not the only way that the plague can spread; in some cases, the plague can spread to and manifest in the lungs, causing both a new set of symptoms as well as adding a new dimension to the danger posed by the disease: a disease such as the plague, spreading airborne, adds a new level of contagiousness to an already lethal illness, as it can spread from creature to creature with no intermediary. In addition, the disease can enter through open wounds, which was likely common at Kaffa.6

Fortunately, until the late Middle Ages, the plague was effectively contained within the Central Asian pocket that it originated from. That is, however, until a handful of factors came together to provide a perfect storm: trade routes, famine, and the weather. Changing wind patterns and a global cooling would’ve pushed both marmots and Mongolian herders into closer contact, the fleas transmitting plague to them; once infected, the Mongolian herders would’ve spread the disease to merchants traveling along expansive Mongolian trade routes; spreading to China, or making its way across the Russian plains, eventually arriving at Kaffa, from whence it spread to the rest of Europe.7

A world away, these same weather patterns and cooling that were driving the Mongolians and marmots into closer contact, brought torrential rainfall all across Europe. In 1315, these weather patterns caused a massive crop failure that drove millions of Europeans to starvation, and even to cannibalism.8 This famine, known as the Great Famine of 1315, lasted for seven years, before the weather finally returned to normal, in 1322, leaving millions of people dead in its wake, signaling a firm end to the impressive growth Europe had achieved in the early Middle Ages. Those that survived would go on to have weakened immune systems, especially the children; children living during the Great Famine would especially be weakened by the lack of nutrition, and would be adults by the time of the Black Death’s arrival in Europe.9

Such a wide conglomeration of smaller, separate events had set the stage for Yersinia Pestis to sweep through Europe with a morbid efficiency hardly seen before or since.

___________________________________________________

Your family is dead. Your friends are dead. In your town, the church bells have been ringing constantly, signifying the constant death that you see all around you. At the church, dead bodies are dumped into massive pits; there is no formality and little funeral proceedings, if any at all. Throughout the town, the dead and dying lay in the streets, in their homes. You know that there will be no escape from this pestilence; the world is ending.

The Autumn of 1347 was a brutish and terrible one for Messina, ground zero of the Black Death’s arrival in Europe. The dying off began almost immediately after the Genoese ships docked, as the town’s inhabitants began to fall sick with strange symptoms; the first of these would often be mild, and similar to the effects of other sicknesses: a fever, nausea, and vomiting. However, after a day or two, large swellings would form, on the groin, under the arms, or somewhere on the neck; these swellings, known as buboes, ranged in size from that of a nut to an egg to a fruit, and they were extremely painful to the touch; for days the unfortunate victim would cough up blood, and vomit constantly. Death followed within a handful of days after one fell ill. Anybody who had any sort of contact with the infected was sure to take ill and die a painful death.10

Something perhaps worse than a painful death such as was caused by the Black Death, is a painful death, alone. Such rapid and horrible manners of death that occurred spurred paranoia among those who were healthy, who, in a desperate attempt to stay alive, cut off anyone they knew who became infected. Parents abandoned their adult children; spouses abandoned each other; friends and neighbors, once close, viewed each other as little more than a walking death sentence, if one even gazed at them, leaving many victims of the plague to suffer and die bedridden in their own blood-stained clothes and terrible swellings, no one left to care for them. Part of this extreme reaction was the manner in which the Black Death came; like a deathly cavalryman, the Black Death swept across through towns, killing everything in its wake; families, friends, entire villages; naturally, this prompted entire towns to empty out and their inhabitants to flee to the countryside.11

By the winter of 1347-1348, the Black Death had carved a path through central Italy, and had also landed in Venice and Genoa; the two great rival city-states of Italy, both decimated by the Pale Horse. In Spring, it had arrived in Florence; and this mass flight of people from the cities would provide the backdrop for one of Italy’s most influential pieces of literature: Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron. The story details a group of ten people, seven women and three men, who flee the city of Florence for the Italian countryside, seeing nothing left in the city for them but death. While hiding out at a remote villa, they take turns telling allegorical stories. Boccaccio opens his work with a morbid description of the Black Death:

“For practically from the start of spring in the year we mentioned above [1348], the plague began producing its sad effects in a terrifying and extrodinary manner. It did not operate as it had done in the East, where if anyone bled through the nose, it was a clear sign of inevitable death. Instead, in its onset, in men and women alike, certain swellings would develop in the groin or under the armpits, some of which would grow like an ordinary apple and others like an egg, some larger and some smaller. The common people called them gavoccioli, and within a brief space of time, these deadly, so-called gavoccioli would begin to spread from the two areas already mentioned and would appear at random over the rest of the body. Then, the symptoms of the disease began to change, and many people discovered black or livid blotches on their arms, thighs, and every other part of their bodies, sometimes large and widely scattered, at other times tiny and close together. For whoever contracted them, these spots were a most certain sign of impending death, just as the gavoccioli had been earlier and still continued to be.”12

The Decameron is a fascinating insight into the psyche of the inhabitants of Florence as their world was collapsing around them. Boccaccio recounts much the same scenario as was present in Sicily and Venice and Genoa; so many people were dying such horrible deaths, so fast, that those who were well did their best to avoid any sort of contact with anyone who was sick. Besides family members abandoning each other, the structure of society had begun to break down within many of the cities struck by the pestilence. Some people fell under the belief that should they live modestly, then they would be spared the clutches of the pestilence. Others believed in a sort of middle ground, living to satisfy themselves to a modest amount, but still having freedom to live comfortably. And still others believed that they should take hedonism to the extreme, and indulge themselves in carnal and earthly desires, such as food, wine, and other pleasures commonly considered to be vices.13

And why wouldn’t they? After all, they were living in what many believed to be the end of the world.

The effects of the Black Death in Florence and other locations in Italy are some of the best-documented instances of the Black Death, likely in part because Italy was one of the first regions in Europe to succumb to the plague.

Giovanni Villani was another Florentine writer who chronicled the horrible ravages of the Black Death. His chronicle takes care to describe the origins of the plague, and its effects on the city of Florence; and for him, the Black Death never ended, as his chronicle reads, “And this pestilence lasted until _____, and many areas of the city and in the provinces remained desolate.”14 Villani died of the pestilence that he wrote of before he could finish his chronicle.15

While the Black Death was jumping from town to town along the Italian peninsula, it was making its way through France as well. The pestilence had come to France much the same way it had to Sicily; through Genoese ships that were docked in the port of Marseille just long enough for the sickness to have established a foothold in the city, on November 1st. From there it spread to Avignon, the residence of the Pope and seat of the Papacy. Despite the prayers and whatever holy protection that may have come, the pattern repeated here, as it had everywhere else, and the Pale Horse cleaved through the city with an unholy sword. Bonfires were lit in the city in an effort to stave off the plague; graves were filled and bodies stacked. Pope Clement VI, the Pope at the time, consecrated the entirety of the river Rhone so that bodies were able to be laid to rest there in compliance with the rules of a Christian burial. By Spring, the corpses of those felled by the pestilence choked the river.16 And so it was; everywhere the pestilence went, death followed.

___________________________________________________

One of the more terrifying aspects of the Black Death was the manner in which it swept through Europe; it seemed to quite literally “jump” from town to town, unpredictably; where one town may be spared for a month or two, and neighboring towns decimated, the plague would then circle back around and depopulate the town that was previously unscathed. Today, the method with which the plague was spread is known as a “metastatic leap,” and it was achieved primarily by vectors of infection traveling aboard ships, or horse and carts.17

Also affecting the speed at which the disease spread were the three “types” of plague that one could develop based on where the bacterium spread within the body.

Plague manifests itself in three forms; bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. Bubonic plague is the most common form of the plague, being spread by flea bits, and its main characteristic was the previously described swellings, known as buboes, which usually form to the closest lymph node to where a plague-infected flea bit its human host. Mortality from the bubonic form of the plague ranges around 60%, without modern antibiotic treatment, and death follows 3-5 days after infection. Pneumonic plague is less common in the modern era, but seemed to be far more common during the Black Death outbreak, especially in winter. This form of the plague sees the bacterium enter the lungs by one of two ways: either the bacterium enters the lungs directly, by an individual breathing in droplets coughed up by someone else, or the bacterium spreads from the lymphatic system to the lungs; this second form of pneumonic plague being known as “secondary pneumonic plague,” as it developed as a result of a bubonic plague infection. Regardless, the ability for such a virulent disease to spread from person to person without the mediation of fleas from rodents holds great importance; direct spread results in a much faster method of infection, especially in cities, than would be expected had the Black Death been solely spread by fleas. Mortality for the pneumonic plague sits at around 95% to 100% without treatment by antibiotics. Furthermore, with this form, antibiotics must be utilized within the first 24 hours of symptoms appearing for a chance at survival. Septicemic plague is the least common manifestation of the plague, and results from plague bacterium moving into the bloodstream; from there, it rapidly moves to the major organs of the body, causing an extremely rapid death, so much so that buboes or other symptoms cannot appear fast enough. Mortality for septicemic plague occurs within 15 hours, on average. Without modern antibiotics, mortality occurs in 100% of septicemic instances.18

___________________________________________________

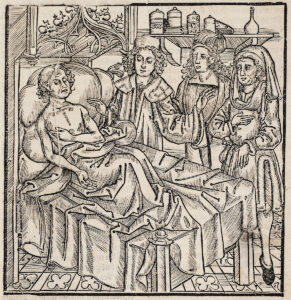

When confronted with a disease, it is the duty of the medically trained within the affected area to attempt to find a cure or treatment for the disease, and the Black Death was no different. One emerging theory that was floated among medical scholars at the time was that such a universal disease as the Black Death was caused by poisons that contaminated the air, especially by Gentile da Foligno, a doctor from Perugia, an Italian city. Foligno himself was slain by the plague in June of 1848, having spent the previous months tending to the sick and dying.19

However, many doctors from the period realized that there was little use or recourse to alleviating the plague once it had infected an individual, and so it was preferable to prevent contraction of the sickness in the first place; in accordance with the poison theory of disease at the time, the main way of avoiding poisoned air was to escape poisoned air. Therefore, most doctors of the time suggested that flight from the city would be the best course of action, for those who could afford to do so, and this advice certainly contributed to the widespread abandonment of friends and family mentioned above.20

Alternatively, when flight was not an option, “evacuation” of hostile poisons within the body was prescribed; this included such methods as bloodletting and substances that would induce vomiting, or laxatives as well. Another method that was tried was to target the buboes that had formed on a patient; this procedure involved cutting open and draining the buboes, an extremely painful process as these buboes were already painful to the touch.21

While medicine failed to stop the plague, inhabitants of cities were faced with the reality of their situation; cities before the Black Death were already unfathomably filthy, with refuse running down the streets, and sanitation being effectively nonexistent (something which certainly aided the Black Death in becoming so prevalent), and the pestilence killing off so many within such a short time only compounded urban woes.22 Pistoia set up a series of ordinances preventing any bodies from coming into the city from the outside, whether in a coffin or not, and prohibited tanning of leather and certain butchering practices within the city’s limits.23 In Venice, a committee was appointed to coordinate the response to the Black Death; by the summer, the city banned mourning clothes, as the citizens of the city draped in black bode ill for the future of the city; in Florence, it was similar, as the city banned the ringing of church bells at funerals in an effort to raise the spirits of those who remained alive in the city. What was left was a silence that spoke louder than any church bell could.24

In a similar vein to the banning of mourning clothes, cemeteries quickly filled within the cities that were struck by the pestilence; as a result, the “plague pit” was born. Boccaccio wrote:

“There was not enough consecrated ground to bury the enormous number of corpses that were being brought to every church every day at almost every hour, especially if they were going to continue the ancient custom of giving each one its own plot. So, when all the graves were full, enormous trenches were dug in the cemeteries of the churches, into which the new arrivals were put by the hundreds, stowed layer upon layer like merchandise in ships, each one covered with a little earth, until the top of the trench was reached.”25

Agnolo di Tura, a chronicler from Siena, describes these pits further:

“In many parts of Siena, very wide trenches were made and in these, they placed the bodies, throwing them in and covering them with but a little dirt. After that they put in the same trench many other bodies and covered them also with earth and so they laid them layer upon layer, until the trench was full. Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could without a priest, without divine offices. Some of the dead were… so ill covered that the dogs dragged them forth and devoured many bodies throughout the city.”26

Unsatisfied with these arrangements, Agnolo di Tura proceeded to dig a separate grave, and he buried his wife and five children with his own hands. In London, it was much the same; on days when fewer dead were brought in, more care was taken to ensure at least some semblance of a proper burial and funeral, but regardless of how many died, they were arranged orderly, with their heads to the west and feet facing east.27 Even amidst one of the greatest tragedies in human history, human civilization managed to scrape by, if just barely.

___________________________________________________

From France, the plague spread further to modern-day Germany, and from there, it spread to Eastern Europe; the Pale Horse galloped from England to Scandinavia, and from where it spread across the Baltic to Russia. By 1352, the pestilence had reached Moscow, the final stop in its apocalyptic warpath.

In its wake, the Black Death had left anywhere between a third to half of Europe’s population dead. John Aberth, a Medieval historian from Cambridge University, writes of his new take on the mortality rates of the Black Death:

“In 2004, the Norwegian demographer and historian Ole Benedictow argued for an overall mortality percentage for the Black Death of 1347-53 of 60 percent, based on his demographic survey of Spain, Italy, France, Belgium, and England. This was essentially a doubling of the one-third rule, and the highest figure yet advanced by any scholar. Our own demographic survey favors a slightly more conservative, 51-58 percent mortality for all of Europe. Perhaps now there should be a new, “one-half” rule for the first outbreak of plague.”28

While the death toll in many cities in Europe, such as in Avignon, Venice, Florence, Siena, Messina, and London, numbered around 50% of the population, the Black Death was not limited to cities during its reign of terror; rural areas could arguably have been in more danger than the urban areas, due to a higher ratio of rats living in proximity to humans because of the lower human population density.29 After the pestilence had burned itself out, a great many villages had been abandoned outright due to the sheer amount of death that took place; in England, many of the rural villages were never repopulated after the Black Death swept through them. While the plague had stopped, the rate of births had also slowed, and these villages were simply never able to replace those they lost (due to a number of factors even after the Black Death), in the centuries that followed, and they fell into disrepair and abandonment.30

Henry Knighton, an English chronicler, wrote of this decline:

“After the aforesaid pestilence, many buildings of all sizes in every city fell into total ruin for want of inhabitants. Likewise, many villages and hamlets were deserted, with no house remaining in them, because everyone who had lived there was dead, and indeed many of these villages were never inhabited again.”31

Unfortunately, the plague would regularly occur in epidemic phases in Europe for the next centuries, until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, carrying off millions more in the process. However, out of the apocalypse came some of the very basics with which a decimated Europe could reforge itself.

___________________________________________________

With the massive depopulation caused by the Black Death, the peasantry found themselves in possession of more power than they had ever known previously. Such a shortage of labor across all disciplines meant that a worker could, if he found his current employment situation to his disliking, leave and seek employment at another location; and he would find it too. Another related outcome of the Black Death was a massive increase in the amount of available land; while before the Black Death, Europe faced a land problem, with more and more land being farmed for diminishing returns. After so much death had been wrought, a peasant farmer could choose which land he wished to farm, a sign that serfdom was at last beginning to take its last breaths. Such depopulation also spurred along technological development, and the concentration of wealth in a smaller segment of the population set the stage for the birth of the middle class. The health responses in Venice and elsewhere had become the foundations for a modern system of healthcare.32 Although it would take centuries, the Black Death, through its terrible reign as the Pale Horse of the apocalypse, had, ironically enough, laid the groundwork necessary for society to develop and advance past such a horrific event; humanity had passed through a storm of pestilence, and now they could rebuild.

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 1-6. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 14-15. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 8-10. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 83. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 41-42. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 18-20, 34-37; John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 2-7. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 38-39. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 60. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 58-64. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 84-85. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 85-86; John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 197-204. ↵

- Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron (Santa Fe: El Cid Editor, 2003), 5-6. ↵

- Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron (Santa Fe: El Cid Editor, 2003), 6-8; John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 106-111. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents, Second edition, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2017), 26-27. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents, Second edition, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2017), 26. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents, Second edition, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2017), 59-62; John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 149-153. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 20-27. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 5-7; John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 20-23. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 61-65; John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents, Second edition, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2017), 48-51. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 71-74. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 72-79. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 64-71. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents, Second edition, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2017), 141-143. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 93-94, 110. ↵

- Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron (Santa Fe: El Cid Editor, 2003), 11. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 118-119. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 213-214. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 36-37. ↵

- John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 16-17. ↵

- Colin Platt, King Death: The Black Death and Its Aftermath in Late-Medieval England (Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 33-45; John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 282-283; Norman F. Cantor, In the Wake of the Plague : The Black Death and the World It Made (Riverside: Simon & Schuster, 2014), 85-87. ↵

- Colin Platt, King Death: The Black Death and Its Aftermath in Late-Medieval England (Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 5-6. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 217-224; John Aberth, The Black Death : A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (Bedford/St. Martin’s Macmillan Learning, 2016), 285-294. ↵

4 comments

Mariana Chamorro

Joseph, your publication on the Black Death is awesome! Your storytelling skills are amazing, making the events feel real and impactful. Plus, you break down complex historical details in a way that’s easy to understand and enjoy. Keep up the fantastic work, and I can’t wait to read more from you!

LEE

I like this article that you wrote. It is very interesting story. The effect of black death is always scary for people all around the world. It is a disaster that can kill many people. I really like your article and appreciate for nice article. Thank you for writing this down and have a good day. I will always read this kind of article.

Dr. Meghann Peace, Ph.D.

Congratulations on your article and your awards, Joseph! This is phenomenally written and an excellent in-depth look at one of the most tragic times in human history. One of my favorite books – Doomsday Book – is a sci-fi take on the Black Death in England. It’s beautifully written (much like your article), and I recommend it!

Andrew Ramon

Joseph, this was such an in depth article, I really enjoyed your work. I didn’t know the origins of the black plague and this enlightened me. It is wild how the mongols used corpses as weapons of chemical warfare for a siege, ingenious, but cruel. I appreciate all the work that you have put into this research piece, excellent job.